Inquiry About Censorship and Intellectual Freedom in Professional Development and the Classroom

Junko Sakoi and Yoo Kyung Sung

Children’s right to read, a fundamental human right, has faced increasing challenges due to a notable surge in censorship in recent years. A growing body of children’s and young adult literature has faced challenges and discouragement within educational settings (Friedman, 2022). In 2022, the American Library Association reported a record-breaking number of censorship attempts, the highest in its more than thirty-year history of data collection. The media daily report on censorship and its impact on schools across the country. In Arizona, HB 2495 was enacted into law and took effect on September 24, 2022, prohibiting the use of or reference to sexually explicit material without parental consent. This legislation has had a significant impact on educators in the Arizona school district where Junko Sakoi, a district professional development coordinator, is employed. Teachers have become cautious and reluctant to incorporate literature that includes sexually explicit content or that addresses historical and contemporary sociopolitical and cultural issues and events that are part of their curriculum.

In the summer of 2022, Junko participated in a workshop about banned books, which was hosted by a local university. Her motivation was to address the negative perceptions surrounding books that were once beloved by educators, families, children, and teenagers. During the workshop, participants, including classroom teachers and librarians, were given the opportunity to study the historical context of banned books, explore books that are being challenged today, and engage in discussions about the reasons behind these challenges and about the individuals or groups initiating them.

One notable aspect of the workshop was a session with Aida Salazar, where she discussed the current challenges faced by her book, The Moon Within (2019), in which a girl questions her changing body and her feelings toward a boy. Through this experience, Junko came to realize that censorship not only infringes on the First Amendment rights of young readers but also impacts authors who seek to share their life experiences and ideas with children and teenagers.

Inspired by the workshop, Junko planned the 2023 Professional Development (PD) to invite district educators to engage in dialogue about censorship issues and intellectual freedom. She also gathered practical classroom resources for teachers to incorporate into their censorship projects. Junko extended an invitation to Yoo Kyung Sung, a teacher educator specializing in literacy and literature courses at a local university, to collaborate as a partner in the PD. Together, they developed teaching concepts and expanded our resources for a classroom project focusing on censorship and methods for encouraging students to engage in critical thinking when reading challenged books. The goal was to create a supportive environment in which teachers and students could engage in critical and meaningful discussions about censorship and its broader implications.

Professional Development and Classroom Project

Identifying Challenged Books

We began by identifying titles that had been subject to censorship attempts nationwide. Our research involved consulting PEN America’s Index of Banned Books from 2021 to 2023 and the American Library Association’s (ALA) Top 10 Most Challenged Books Lists from 2001 to 2022. We then cross-referenced these lists with the district’s library catalog, revealing a total of 108 challenged titles available in the district as either district-approved texts or supplemental materials. These 108 titles are not challenged in Arizona but are in other states. To better understand the reasons behind those book challenges, we explored local and national news media, public library archives across the country, and the resources provided by PEN America and ALA. Notably, a significant portion of the challenged books did not have specific reasons listed for their classification as challenged literature. This lack of clarity underscores the complex and sometimes arbitrary nature of book censorship.

We also discovered a collection of books that faced censorship in the school district during the 1980s and 1990s (see Figure 1). According to the district’s library cataloger, the reasons for these book challenges included offensive language, violence, and sexually explicit content.

We compiled a comprehensive book list containing 108 titles, organized into four primary categories: picturebooks, chapter books, graphic novels, and verse novels. Within each category, we further classified the books into two subcategories according to the district policy: district-approved texts (used 70 to 75 percent of the time in the classroom) and supplemental materials (used 25 to 30 percent of the time in the classroom). This approach provided teachers with a clear understanding of how often these materials could be used in their instruction. For each book in the list, we included essential details, such as the author’s name, grade-level suitability, Lexile level, genre, themes, and a concise synopsis. Although we aimed to document the reasons for book challenges, this information was unavailable for most titles. Despite this gap, the comprehensive book list served as a valuable resource for teachers when planning their lessons, offering them a curated list of books suitable for various grade and reading levels and themes. The list’s structure and additional details enabled educators to select appropriate materials while being aware of their classification within the district guidelines.

