Teen Reading Ambassador Program: Captivating Teen Readers

By Cynthia Ryman and Rebecca Ballenger

In 2018, Worlds of Words, Center of Global Literacies and Literatures in the University of Arizona College of Education initiated the Teen Reading Ambassador Program (TRAP). The goal of this program is to provide an opportunity for high school teens who have a love of literature and reading to gain a university experience and share their experience with their peers by promoting reading in their school communities. As with all new initiatives, it began with a thought, grew into an idea, and led to months of planning. As TRAP completes its sixth year, the program creators reflect on the hurdles they overcame along the way, including the arrival of COVID-19 and the need to quickly adapt to an online format during the 2020-21 school year. Each challenge provided opportunities for imagination, adaptation, and growth. This article provides an overview on the beginnings of TRAP, its essential components, challenges faced, and some lessons learned.

The Origins of TRAP

Worlds of Words has for many years sponsored programs that bring children and books together to “open windows on the world.” School field trips and Saturday morning workshops provide an opportunity for introducing elementary-age students to global literature. While high school groups sometimes visit the center and have partnered on exhibits, no specific programs had been developed for teens–a significant missed opportunity.

Rebecca Ballenger, the Associate Director of Worlds of Words, had some familiarity with what was available in terms of programming for high school students from sitting on scholarship award committees, volunteering to support the college and career counselors at a local high school, and raising her own two teenagers. She knew of early entry, dual credit, and other ways high school students can experience academic college life. She also was aware of summer camps, institutes, seminars, and conferences offered by universities around the country. Most of these programs are geared toward the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) fields and provide brief encounters, lasting from a single day to a few weeks. She had seen internships on college campuses for high school students in science and business fields. However, Rebecca did not find many university programs that provide experiences with children’s and adolescent literature.

She formulated an idea for an outreach program that would invite rising first-years through seniors in high school to the university campus for an academic year of in-depth literature studies around books written specifically for young adults. This would not be a book club. Yes, it would incorporate reading and discussing literature, but the experience would include something more. Teens would learn how to talk about literature and take what they learn into their school and home contexts. This would make the link to “leadership” that is part of virtually every college application. The focus would be around opening teens to viewing literature on a different level and sharing their enthusiasm around literature with others. In this way they would become an “ambassador” engaged in diplomatic efforts to turn other teens who are not actively engaged in reading into readers—one book at a time. This programming would help teens get comfortable with the college setting, give them something to talk about in their college applications, and inspire new perspectives on children’s and adolescent literature and the education field. Worlds of Words would fulfill their mission statement and possibly recruit a few students to pursue degrees in education. At this point in the programmatic formulation of this initiative, the big question was how to attract participants. Programs for teens are notoriously difficult to run and to maintain as teens have busy schedules that become increasingly more complicated as they approach graduation.

Even so, the idea was big enough to present to Worlds of Words’ director, Kathy Short, which occurred during a road trip. With Kathy as captive audience, Rebecca outlined the initial program planning. As the field expert, Kathy recognized key ways to polish the plan by capitalizing off existing outreach that had proven successful, such as author/illustrator visits to the center. This programming is especially popular because everyone wants to meet a published book creator. What if Worlds of Words invited the authors of the books read by participating teens to the center? The teens could interact one-on-one with the authors and ask questions about the writing process and topics covered in the novels, as well as make a personal connection. This was the draw that the program needed. TRAP had a vision and a way to draw interest, excitement, and engagement.

With a green light from Kathy, a modest budget, and the spring semester looming, Rebecca moved quickly to launch a pilot program. Rebecca created a webpage that outlined the program and provided an online application, incorporating policies from the UArizona Office of Youth Safety. She promoted the program on social media, listervs, e-newsletters, and any other available platforms. She personally contacted local high school librarians and English department heads to ask them to encourage their teen readers to apply.

