Using Picturebooks to Promote Home Literacy and Social Emotional Learning

Eun Hye Son and YuWen Chen

During the COVID-19 pandemic, schools and public libraries were shut down for the safety of social distancing, which changed the dynamics and platforms of children’s learning. Many young elementary students struggled to concentrate on virtual learning, and the lack of physical interaction delayed students’ social emotional development (Watts & Pattnaik, 2023). Moreover, distance education has risen to the challenge of students’ social literacy, which is “a critical component in the elementary classroom, helping children to interact and communicate effectively during class activities” (Alsubaie, 2022, p. 2). With these burning issues in mind, we, as mothers and researchers, became concerned about children’s literacy development and social interactions in such a challenging time. After researching through extensive scholarly articles, educational news, and other educational forums, we found home literacy practices as a way to engage children and parents/caregivers in literacy activities related to live experiences (Chamberlain et al., 2020). Keeping in mind that not all parents/caregivers have the confidence required to lead their children in the practice of literacy at home (Steiner et al., 2022), we wanted to share our experiences to help them understand how to foster children’s social literacy skills and social emotional learning at home.

To start, we created a home-based literacy community based on the concept of a home literacy environment (HLE), which refers to “a wide range of home activities and experiences that promote literacy development” for children (Van Tonder et al., 2019, p. 87). HLE involves family literacy practices whereby parents/caregivers do shared readings and use dialogic reading strategies, ask and respond to open-ended questions related to events read about in the books, or do writing activities (Read et al., 2022). Our home-based literacy environment was formed in the summer of 2021 by inviting six elementary students (Dino, Greninja, Nya, Cutie Bear, Hana, and Aliyah) ranging from kindergarten to 2nd grade, to be part of this learning community at either the researcher’s or children’s home.

To plan a curriculum for the home-based literacy community, we selected picturebooks that highlight differences and similarities among people, various elements of different lifestyles and cultures, and acts of inclusion. Considering children’s ages and grade levels (ages 5–8), we chose books that contained clear and engaging storylines with the appropriate vocabulary for them to read and relate to. After reading the books aloud with children, we encouraged them to reflect on the differences and similarities that they had come across in their own lives. In doing so, they learned to demonstrate respect and appreciation for the range of cultures and diverse people through guided discussion questions (i.e., What was your favorite part of the story? What did you learn from the characters and their experiences? What connections such as text-to-text, text-to-self, text-to-world did you make?) and literacy activities (i.e., writing, drawing, pair or group work, discussions, and presentations).

In this article, we discuss how we designed this project and facilitated children’s participation in the home-based literacy community, based on the following three themes: recognizing our similarities and differences, learning about various elements of different cultures, and embracing diversity for inclusion and social emotional learning.

Recognizing Our Similarities and Differences

We believe that recognizing people’s similarities and differences is a gateway to understanding who we are, which is the foundation of social emotional development. We presented two picturebooks to help children become more aware of the similarities people share in addition to their differences. Whoever You Are (Fox, 1997) shows that people around the world have similarities inside even though they might look different on the outside. Despite differences in schooling, language, lifestyle, and physical appearance, they share common emotions and feelings. Next, we read aloud Same, Same but Different (Kostecki-Shaw, 2011), which portrays two boys, one living in the United States and one in India. The boys share similar life experiences and interests, including schooling and outdoor activities, but these occur in different ways.