The Inquiry Cycle as a Curriculum Framework

The Inquiry Cycle, as outlined by Short (2009) and Short and Harste (2002) in Figure 2, served as the framework for both the Professional Development and the classroom censorship project. This inquiry approach is characterized by its experiential, dialogic, and collaborative nature, focusing on processes that foster connections and reflections, encourage conceptual thinking, and transcend current understandings. The cycle aims to explore issues of significance to students, and students are encouraged to take personal, social, and civic action to effect change, as well as to formulate new questions for further investigation. Through this process, we designed learning experiences to explore, discuss, and inquire about important themes related to censorship and intellectual freedom. The inquiry-based approach created a dynamic learning environment in which both educators and students were actively engaged in meaningful dialogue and collaborative exploration.

Professional Development Session I

The inaugural district-wide Professional Development session, titled “Critical Inquiry About Intellectual Freedom and Censorship,” was conducted via Zoom. This PD session garnered considerable interest, with thirty educators spanning Grades K–12, including classroom teachers and librarians, in attendance. The session began with readings from two picture books: I Have the Right to Be a Child (Serres, Fronty, & Mixter, 2012) and We Are All Born Free: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Pictures (Amnesty International, 2016). These books were chosen to start conversations on children’s rights and serve as a springboard for deeper discussions on intellectual freedom, censorship, and human rights. The readings and discussions helped set the tone for the session, encouraging attendees to reflect on their roles in upholding intellectual freedom and fostering inclusive learning environments.

During the PD session, we delved into the history and current status of censorship movements, identifying and exploring who initiates challenges, the reasons for challenging books, and where these challenges occur. One of our guest speakers, a teacher, shared her personal experience of book removal during the attempted ban of the district’s Mexican American Studies program in 2010. Although the time constraints limited a comprehensive discussion of the incident, her story had a significant impact in illustrating the real-world effects of censorship on educators, students, and local communities.

Following her account, a vibrant discussion unfolded in the Zoom chat. Teachers and librarians candidly shared their concerns about censorship and reflected on how the attempted ban of the Mexican American Studies program had affected students and educators. They discussed the broader implications for the community, highlighting the potential loss of diverse cultural perspectives in education. One of the high school teachers expressed her mixed feelings in the Zoom chat, noting that it made her sad to have to seek caregivers’ permission for books that she knew her students would love to read. This comment resonated with many participants, reflecting the tension educators face when navigating censorship and its impact on teaching practices.

After the PD session, we analyzed the Zoom chat and collected written feedback from participants, gaining valuable insights into the needs and desires of teachers and librarians. The analysis highlighted a strong interest in further discussions about censorship, along with the need for more resources and strategies to address these challenges in the classroom setting. In response to these requests, we decided to organize another Professional Development session about censorship. This follow-up session aimed to continue the dialogue, address participants’ concerns, and share additional educational resources to help educators navigate the complexities of book challenges and promote intellectual freedom in their classrooms. The intention was to create a supportive environment where educators could collaborate, learn from each other, and find effective ways to advocate for the right to read and teach diverse literature.

Professional Development Session II

The second district-wide Professional Development session on censorship was held in person, with K–12 educators invited to attend. A student from Yoo Kyung’s censorship and children’s literature class, taught at her university, was invited as a guest speaker. The student presented her study on the censorship movement in Florida via Zoom. Her views on the current censorship movement nationwide empowered the educators. We realized that young people’s voices, perspectives, and experiences are always missing in our discussions around censorship. We must invite them because these issues directly affect them, their rights, their lives, and their futures.

The original agenda included discussions on book bans and censorship movements in the U.S. and global contexts. However, the session took an unexpected turn when we spent most of the time addressing concerns and confusion surrounding the ambiguous language in HB 2495, which had recently come into effect in Arizona. We also discussed books containing racial terms and racial slurs that have become targets for censorship. Some teachers pointed out how book censorship has impacted young people’s understanding of race, racism, peer relationships, and teaching. One visual arts teacher shared her hesitation to even mention the color black in the classroom, noting that some students associate it with racial slurs and respond with laughter.

Censorship Project in the Classroom

Several middle school teachers who participated in the Professional Development sessions launched an inquiry project focused on censorship in the classroom. Yoo Kyung and Junko held Zoom meetings with these teachers to share resources.

Some teachers began their lessons by reading I Have the Right to Be a Child (Serres, Fronty, & Mixter, 2012) to encourage discussions about children’s rights. This inspired students to ask why children have these rights and why they are significant. These discussions grew to include the rights children have within and beyond their school community, explored from different viewpoints, including those of young children, teenagers, parents/caregivers, and teachers. To broaden the students’ global perspectives, students were encouraged to explore a text set about children’s rights in various global locations. This text set featured books such as Hear My Voice/Escucha mi voz (Binford, 2021), a first-person narrative describing the struggles faced by children in detention at the Mexico–United States border, and Ten Cents a Pound (Tran-Davies & Bisaillon, 2018), which tells the story of a young girl in an unnamed Asian country who dreams of going to school.