It’s one thing to administer programming, it’s another to inspire thoughtful discussions around literature to expand understanding. Rebecca asked Kathy for an experienced educator to act as a partner in the work. Kathy recommended a college of education doctoral student and an instructor of an upper-division children’s literature class who had experience as a high school librarian. Less than three weeks later, Rebecca stood shoulder-to-shoulder with Cynthia Ryman in front of a group of eight teens at the orientation of the pilot program and first cohort of Teen Reading Ambassadors. The pilot program would last just one semester, but it proved that teens could be captivated by literature and the excitement of sharing their passion for reading with others.

TRAP Programming

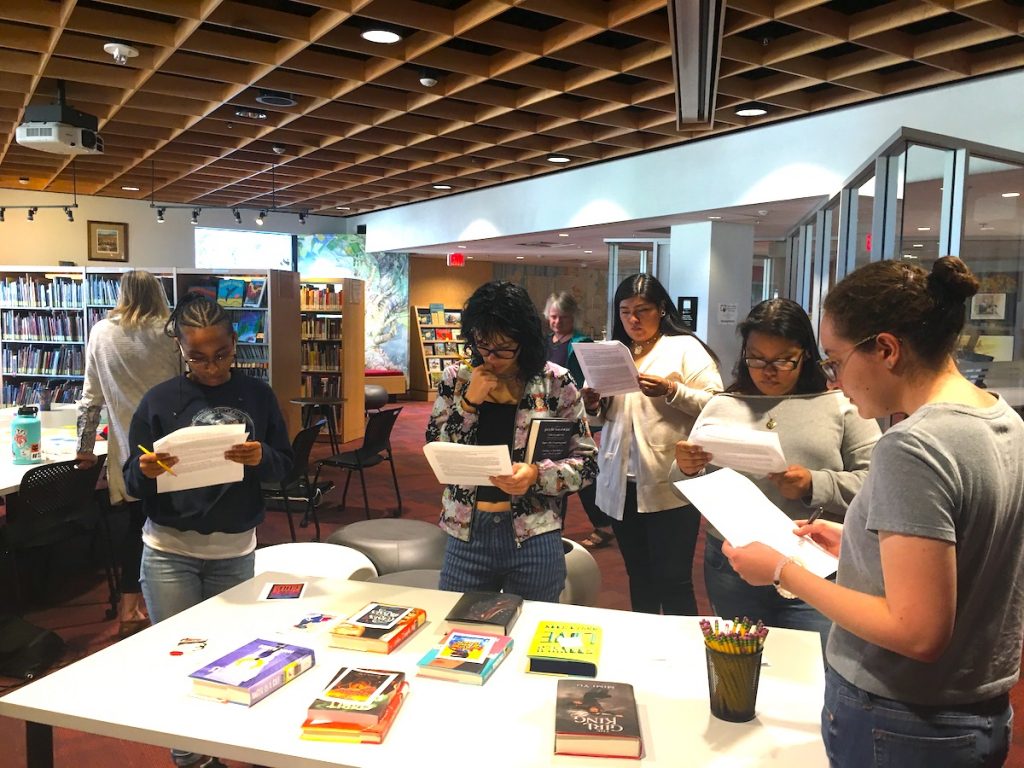

The Ambassadors meet once a month during the school year. The program offers teens an opportunity to explore books through in-depth dialogue around critical social topics and diverse ways of seeing the world. Each book cycle occurs over the course of two months. Ambassadors first discuss the book and create plans for how to share the book with peers. The following month they meet the author. Monthly meetings rotate between book discussions and ambassador training followed by author events.

The first meeting of each year is set aside for an introduction to the program and book selections. Teens who attend this orientation are given the opportunity to vote on the books that they will read during the year. Approximately fifteen to twenty books are set out during this first meeting as potential reading selections. These selections are based on several factors. One of the primary factors is the availability of the author to attend an author event and meet with the Ambassadors. When the program first started, these authors were mainly based in the Southwest within driving distance from the Worlds of Words Center. One of the unexpected outcomes of having virtual meetings during the 2020-21 school year was the ability to open the selection of books and authors to those living outside the Southwest.