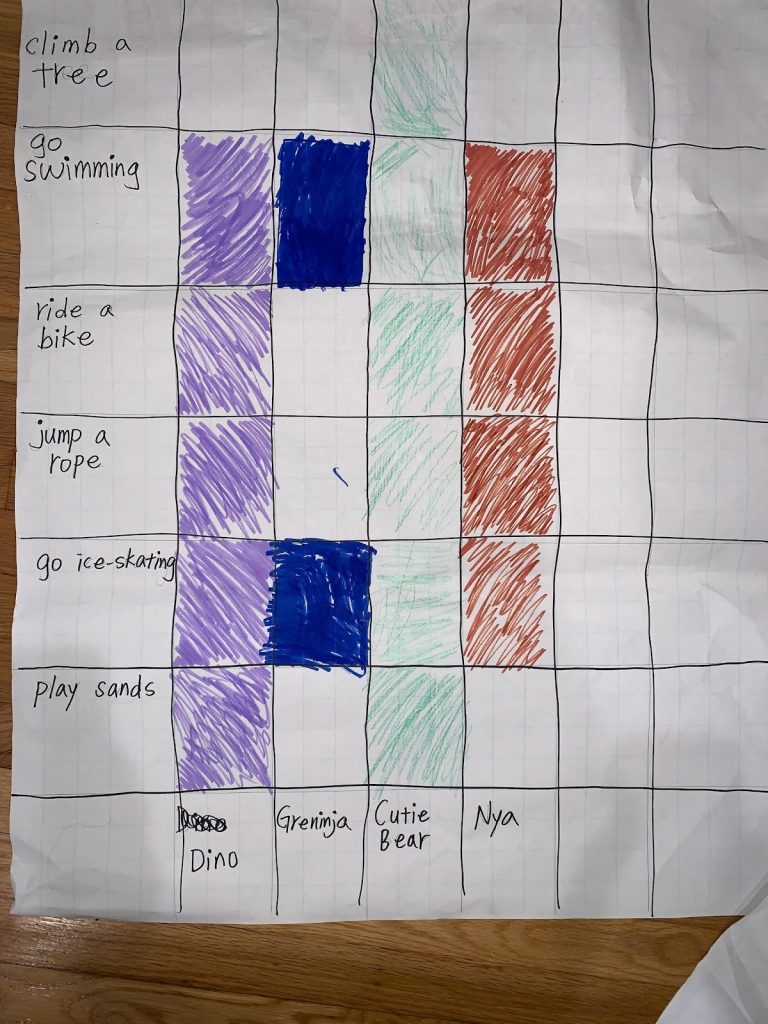

After reading this book, we provided an activity to help children think about their personal preferences and to discover similarities and differences with others. We surveyed their preferences of outdoor activities and invited them to color the activities they like on a poster graph (see Figure 1). During this activity, children were excited to learn about their peers’ preferences of outdoor activities. Instead of using their real names on the poster graph, they decided to use their favorite animation characters (Nya and Greninja) and stuffed animals (Dino and Cutie Bear) to represent who they are in this particular activity. Nya was surprised by Dino’s choice, exclaiming, “You like playing in the sand! I thought you like climbing trees.” Greninja was able to summarize their commonalities, “Wow, all of us like swimming and ice-skating. Perhaps we can go swimming and ice-skating together.” Finding shared interests allowed children to connect with one another. As they sometimes realized that their assumptions on their peers’ preferences of outdoor activities were wrong, they were able to further deepen their friendships in this lively community environment. During the COVID-19 pandemic, public facilities, such as ice-skating rink and swimming pools, were temporarily closed. Finding that their interests connected them, they became excited about what other potential outdoor activities they could explore together once the pandemic was over. This provided them with hope to sustain their social emotional well-being during such a challenging time.