Students then explored a text set of challenged books, identifying connections among the texts and selecting several titles to study closely to understand why they had been challenged. They also shared their thoughts on censorship by responding to questions posed by teachers, such as, Should anything be censored, and who gets to decide? One student highlighted the importance of teachers and caregivers/parents choosing reading materials for children based on age appropriateness, but disagreed with censoring books that discuss LGBTQIA+ identities and war because these reflect our lives.

Additionally, students shared their thoughts, questions, and reflections through free writings. One eighth-grade student closely read And Tango Makes Three (Richardson, Parnell, & Cole, 2005) and expressed his thoughts in writing. The book, an award-winning true story about two male penguins who adopted an orphaned penguin at the New York Central Park Zoo, has been ranked sixth on the list of “Top 100 Most Frequently Challenged Books: 2010-2019” reported by the American Library Association. It faces challenges due to reasons such as being unsuited for age group, presenting a religious viewpoint, and portraying homosexuality.

In his free writing, the eighth grader referred to the two penguins as gay and addressed the inappropriateness for young children to read the book. At the same time, the student also mentioned that this book would be a great resource for children to learn about gender diversity. This specific feedback from the student made us consider the importance of selecting precise language when describing a book. The use of the LGBTQIA+ label appeared to cause confusion for him, as he found the term “gay” to be somewhat casual and imprecise. This confusion might be linked to a broader issue arising from widespread censorship practices, where book labels can unintentionally misrepresent the complexity and accuracy of the content. For instance, in a book about two male penguins raising a penguin egg to form a family, the term “gay” might not be the most appropriate or accurate descriptor.

