Displaying Heritage Knowledge in a Korean-English Family Literacy Exploration

Jongsun Wee and Denise Dávila

What is the potential of bookplay activities for young Korean American children and their families? This article discusses the outcomes of bookplay activities within the context of a secular intergenerational biliteracy storytime program for newcomer and first- and second-generation Korean American families in a major city of the U.S. southwest. Our program was inspired by the family storytime work of Dávila and colleagues (2017; 2022a; 2022b) in which young children mobilized their linguistic and transcultural knowledge during mealtime-related bookplay activities.

The objective of our family program was to foster young Korean American children’s learning and maintenance of their heritage language and culture. Although we worked in consultation and collaboration with families at a Korean church, the program was entirely secular and was not associated with any forms of religious education. As a community, the families were interested in opportunities for their children to listen to Korean stories and language. They wanted to spend time together, reading about and talking about their homeland, Korea, and Korean culture. In turn, we facilitated seven bilingual sessions on Sunday during the lunch hour. This article focuses on two of the sessions in which families responded to picturebooks by Korean Americans about Korean food and mealtime rituals.

Background: A Glimpse into Bilingual Family Programs

Bilingual family literacy initiatives are not universal. Varying formats and settings reflect different objectives. For example, in Hirst et al.’s (2010) study, teachers visited bilingual families’ homes and provided resources for them to support their young children’s literacy learning at home. Zhang et al. (2010) conducted a study in three different community centers with the objective of documenting changes in families’ literacy activities through their bilingual family literacy program. Dávila and her colleagues (2017) fostered linguistically- and culturally-inclusive literacy experiences for Spanish-speaking families within the space of an English-dominant public library. In Louie and Davis-Welton’s (2016) study, elementary school teachers and teacher-candidates partnered with families and community members to implement a bilingual picture book project to produce “student-authored and student-illustrated bilingual picturebooks in the classroom setting” (p.598-599).

Across family literacy studies, findings reflect common outcomes. First, no matter the venue, the project benefited families by promoting children’s biliteracy development in their heritage language and English (Hirst et al., 2010; Louie & Davis-Welton, 2016; Zhang et al., 2010). Second, the family’s heritage language and culture were valued and respected, and as a result, facilitators increased their understanding of bilingual families’ culture while developing relationships with them (Hirst et al., 2010; Louie & Davis-Welton, 2016). Third, families’ funds of knowledge functioned as valuable resources since culturally familiar content was highlighted (Louie & Davis-Welton, 2016). Fourth, families expressed a sense of belonging to the new school or new country (Dávila et al., 2017). Finally, families enjoyed the programs as indicated by high participation rates (e.g., Zhang et al., 2010), which can be challenging due to “issues such as transportation and babysitting” and parents’ ability to attend after long work hours (Timmons, 2008, p. 99).

Creating a Korean American Storytime Program

Our creation of the Korean American Storytime Program was a collaborative, community-based effort. At the time, Jongsun was a faculty member at a midwestern university. Denise was a faculty member at a local university and sponsored Jongsun’s research visit to the southwest. Denise engaged the generosity of colleagues and community members to establish the program at a local Korean church. Together, we met with church leaders and parents to discuss the project. We learned that as members of a diasporic Korean American community, church families were concerned about cultivating and maintaining their children’s emergent bilingual and bicultural Korean identities. For this reason, many of the children attended heritage culture classes at the church.

Augmenting the heritage culture classes, we developed our program to provide a third space in which families’ linguistic and cultural identities are fluid (Bhabha, 2004). According to Bhabha (2004), when diverse cultures or identities collide, there is a space where no one particular culture or identity is clearly linked. This is called a third space, and it exists in-between. The third space offers an educational moment for a person to create an innovative hybrid identity that might contradict traditional cultural practices.

Open to all families with children in grades preK-5, we featured picturebooks about Korea, Korean culture, or Korean American families and communities during each of the seven weekly sessions. The selected books were written in English, all authored or co-authored by persons of Korean heritage. We facilitated family-centered activities to engage the children with their siblings and parents. The books included: Bee-bim Bop! written by Linda Sue Park and illustrated by Ho Baek Lee (2008), Chef Roy Choi and the Street Food Remix written by Jacqueline Briggs Martin and June Jo Lee and illustrated by Man One (2017), Juna’s Jar written by Jane Bahk and illustrated by Felicia Hoshino (2018), New Clothes for New Year’s Day written and illustrated by Hyun-Joo Bae (9002), Sumi’s First Day of School Ever written by Soyoung Pak and illustrated by Joung Un Kim (2003), The Green Frogs: A Korean Folktale Retold retold by Yumi Heo (2004), and 엄마마중 Waiting for Mama written by Lee Tae-Jun and illustrated by Kim Dong-Seong (2007).