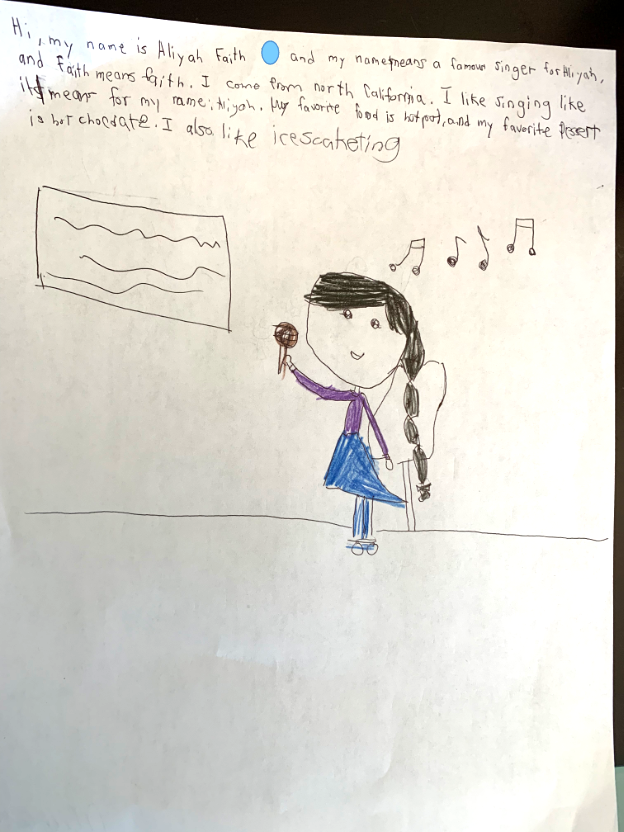

We also brought magazines, catalogs, store flyers that included playgrounds, toys, food, animals, nature, etc. and asked children to cut out items they like. Then, we asked them to pair up with a partner to share with each other why they like the items they chose by comparing and contrasting their preferences. After that, they completed a Venn diagram by gluing down the items they had cut out. When Cutie Bear and Nya were collaborating on the sameness of their preferences, they enthusiastically asked each other questions in order to complete the task. Nya asked, “Do you like shrimps?” Cutie Bear responded, “Yes! I love shrimps! They taste so good.” Nya, “Yes! Shrimp is also good for our body.” Cutie Bear added, “Cherries are good too!” Nya joyfully nodded in agreement. This activity not only increased children’s awareness of their own preferences, but also gave them an opportunity to help them find commonalities with their fellow classmates (see Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Cutie Bear is cutting the food he likes from grocery store flyers, putting them on a plate before discussing with his partner.

Learning about Various Cultural Elements People Have

Recognizing their similarities and differences not only helps children understand their own individuality and identity but also lays a foundation of learning about the various cultural backgrounds of people. First, we encouraged children to learn more about their family because that is one of the initial places for them to develop their identity and to shape who they are. We shared the following two books, Where Are You From? (Méndez, 2019) and Alma and How She Got Her Name (Martinez-Neal, 2018). The main characters in the two books have questions about who they are. In response, their family members (i.e., abuelo and dad, respectively) tell them stories about their origins and their names.