A second important factor that goes into the book selection is the goal of providing a diversity of genres, social issues, and cultural perspectives. This includes being sure to include authors who represent diverse perspectives. Publication release dates are another factor that impact the book’s selection. Books that have been recently published or will be published during the school year are prioritized. After tallying the teens’ votes, the top four to five books are selected for the program’s reading list. The order that the books are read is based on the dates that authors are available for meeting with the teens during the year. Books are purchased through grants and donations for the program and distributed free to the teens. Each teen also receives a free book to share with their high school librarian or English teacher if there is no library.

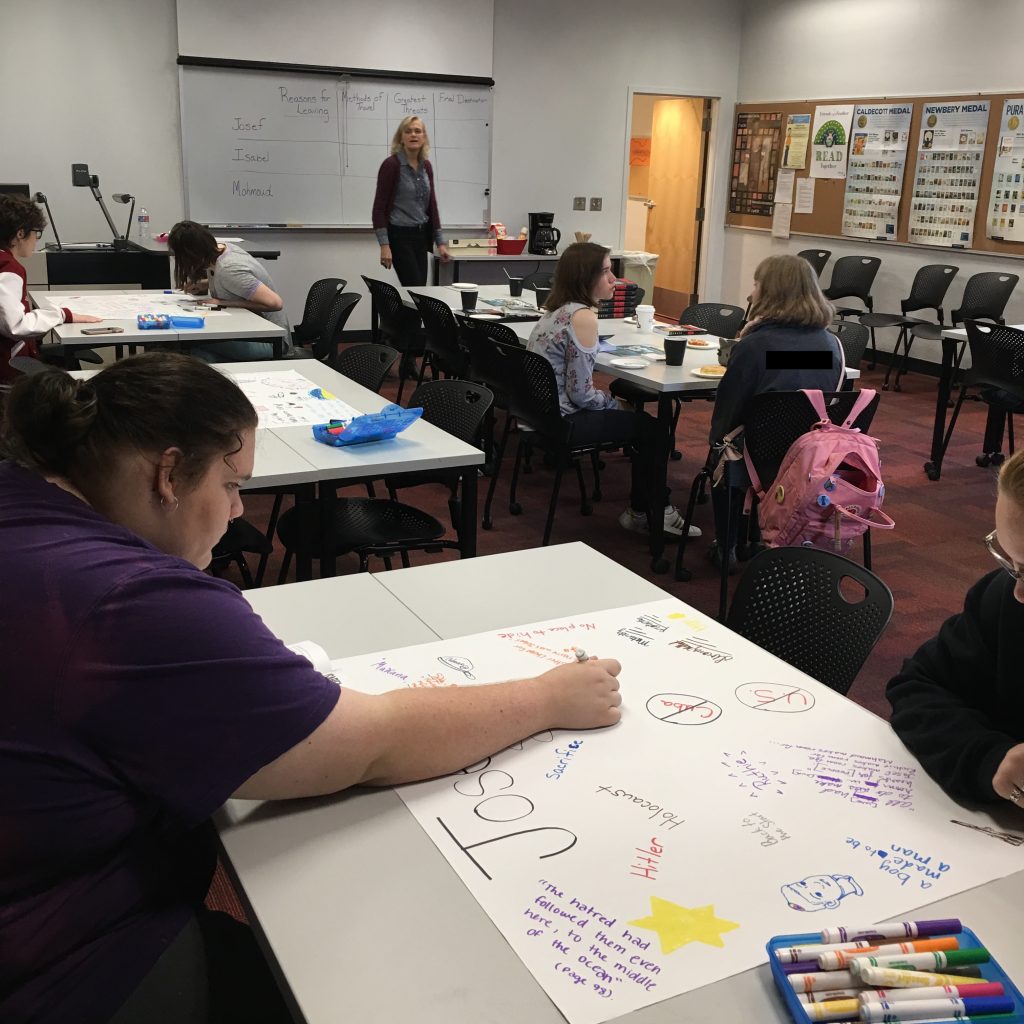

During the first half of a typical book discussion/reading ambassador training meeting, the teens come together to reflectively and critically dialogue around the selected novel. A dialogical approach allows for connecting the texts to the reader’s life and the realities of the various issues confronted in the texts. Table 1 lists several of the dialogue strategies that were used during the early book discussion meetings. Prior to introducing the dialogue strategies, Cynthia provides a brief introduction to a literary or critical issue addressed in the novel. These brief introductions provide the teens with a college-level experience on considering literature through multiple