We designed each session to follow a common structure. Jongsun facilitated each session in Korean and English. Sessions began with an introductory activity to activate children’s cultural knowledge. Next was an interactive read-aloud (Fountas & Pinnell Literacy blog, n.d.) in which children and parents shared their thoughts and knowledge associated with the focal text. Sessions concluded with a literature response activity intended to surface children’s linguistic and cultural funds of knowledge about their Korean American identities (Moll et al, 1992). For example, during the session featuring the picturebook, New Clothes for New Year’s Day, the families discussed New Year celebrations in Korea. Corresponding with the New Year’s tradition of wearing the traditional Korean dress, Hanbok, and wishing a New Year’s blessing to family members, children and their parents created Origami Korean dresses. Children also learned and practiced bowing to elders on New Year’s Day.

Participants in the program included newcomers and first-generation Korean American children and their families. Among the families, varying factors included their arrival time in the U.S., their Korean and English language proficiency, and their immediate family member’s ethnicity. Every participant was Korean American. Some children had parents who were both Korean, while some were from interracial families: one parent was Korean, and the other was non-Korean.

The children’s ages ranged from grades preK-5. The number of participants varied across sessions. Table 1 shows the number of participants in the two sessions we highlight in this article: Bee-bim Bop! and Chef Roy Choi sessions.

| Session | Number of Children | Number of Parents |

|---|---|---|

| Bee-bim Bop! | 19 | 8 |

| Chef Roy Choi | 22 | 10 |

Table 1. Number of Participants

Focal Picturebooks

In this article, we share observations from two sessions when we explored Bee-bim Bop! (2008) and Chef Roy Choi and the Street Food Remix (2017). Bee-bim Bop! is a story written in verse by Korean American author Linda Sue Park, who won the 2002 Newbery Medal for A Single Shard (2001). Chef Roy Choi and the Street Food Remix (Chef Choi hereafter) is a 2018 Orbis Pictus Award honor book for outstanding nonfiction written by Jacqueline Briggs Martin and June Jo Lee, and illustrated by Man One.

Bee-bim Bop Activity

In the session featuring Bee-bim Bop!, after conducting an interactive read-aloud, Jongsun invited the children and their families to draw their own Bee-bim-bop on paper using colored pencils and markers. We observed parents’ thoughtful engagement in the activity as they sat with their children and discussed the ingredients children could include in their unique Bee-bim-bop creations (Wee, 2020). Correspondingly, children’s choice of ingredients for their Bee-bim-bop displayed their funds of knowledge as seen in fourth-grader Jessica’s drawing. (All children’s and family members’ names are pseudonyms). Moll and his colleague (1992) used the term funds of knowledge in their study to connect students’ funds of knowledge and classroom instruction. They explained that it has “its emphasis on strategic knowledge and related activities essential in households’ functioning, development, and well-being” (p.139) and suggested teachers need to incorporate students’ funds of knowledge in their teaching.

During the Bee-bim-bop activity, the families sat with their children. For young ones who needed more guidance, they helped them draw. Some parents talked about traditional ingredients for Bee-bim-bop with the children, including bracken ferns and bellflower roots, which are common in Korea, but challenging to find in U.S. markets. In doing so, they passed along their funds of knowledge about Bee-bim-bop to their children. The parents also watched children drawing their Bee-bim-bop, gave them positive feedback, and praised how well they did (Wee, 2020).

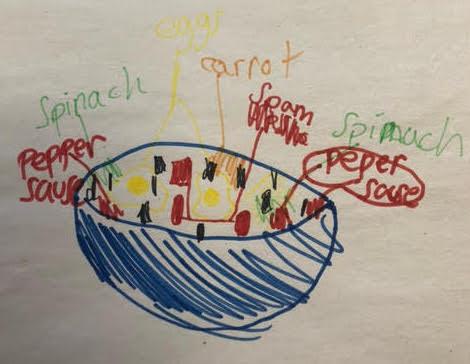

After creating their Bee-bim-bop on paper, children took turns describing to the group the ingredients they most enjoy in Bee-bim-bop. For example, Jared (preK) was a young boy who proudly shared his Bee-bim-bop drawing by saying, “Is my drawing the best?” Jared drew his Bee-bim-bop with different colors (See Figure 2), which suggests he knew that Bee-bim-bop is made with a variety of ingredients. Another young child, Charlie (preK), also used different color markers (See Figure 3) to indicate different ingredients. When Charlie was asked about his drawing, he said yellow was eggs, green was spinach, and orange was carrots, which are the traditional ingredients of Bee-bim-bop. In Charlie’s drawing, Jongsun wrote Korean words with Charlie’s answers during the activity. Young Jared’s and Charlie’s drawings reveal the children’s funds of knowledge about traditional Korean foods.