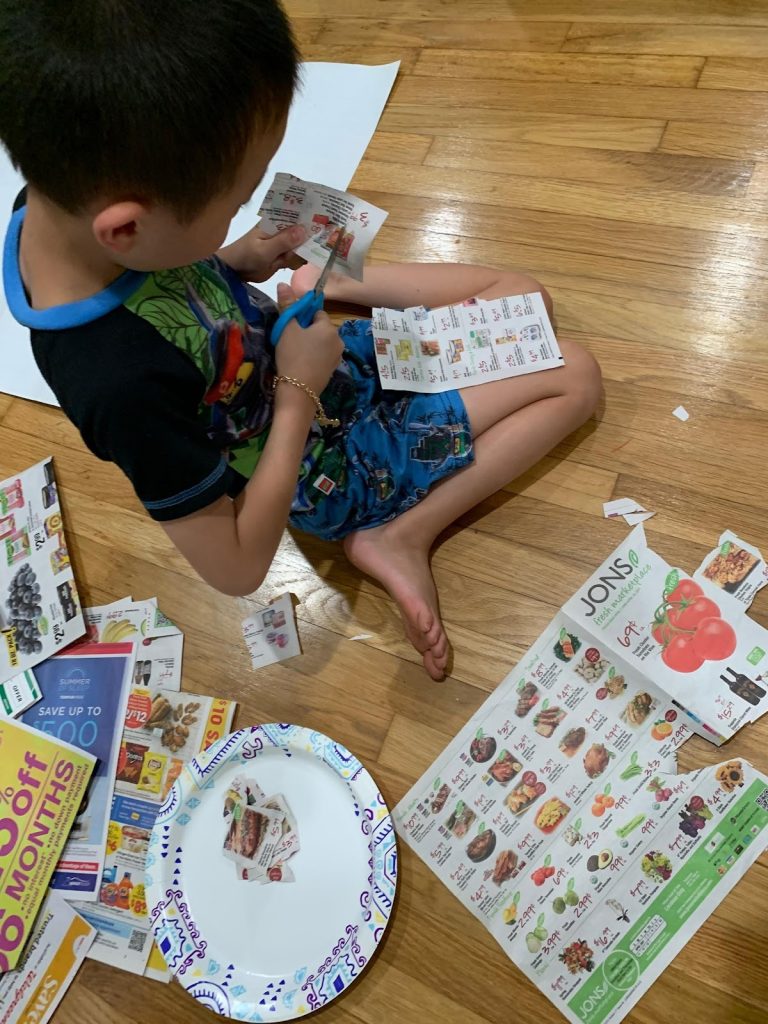

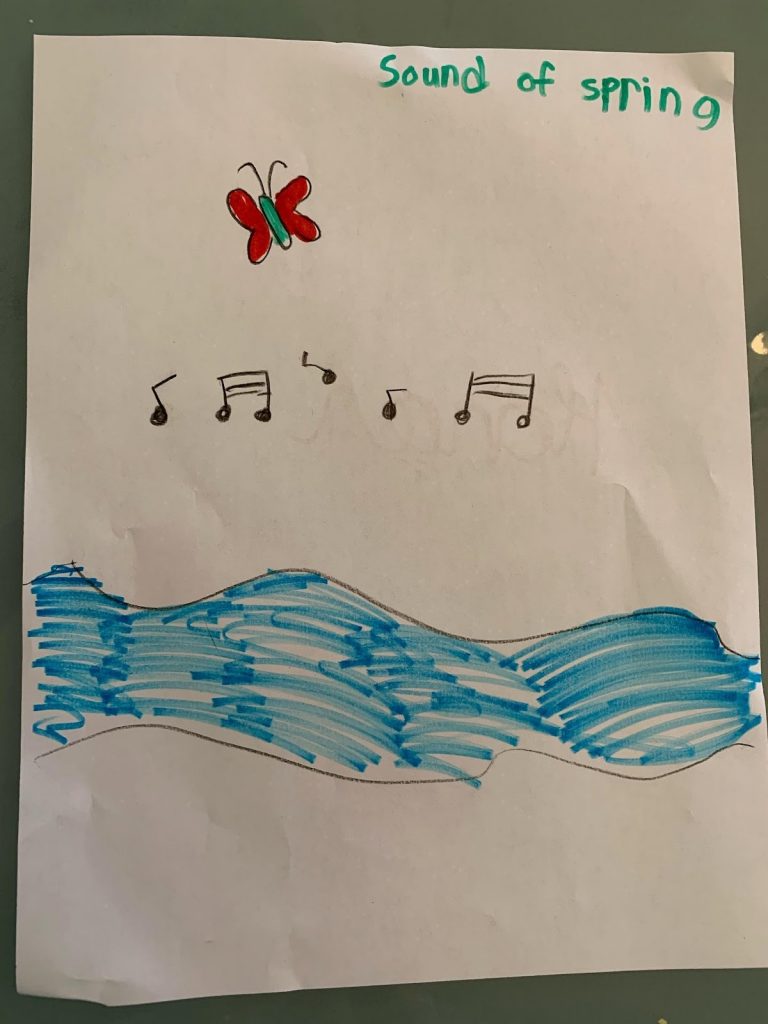

After sharing these books, we asked children to reflect on themselves and to come up with lists of where they are from using sentence frames, i.e., I am from _____ (place, family, tradition, everyday items, memory, food, etc.). Afterwards, we asked them how they spent their leisure time with their family. This inquiry helps children elaborate more on why they selected the words, sharing stories about their family cultures. Then, we asked them to share the meaning of their names and interests in either free drawing or writing to help them genuinely reflect on who they are and understand the name given by parents/caregivers. Hana, an American-born Japanese child, explained her name: Hana (はな) means flower in Japanese. She said, “My parents gave me this name. I was born in the spring season. Flowers bloom in the spring.” When she shared her drawing, she explained her name is like a delightful melody flowing in the river in the spring. She drew a butterfly that enjoyed the beautiful sound by joyfully flying near the river. Hana named her drawing “Sound of Spring” (see Figure 4A). Another child, Aliyah, a second-generation, American-born Taiwanese, said that her father likes a singer named Aaliyah, so she was named after her. Aliyah shared that she actually likes singing like the singer Aaliyah. Her middle name is Faith because her parents hope she has faith in life. She further elaborated on the foods she likes and the sports she likes to do (see Figure 4B). These activities open the door for children to understand an array of family stories and cultures that shaped and influenced who they are.

Figure 4. Children’s artifacts showing who they are: Hana’s drawing, “Sound of Spring,” reveals the story behind her name (A).