perspectives and various aspects of critical literacy. Critical literacy “melds social, political, and cultural debate and discussion with the analysis of how texts and discourses work, where, with what consequences, and in whose interest” (Luke, 2012, p. 5). The dialogue strategies that are used provide opportunities for the teens to unpack the problems, issues, and relevant cultural ideologies within the texts they have read. The novels selected for discussion provide ample opportunity for reflective dialogue on issues related to social justice, civil rights, the environment, and cultural locations.

| Date | Book Title | Author | Dialogue Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jan-March 2018 | Refugee | Alan Gratz | Graffiti Board: Teens sketched their connections to the events of the three refugees’ experiences. |

| March-May 2018 | The Porcupine of Truth | Bill Konigsburg | Consensus Board: Teens discussed the issues confronted in the novel and then selected one issue to research and explore. |

| May-July 2018 | Sad Perfect | Stephanie Elliot | Sketch to Stretch: Teens created a symbolic sketch capturing the meaning they made from the novel. |

| Sept-Oct 2018 | Walk on Earth a Stranger | Rae Carson | Reimagining Book Cover Design: Teens designed a cover for the book depicting the most impactful scene or personal connection to the novel. |

| Nov-Dec 2018 | Glitter | Aprilynne Pike | Heart Map: Teens drew an outline of the main character and considered the character’s values and loyalties as well as the outside influences on her worldview. |