Across the group, out of nineteen children at the session, nine highlighted traditional Korean ingredients in their Bee-bim-bop, like Jared and Charlie. Eight children added ingredients that are not traditional of Korean Bee-bim-bop, such as blueberries, sweet potatoes, and pickles. The varying ingredients appearing in children’s drawings are suggestive of children’s transcultural experiences as members of a diasporic community in the U.S. southwest. This diversity of ingredients sparked comments and discussion among the families when the drawings were shared.

Sara (2nd grade) had a big smile on her face when she shared her Bee-bim-bop drawing, which had blueberries in it. She drew laughter from her mom and other parents. Instead of telling Sara that blueberries were not common ingredients for Bee-bim-bop, the parents complimented her by saying it was a cute idea to include blueberries. After listening to Sara, Sara’s mom shared her desire to cook more Korean cuisine at home.

Five children’s Bee-bim-bop drawings included Spam instead of ground beef (See Figure 4). We might infer that children’s families may substitute ground beef with Spam when they cook Bee-bim-bop. Even though Spam is not the traditional Bee-bim-bop ingredient, no one at the family storytime pointed out Spam as inappropriate. Bee-bim-bop with Spam may be viewed as a transcultural product since Spam was created in the U.S. as budget-friendly meat (DeJesus, 2014).

Interestingly, even though children included Spam, they did not forget to add pepper paste (Gochujang in Korean), one of the key ingredients of Bee-bim-bop. Gochujang is traditionally home-made and can be purchased at a Korean food market in the U.S. At the family storytime, transcultural products like Spam Bee-bim-bop seemed to be understood by the participants who shared the same transcultural experience because no one questioned it.

Food Truck Activity

Before conducting an interactive read-aloud in the session featuring Chef Roy Choi and the Street Food Remix (2017), the families viewed two short videos about Chef Choi’s Korean background and his fusion of Korean and American cuisines in cooking ramen. Alongside the videos, the picturebook highlights Roy Choi’s original food truck, in which he served fusion tacos with Korean barbeque. After the interactive read-aloud, the children created images of the kinds of food trucks they would like to visit, complete with menus.

Out of 22 children who shared their food trucks, twelve created food trucks with food that could be considered Korean food. Ten were food trucks with non-traditional Korean food: five dessert trucks, one fruit truck, one pancake truck, one chicken truck, and two trucks with no description. Interestingly, twelve children chose Korean food for their food trucks when the food choice was wide open.

Although the children did not feature fusion cuisine like Chef Choi, their food trucks showed an interesting mix of different foods. For example, one child drew a food truck with different kinds of Korean food and ice cream. This child labeled the names of each food drawn in Korean, such as 떡, 모찌, 전, and 아이스크.