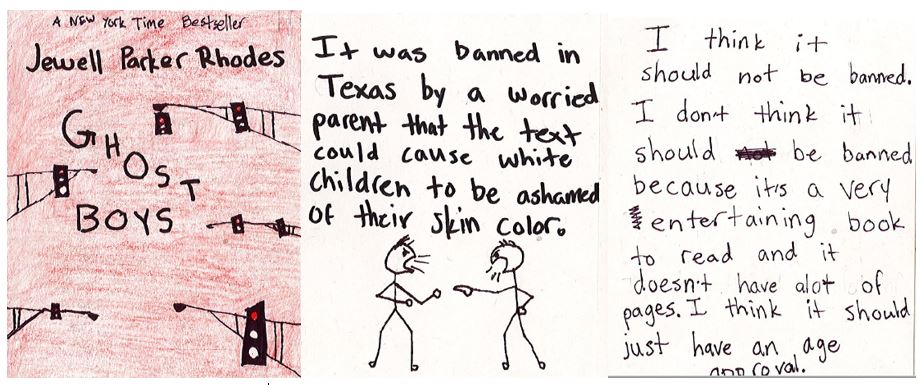

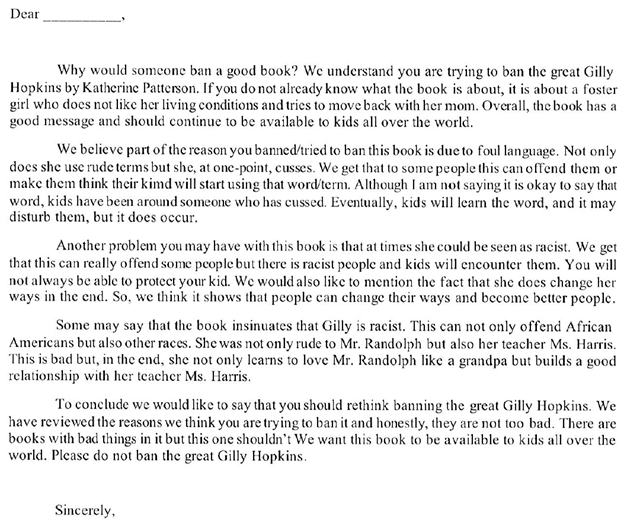

Beyond book censorship, students explored censorship across various media, including social media, the arts, music, comics, and movies. Working in small groups, they conducted research on different aspects of censorship. For example, they investigated the movie rating system by posing questions such as what a movie rating system entails, who established its guidelines, and the reasons behind its creation. They also examined music censorship, exploring its historical context, the people or groups responsible for implementing it, and its impact on musicians. As part of the inquiry project, challenged books were displayed in one of the middle-school grade classrooms, providing a tangible invitation to explore the theme of censorship (see Figure 3).Students presented their research findings through diverse formats, including comic books, reports, and posters. Figure 4 showcases a research report created by paired students who read Ghost Boys (Rhodes, 2018), which appeared on the American Library Association’s 2019 list of notable children’s books. It is a fictional story about a ghost’s journey exploring racism alongside other ghosts of Black boys killed by race-based violence. This book has faced censorship attempts in school districts in Florida and California due to what censors considered an inaccurate and stereographical portrayal of police officers in the United States (Kirkus Reviews, 2021). Additionally, several other students wrote letters opposing book banning, intended to be sent to school administrators (see Figure 5).

A group of seventh graders read Attack of the Black Rectangles (King, 2022), a fictional story based on true events. The story depicts a group of sixth graders who confront a censorship attempt of blacking out certain words and phrases in The Devil’s Arithmetic, a novel by Jane Yolen about the Holocaust. Following the reading, the book’s author, A. S. King, was invited to the classroom via Zoom. She discussed her book, and students were given an opportunity to ask her questions, such as what inspired her to write Attack of the Black Rectangles. They learned that this was based on true events that happened to A. S. King’s son at school, who took action against censorship. Meeting the author was a wonderful, authentic experience for the students. In their reflective writings, one student expressed feeling empowered by A. S. King and mentioned that she would talk to her parents, who had been preventing her from playing soccer because of her gender, despite her desire to join a soccer team and play.

Concluding Thoughts

These are challenging times for many educators, children, and teens. In our school district, we have noticed an increase in self-censorship, particularly regarding topics related to the Civil Rights Movement and LGBTQIA+ themes. These subjects are increasingly viewed as controversial and are often avoided in classroom discussions. This environment of ambiguity and confusion generates fear and promotes self-censorship among educators and students. For the sake of critical literacy, it is crucial that educators and students engage in discussions about censorship and explore the complexities of these issues. The following questions can help us reflect on book censorship and inspire us to take action to drive positive change (Short, Lynch-Brown, & Tomlinson, 2017, p. 209):

- Do we allow outspoken special interest groups to influence the removal of valuable yet controversial books from library or classroom shelves, or do we stand firm in our convictions and book selections?

- Are we engaging in self-censorship by exclusively choosing books on safe topics, or do we make selections based on quality and age appropriateness?

- Are we actively listening to young readers’ responses to books, or are we limiting our interactions to comprehension questions only? If not, how can we do better?

- Do we permit children to reject books they dislike, or do we insist that they read our chosen selections?

- Are we involving children in critical analyses of books for authenticity and the presence of stereotyped representations?

References

Friedman, J. (2022). Banned in the USA: The growing movement to censor books in Schools. Pan America: Freedom to Write. https://pen.org/report/banned-usa-growing-movement-to-censor-books-in-schools/

Short, G. K., Lynch-Brown, C., & Tomlinson, C. (2018). Essentials of children’s literature. (9 ed.). Pearson.

Kirkus Reviews (2021). School halts use of “Ghost Boys” after complaint. https://www.kirkusreviews.com/news-and-features/articles/school-halts-use-of-ghost-boys-after-complaint/

American Library Association

https://www.ala.org/bbooks/frequentlychallengedbooks/decade2019

Children’s Literature

Amnesty International. (2016). We are all born free: The universal declaration of human rights in pictures. Lincoln Children’s Books.

Binford, W. (Ed.), & Bochenek, G. M. (2021). Hear my voice/Escucha mi voz: The testimonies of children detained at the Southern border of the United States. Workman.

Rhodes, P. J. (2019). Ghost boys. Little, Brown.

Serres, A., Fronty, A., & Mixter, H (Trans.) (2012). I have the right to be a child (A. Fronty, Illus.). Groundwood.

Tran-Davies, N. Nhung (2018). Ten cents a pound (J. Bisallion, Illus.). Second Story Press.

Junko Sakoi has worked as a district Professional Development and Multicultural Integration Coordinator in Tucson AZ.

Yoo Kyung Sung serves as a professor in the Department of Language, Literacy, and Sociocultural Studies at the University of New Mexico. She teaches courses in children’s literature at the graduate and undergraduate levels.

Authors retain copyright over the vignettes published in this journal and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under the following Creative Commons License:

WOW Stories, Volume XI, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on work by Junko Sakoi and Yoo Kyung Sung at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/xi-1/6.

WOW stories: connections from the classroom

ISSN 2577-0551