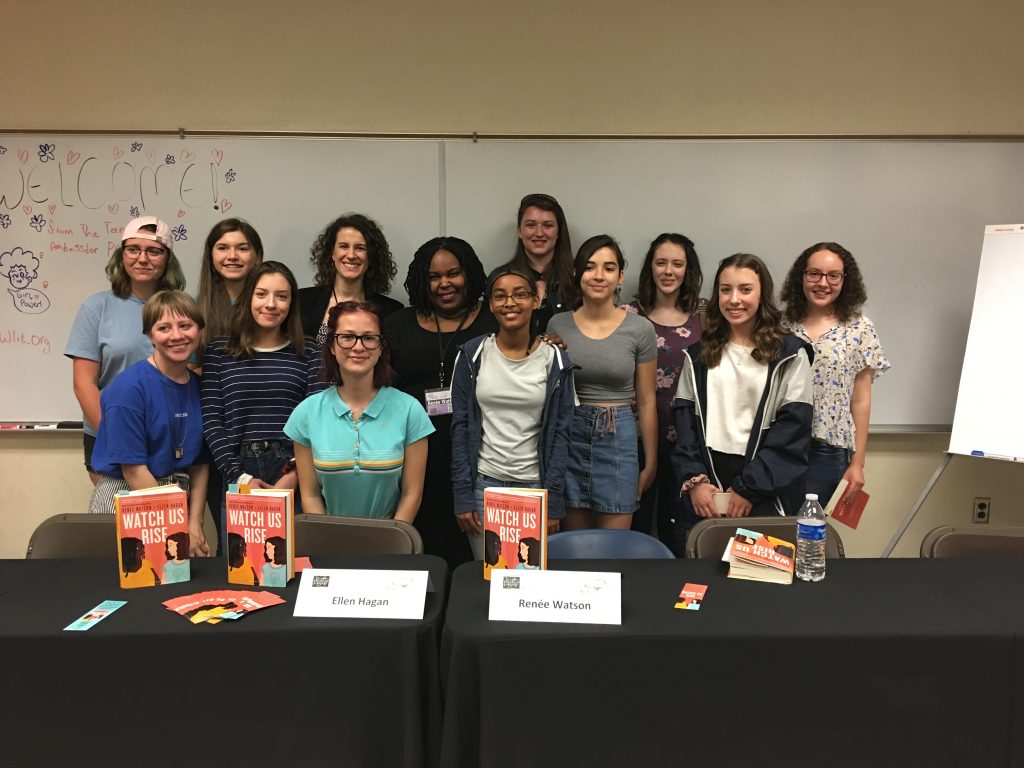

| Jan-March 2019 | Watch Us Rise | Renee Watson & Ellen Hagan | Found Poetry: Teens created a poem using the text from the novel to capture their connection to the novel and compiled them in a ‘zine. |

| April-May 2019 | Barely Missing Everything | Matt Mendez | Save the Last Word: Teens selected a section/quote from the book that impacted them most. These quotes were shared in small groups. Each group member shared their reaction to this quote/section and the selector of the quote gets the last word. |

| Aug-Oct 2019 | Echo North | Joanna Ruth Meyer | Hero’s Journey and Memes-units of information that are replicated culturally (Dawkins, 2016): Teens discussed the aspects of the journey made by the hero and the memes they connected with most. |

| Nov-Dec 2019 | Making Friends with the Dark | Kathleen Glasgow | Chart a Conversation: Teens used a chart divided into connections tensions to free write their responses to the book. They used their written responses to guide dialogue. |

| Jan-March 2020 | Dread Nation | Justina Ireland | Written Conversation: Several large charts were placed around the room labeled with various issues from the novel. Teens selected the issues that they wanted to address and wrote out their perspectives. Time was allotted for several rotations so that each person could read and respond to other perspectives. |

| April-May-2020 | Day Zero | Kelly Devos | Dystopian Connections: This was the first online meeting due to COVID. The online dialogue connected the novel to the issues and feelings of the teens toward the current dystopian reality. |

| Sept-Oct 2020 | The Voting Booth | Brandy Colbert | Post-Full Thinking: As teens read novel, they posted their reactions to events in a Padlet page. During the Zoom discussion, another Padlet page was opened for listing issues that continued to cause tension. |

| Nov-Dec 2020 | Anger is a Gift | Mark Oshiro | Webbing What’s On Your Mind: Formed breakout rooms during the Zoom meeting and groups discussed most salient issues. As a group they recorded the issues discussed to share in large group. |

| Jan-March 2021 | Ancestor Approved | Cynthia Leitich Smith | Read-A-Thon: Posted online prompts each hour during a 4-hour virtual read-a-thon to which ambassadors responded using photo imagery. |

| April-May 2021 | The Bridge | Bill Konigsburg | Sense of Self-Cultural Location: Teens selected 4-5 artifacts to share during the online meeting that symbolized their sense of self and cultural location. Discussion focused on the importance of listening to perspectives of others and what can be learned. |

Table 1: TRAP Book Selections and Dialogue Strategies Used from 2018 through 2021

During the second half of each meeting, the focus turns toward the ambassador aspect of the program. While teens have many opportunities through their school context to read and respond to literature, they may not have as much experience with navigating social and communication skills in the adult world. It is uncommon for teens to proactively seek adulting opportunities (Buckley et al., 2021). These types of opportunities create an opening for teens to develop a comfort level speaking to people, especially adult people, whom they do not know, a useful skill in college. As likely as it is that teens feel uncomfortable and awkward in high school, it’s even more likely they are not comfortable on college campuses. The ambassador portion of the meetings addresses these issues.