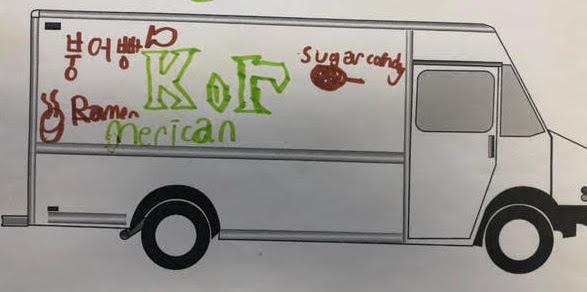

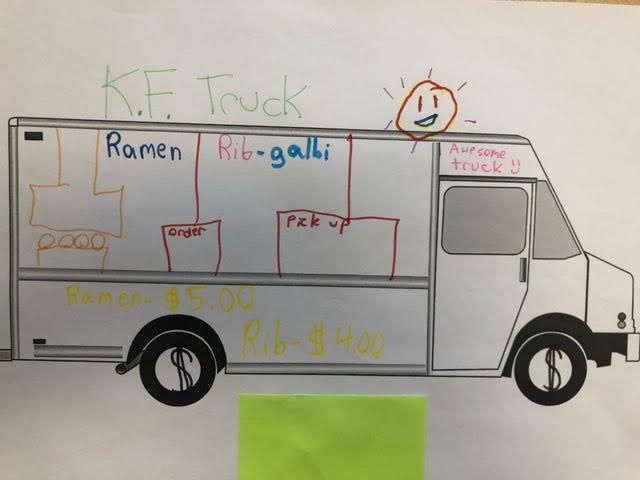

Ben (4th grade) named the food truck ”Kor Merican” and included food such as Bungeoppang (a fish-shaped bun with red bean paste filling), Raman, and sugar candy. In this drawing, a ladle is drawn for sugar candy. In Korea, a candy made in a ladle is called Dalgona. Inferring from the drawing, it seems that Ben knew about Dalgona and drew it on his food truck (See Figure 5). John (5th grade) created a truck named ”K. F. truck,” which served Ramen and Galbi, Korean barbeque ribs (See Figure 6). It was an interesting combination because Ramen is considered a cheap instant food, whereas Galbi is gourmet food that takes hours to prepare. Galbi is also often cooked for holidays, but serving Ramen on holiday would be unthinkable.

For this reason, Ramen and Galbi can be seen as an unconventional combination. However, to John, people’s typical perceptions of Korean food were not a barrier to creating such a combination. This unconventional combination shows children’s playfulness with the Korean food they know (Zhang & Guo, 2015).

The playfulness that children exhibited in their drawings made the parents laugh. Observing the parents’ comments like “Kids created fun Korean food trucks” and their facial expressions, it appeared that they were pleasantly surprised. Perhaps, they recognized children’s knowledge of Korean foods and children’s capacities to interpret the meaning of the food names in association with the Korean language.

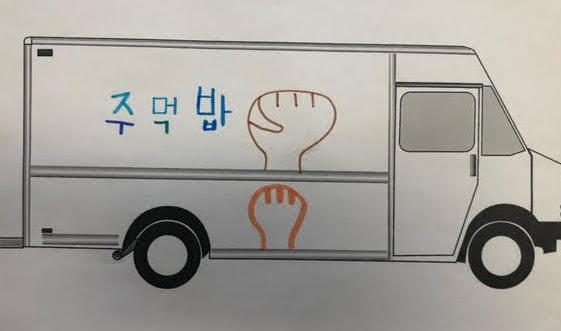

The parents recognized the wordplay that children displayed on the food trucks. For example, the parents were impressed when John, who created the “K. F. truck,” said K. F. stood for Korean Food (See Figure 6). The parents praised children for their witty decorations when they saw Hanah’s (3rd grade) drawings of a fist for Jumukbab (See Figure 7) and Ben’s drawing of a fish for Bungeoppang (See Figure 5). Jumukbab could be translated into ”fist rice balls”” in English, and Bungeo in Bungeoppang refers to one type of fish in Korean.

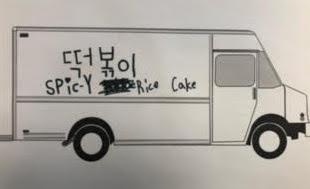

Collectively, children’s food trucks were artifacts of their knowledge of Korean food and written Korean words. For example, Ben wrote 붕어빵 next to his drawing of fish (See Figure 5), Grace (4th grade) wrote “spicy rice cake” underneath the Korean word 떡볶이 (See Figure 8), and Hannah wrote 주먹밥 on her rice ball truck. It shows that children understand what Korean words mean and how these foods got their names.

Perhaps these children chose to write Korean words because they knew many participants in the family storytime would understand them. If the same activity had been done in an English-dominant classroom, they might not have chosen to write the words in Korean or draw Korean food trucks.

Discussion and Implications

The storytime program created a transcultural third space (Bhabha, 2004) for children and their families to exhibit their hybrid identities and experiences via food-related bookplay activities. As shown in the Bee-bim-bop activity, family participants eagerly welcomed children’s merging of traditional Korean ingredients. As shown in the food truck activity, children made their Korean transcultural identities visible as both Korean and American (Hébert et al., 2008). Additionally, during the storytime program children utilized their oral and written Korean language skills as funds of knowledge in developing and discussing the artifacts they created.

Children’s active participation in family storytime and their written comments such as “Thank you for reading us books. They were great. The activities were very fun, too!” and “I like storytime because it was fun to listen to you reading books” showed us that children liked to listen to the stories about their heritage culture and participate in after-reading activities like those introduced in this article.