Embracing Diversity for Inclusion and Social Emotional Learning

We believe greetings are a good initial topic to make the abstract concept of culture more concrete and relatable when teaching children how to respect and embrace differences to foster social emotional learning. Say Hello! (Isadora, 2010) is a great book to introduce young readers to different languages. As Carmelita, the main character, walks through her neighborhood and encounters her culturally diverse neighbors, she exchanges hellos in their respective heritage languages. We used this book to talk about how different cultures have different languages to convey the same meaning, and we encouraged children to learn to say hello in different languages. Additionally, we talked about how people coming from different countries make different gestures when greeting each other such as air kisses on the cheek, handshakes, bow, etc. To practice greetings of different countries, each child randomly drew a flashcard of a national flag and then led everyone in practice of that country’s greeting word with a particular gesture. If children forgot how to make a particular greeting gesture and the greeting itself, they could just smile. This helped children become aware that nonverbal facial expression, smiling at people, is also a kind way to greet others when people do not know how to act and say greeting words appropriately.

To extend the discussion of greetings and gestures, we introduced a humorous picturebook, How Do You Hug a Porcupine? (Isop, 2011). It provided a great starting point for the children to open up a conversation about understanding differences. This book has a repeated question-and-answer structure: The question, “Can you hug {insert specific animal here}?” is followed by the answer how to hug different animals in appropriate ways. We used this question–How do you hug a porcupine?–multiple times throughout the story to facilitate a discussion on finding solutions to hug a porcupine without getting hurt based on other appropriate ways to hug different animals. We also expanded the discussion to talk about how to become friends with others whose actions and cultures differ from their own and who may seem difficult to develop a relationship. In addition, we brought up the idea that people have different ideas about physical boundaries and touch during greetings, and so we need to respect people’s comfort zones.

Researcher: How do you become friends with people who are difficult to get close to?

Cutie Bear: Maybe this person is angry about something.

Researcher: What would you do?

Cutie Bear: I will ask this person what happened and try to talk to him in a friendly way. If this person doesn’t like a hug, I definitely won’t do it. I don’t want this person to feel uncomfortable.

Researcher: Great! I agree with you, Cutie Bear! As you know, a social and physical distance policy has been introduced in public due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Cutie Bear: I see. So, if the person is not comfortable to shake hands with me or hug him when I greet him, I won’t do that. I will give him a smile.

As seen in this conversation, Cutie Bear tried to be compassionate and find a way to understand the person with whom it seems difficult to establish a relationship or who needs physical boundaries when interacting.

We also introduced realistic picturebooks that are set in schools where children are involved in daily activities and social interactions with others: The Invisible Boy (Ludwig, 2013), I’m New Here (O’Brien, 2018), and All Are Welcome (Penfold, 2018). These books tell stories about the interrelatedness of students, including those with a variety of personalities, hobbies, strengths, and linguistically and culturally diverse origins. The stories highlight how children might become more aware of fellow classmates who may need a friendly, helping hand to navigate cultural adjustments, language barriers, or social interactions. We asked children to make personal connections to the books by asking the following questions: (1) Have you ever felt fear in a new environment? How do you overcome your fear? (2) In the past, have you had any new transfer classmates in your classroom? How do you become friends with them? Children discovered that most experience fear in a new environment. This shared experience allowed them to understand the importance of having empathy and showing kindness to others. We used these books to encourage children to foster inclusive and welcoming classroom communities and to create a sense of belonging for all.

Last, we shared books focusing on intergenerational family relationships, Drawn Together (Lê, 2018) and Grandfather Counts (Cheng, 2000), portraying how American-born Asian grandchildren and Asian (Thai and Chinese) grandfathers feel frustration over language barriers, generational gaps, and differing cultural experiences. Using mediums such as drawing and counting, they bridge intergenerational gaps and language barriers and rekindle their kinship with mutual understanding and love. The beautiful illustrations help children relate to their intergenerational experiences, understand cross-cultural differences, and learn how to communicate with others with compassion. After reading the book, we asked the following questions: “How would you interact with someone who is very different from you? For example, they speak a different language from you or likes food/toys that are different from yours.” And, “Have you ever felt frustrated or mad and gotten into a fight with somebody because you did not agree with the person? If so, how did you solve the problem?”