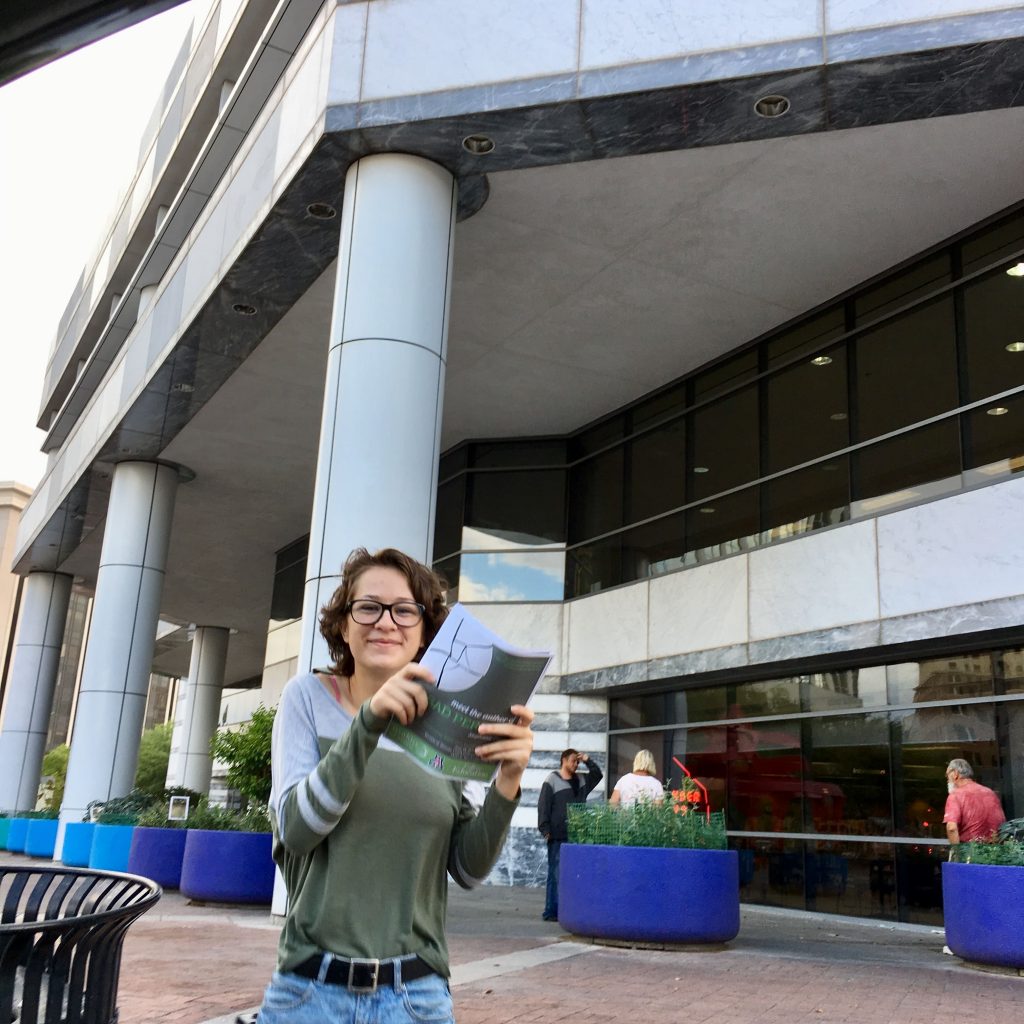

Rebecca developed multiple avenues for the teens to become involved in promoting literature and reading within their schools and community. In presenting these ideas she seeks the direction of the Reading Ambassadors as much as possible. For example, the pilot cohort decided that instead of having a private meeting with the authors, they wanted to open the author visits to their friends and community. This provided an opportune way for the teens to develop skills in promoting events and understanding the complexity of event planning. The teens learned how to design and distribute event flyers, promote events through social media platforms, create book displays for their libraries, and practice proper etiquette in marketing. The ambassador piece gives the teens invaluable skills related to not just promoting an event, but also coordinating and running an event. When an author visits the reading ambassadors in Worlds of Words, the teens plan how to set up the space, what types of refreshments to provide, and contact a bookseller to partner with. They welcome everyone to the event and introduce the author. They prepare questions and determine who will moderate the event. They also decide who will close the event. These types of skills may not be typically associated with a literature program, but they have become a cornerstone to what it means to be a Teen Reading Ambassador.