Although the outcomes of our project are exclusive to the families who participated in the program, we see some implications for supporting children’s literacy development in school settings and communities by mobilizing their funds of knowledge. This project highlights the significance of recognizing children’s identities and transcultural experiences through bookplay activities related to everyday experiences around food and mealtime (Zhang & Guo, 2015).

Concluding Thoughts

After the final session, families expressed their sadness about the conclusion of the program and eagerness to start a new family series with more books. We hope this project encourages others to engage with local community groups to develop family storytime programs that support and honor young children’s transcultural knowledge and experiences and biliteracy development.

References

Bhabha, H. K. (2004). The location of culture (2nd ed.). Routledge

Dávila, D. & Abril-Gonzalez, P. (2022). A family affair: Supporting the communicative capital and writerly identities of young children. Pensamiento Educativo: Revista de Investigación Educacional Latinoamericana, 59(2), 1-17.

Dávila, D., Abril-Gonzalez, P., Nuñez, P., & Pineda, M. (2022). “Mix learning with everyday moments”: A virtual recipe for early literacy development at home. Language Arts, 100(1), 21-34.

Dávila, D., Noguerón, S., & Vasquez-Dominguez, M. (2017). The Latinx family: Learning y la literatura at the library. The Bilingual Review/Revista Bilingüe. 33(5). 33-49.

DeJesus, E. (2014, July 9). A brief history of Spam, an American meat icon. Retrieved on April 22, 2024 from https://www.eater.com/2014/7/9/6191681/a-brief-history-of-spam-an-american-meat-icon

Fountas & Pinnell Literacy blog. What is interactive read-aloud? Retrieved on March 25, 2024 from http://fpblog.fountasandpinnell.com/what-is-interactive-read-aloud

Hébert,Y., Wilkinson, L., & Ali, M. (2008). Second generation youth in Canada, their mobilities and identifications: Relevance to citizenship education. Brock Journal of Education, 17(1), 50-70.

Hirst, K., Hannon, P. & Nutbrown, C. (2010). Effects of preschool bilingual family literacy programme. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 10(2), 183-208.

Li, A. (2919, May 28). Asian American chefs are embracing Spam. But how did the canned meat make its way into their cultures? TIME. Retrieved on April 22, 2024 from https://time.com/5593886/asian-american-spam-cuisine/

Louie, B., & Davis-Welton, K. (2016). Family literacy project: Bilingual picture books by English learners. The Reading Teacher, 69(6), 597-606.

Moll, L. C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & González, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory into Practice, 31(2), 132-141.

Timmons, V. (2008). Challenges in researching family literacy programs. Canadian Psychology, 49(2), 96–102.

Wee, J. (2020). The roles of parents in community Korean-English bilingual family literacy. The Reading Teacher, 74(3), 330-334.

Zhang, J., Pelletier, J. & Doyle, A. (2010). Promising effects of an intervention: Young children’s literacy gains and changes in their home literacy activities from a bilingual family literacy program in Canada. Frontiers of Education in China, 5.3, 409-429.

Zhang, Y., & Guo, Y. (2015). Becoming transnational: Exploring multiple identities of students in a Mandarin-English bilingual programme in Canada. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 13(2), 210-229.

Children’s Books Cited

Bae, H-J. (2007). New clothes for New Year’s day. Kane Miller.

Bahk, J. (2018). Juna’s jar (F. Hoshino, Illus.). Lee & Low.

Heo, Y. (2004). The green frogs: A Korean folktale. Clarion.

Lee, T-J. (2007). 엄마마중 Waiting for mama (D.S. Kim Illus.). North-South.

Martin, J. B., & Lee, J. (2017). Chef Roy Choi and the street food remix (M. One Illus.). Readers to Eaters.

Pak, S. (2003). Sumi’s first day of school ever (J. U. Kim, Illus.). Viking.

Park. L. S. (2001). A single shard. Clarion.

Park, L. S. & Lee, H. B. (2008). Bee-bim Bop! (H. B. Lee, Illus.). Clarion.

Jongsun Wee teaches at Pacific University, Oregon. She serves on the NCTE Children’s Poetry Awards Committee for the 2025 booklist and Children’s Literature Assembly Breakfast Committee.

Denise Dávila is a children’s literature and early literacy scholar at the University of Texas at Austin. She works with young children and families in community settings.

Authors retain copyright over the vignettes published in this journal and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under the following Creative Commons License:

WOW Stories, Volume XI, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on work by Jongsun Wee and Denise Dávila at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/xi-1/5.

WOW stories: connections from the classroom

ISSN 2577-0551