These questions encourage children to recognize their emotions when things do not go as they expected and learn to find acceptable ways to solve their problems. Cutie Bear shared his experience of his grandmother’s visit. She does not speak English, but she knows how to make delicious dumplings. Cutie Bear excitedly said, “Grandma’s food is so good!” However, sometimes he could not understand what his grandmother was saying, and sometimes he did not know how to respond to her in Mandarin Chinese. He felt a bit frustrated but tried to use his body language to communicate with her. When it did not work, he asked his mother or father for help with interpretation. These books inspired children to recognize the barriers created by differences and to find ways to connect to diverse people despite any linguistic and cross-cultural differences.

| Theme | Book Title |

|---|---|

| Recognizing similarities and differences that we all have |

|

| Learning about various cultural elements people have |

|

| Embracing diversity for inclusion and social emotional learning |

|

Table 1. Book titles used for instruction of three themes

Conclusion

We believe that this home-based literacy community created a great space for children to learn, explore, and embrace this world and express their thoughts with confidence. During the social literacy activities, they heartily shared their opinions and stories; consequently, they learned not only about others, but they learned more about themselves. They came to love to read, but also looked forward to continuing these home-based literacy practices.

We hope that this home-based literacy community enables children, parents/caregivers, and families to find connectedness and social interaction and maintain social emotional well-being through social literacy activities (Fisher & Frey, 2020). It helped children to understand that people around the world faced the same challenge, the COVID-19 pandemic, and how people arise from the innate characteristics of kindness, compassion, and empathy to make this world a better place in the post-COVID-19 era.

References

Alsubaie, M. A. (2022). Distance education and the social literacy of elementary school students during the COVID-19. Heliyon, 8, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09811

Chamberlain, L., Lacina, J., Bintz, W. P., Jimerson, J. B., Payne, K., & Zingale, R. (2020). Literacy in lockdown: Learning and teaching during COVID‐19 school closures. Reading Teacher, 74(3), 243–253. https://doi.org./10.1002/trtr.1961

Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2020). Lessons from pandemic teaching for content area learning. Reading Teacher, 74(3), 341–345. https://doi.org./10.1002/trtr.1947

Read, K., Gaffney, G., Chen, A., & Imran, A. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on families’ home literacy practices with young children. Early Childhood Education Journal, 50(8), 1429–1438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01270-6

Steiner, L. M., Hindin, A., & Rizzuto, K. C. (2022). Developing children’s literacy learning through skillful parent-child shared book readings. Early Childhood Education Journal, 50(4), 539–553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01170-9

Van Tonder, B., Arrow, A., & Nicholson, T. (2019). Not just storybook reading: Exploring the relationship between home literacy environment and literate cultural capital among 5-year-old children as they start school. The Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 42(2), 87–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03652029

Watts, R., & Pattnaik, J. (2023). Perspectives of parents and teachers on the impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on children’s socio-emotional well-being. Early Childhood Education Journal, 51(8), 1541–1552. https://doi.org./10.1007/s10643-022-01405-3

Children’s Literature Cited

Cheng, A. (2000). Grandfather counts (A. Zheng, Illus.). Lee & Low.

Fox, M. (1997). Whoever you are (L. Staub, Illus.). Harcourt.

Isop, L. (2011). How do you hug a porcupine? (G. Milward, Illus.). Simon & Schuster.

Isadora, R. (2010). Say hello! Nancy Paulsen.

Kostecki-Shaw, J. S. (2011). Same, same but different. Henry Holt.

Lê, M. (2018). Drawn together (D. Santat, Illus.). Little, Brown Books.

Ludwig, T. (2013). The invisible boy (P. Barton, Illus.). Knopf.

Martinez-Neal, J. (2018). Alma and how she got her name. Candlewick.

Méndez, Y. (2019). Where are you from? (J. Kim, Illus.). HarperCollins.

O’Brien, A. S. (2018). I’m new here. Charlesbridge.

Penfold, A. (2018). All are welcome (S. Kaufman, Illus.). Knopf.

Eun Hye Son is an Associate Professor in the Department of Literacy, Language, and Culture at Boise State University. She teaches children’s literature and literacy instruction courses. Her research interests include critically analyzing multicultural children’s literature and using children’s literature to support children’s learning.

YuWen (Maggie) Chen, EdD, is an independent educational researcher and experienced teacher with a passion for fostering literacy and cross-cultural understanding. With a background in teaching from kindergarten to college level in Taiwan and the United States, she specializes in identity development, family literacy, and immigrant education. Through her research and community work, YuWen develops family literacy curricula to support immigrant children, promoting lifelong learning and growth mindsets.

Authors retain copyright over the vignettes published in this journal and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under the following Creative Commons License:

WOW Stories, Volume XI, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on work by Eun Hye Son and YuWen (Maggie) Chen at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/xi-1/4.

WOW stories: connections from the classroom

ISSN 2577-0551