Self-determination (Deci & Ryan, 1985) plays a major part in programming for the teens. In addition to selecting their books and planning their author events, ambassadors also choose what online platforms they use for organizing. Over the years, they tried multiple platforms. For example, after using Google Docs while getting established, they decided it felt “too much like work.” They chose to try Padlet and, later, Discord. This control over their experience gives the teens a feeling of accomplishment and boosts their confidence, providing them with motivation to share with their peers and to continue in the program.

Reading ambassadors also experience the work that goes into partnering with other organizations. For example, they met up with students from the UArizona English Department’s Pine Reads Review to ask questions about how to do well in college. Afterwards, they recorded a podcast with the Pine Reads Review students around a YA novel that was not on their reading list. Additionally, each year the Ambassadors moderate a session in conjunction with the Tucson Festival of Books.

Because they are engaging in trial and error, Ambassadors are more likely to experience setbacks that they must adjust to (i.e., they are more familiar with rejection or failure and understand that everything will be fine). They are more adept at planning and organizing. They understand the different level of preparation required from asking a friend to participate versus a cold ask of the school librarian. They have to balance being star-struck by an author while also facilitating a public discussion. No longer confined to familiar contexts (school, sports, religious), Ambassadors are better equipped to interact with adults in professional environments.

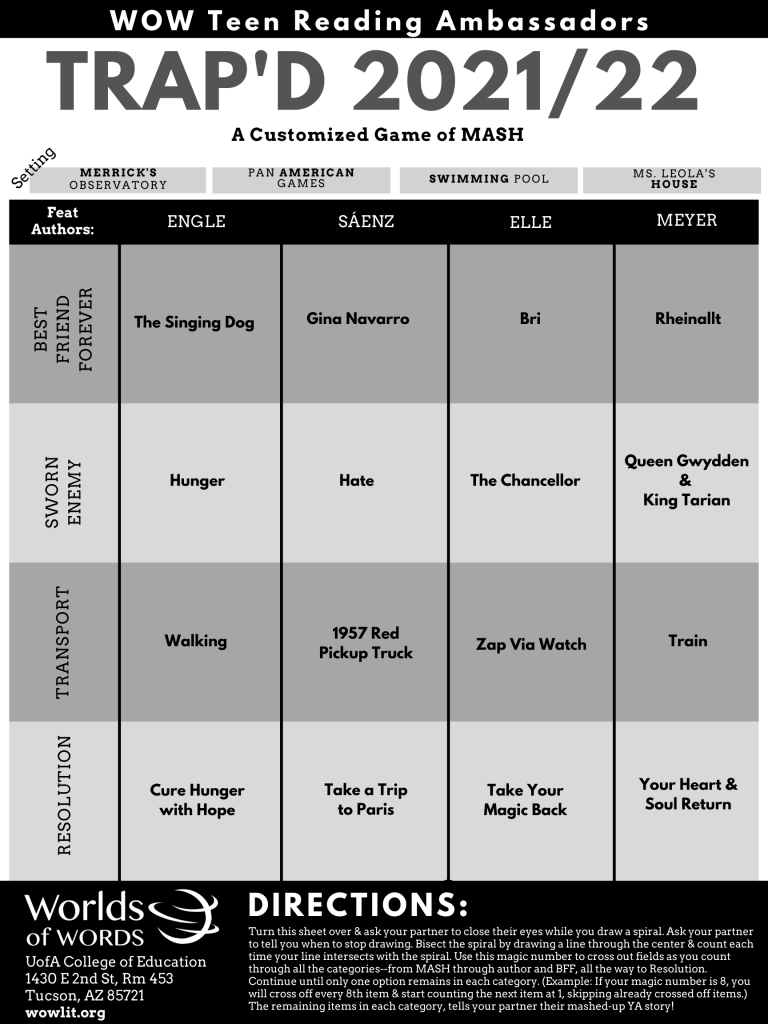

The final meeting of each year is a celebration, which is typically spent with an invited author. During this meeting, ambassadors receive a certificate of participation, play the fortune-telling game of MASH recapping the books they read, receive superlatives voted on by fellow ambassadors, and share their thoughts in an exit interview.

Challenges and Opportunities

TRAP aims to provide an opportunity for any high school teen to participate in a humanities-based university experience. In planning the program, Rebecca and Kathy did not want finances to be a barrier. There is no charge for joining the program and the cost of books provided to the teens and to their high school is covered by the program.

One of the challenges the program has faced is getting word out to the high school teens who may have never considered investigating programs like TRAP. This is where the need for creating strong school contacts becomes imperative. Over the course of the last six years, the program has gradually expanded and attracted teens from multiple area high schools.

Another challenge faced when the program began and met in Worlds of Words was transportation. At times, Reading Ambassadors have been unable to attend meetings because they don’t have a car or a ride and public transportation was inadequate. The program has hosted Reading Ambassadors from as far away as Baboquivari High School located in Sells, Arizona, approximately seventy miles from Tucson. Ideas to ease transportation constraints included paying for city bus fares or creating formal clubs within high schools with an on-site sponsor who could use school vans. Despite these efforts, transportation is likely to be an ongoing challenge.

During the closure of Worlds of Words due to COVID, the entire program moved to a virtual environment. This solved transportation issues while opening an unforeseen opportunity to expand the outreach of TRAP beyond local high schools. During the 2020-21 school year, reading ambassadors from Texas and as far away as London, England joined the program.

This discovery of the advantages of providing a virtual membership opened the door for new explorations and challenges. An international Reading Ambassador program has exciting potential in providing expanded outreach and broadened perspectives for considering global issues; however, expansion also brings challenges. Novels available in the United States are not necessarily available abroad. It also creates a challenge in shipping cost and timely deliveries. Time zones for teens living in other countries create a scheduling challenge. And, as every educator teaching during the pandemic has experienced, the teens had vastly different access to the internet and connective devices.

In creating TRAP, the hope was that reading ambassadors would open channels to discuss books with their friends and engage with educators in their schools. When teens took this one step further to make presentations in their classrooms, this felt like a win. One Reading Ambassador centered the program as part of her senior capstone, which they presented to a committee for a scholarship. In that presentation, they asserted that, “everyone has the right to read and … the ability to think critically about what they read.”

After four years working with teens, Rebecca adapted the program for middle school readers. This group has a more robust membership that requires additional support for the Reading Ambassadors as they gain independence and extensive communication with parents that is not common for teen programming. Another development has been the launch of the WOW Reads podcast (available on Apple, Spotify, and other podcasting platforms) with regular episodes around the books and author interviews and bonus episodes on a variety of topics related to children’s literature. Some reading ambassadors have been asked to serve as beta readers for authors interested in a teen reader’s perspective. Challenges and opportunities will continue to be explored as the program evolves and the group considers how the mission and vision of the Teen Reading Ambassador Program will grow.

Lessons Learned

Along with the challenges and opportunities, there have been many lessons learned. Maintaining, and more importantly growing, a program requires a reflective consideration of which aspects of the program work well and which aspects should be changed. The essential elements of the program focus on quality literature, the tools for ambassadorship, and interacting with published authors have worked well in attracting teens interested in literature and writing. Attracting teens to the program and maintaining involvement are two very different challenges.

During the first two years, the program struggled to create a cohesive sense of community within the program. This was an aspect that we knew needed to change. Exit interviews with Reading Ambassadors indicated that monthly meetings are not enough to maintain consistent enthusiasm or meet the desire for the teens to just talk to one another. Within each cadre there has been a select group of teens who felt comfortable engaging in discussion during meetings and helping to lead the author events. Other members were observers who did not develop a connection to a group identity. Ownership of the process is a cornerstone of the program and that requires Reading Ambassadors to build social ties within the group.

This cohesion was especially challenging the first year of the Middle School Reading Ambassador group when a partnership was attempted with a junior high in a different state. On the surface, all the elements appeared to be in place — funding, official agreements and administrative buy-in, a shared planning process, and technological tools. Additionally, both groups existed in communities that included strong local authors. However, the two schools had combined membership that spanned sixth to ninth grades, which created a challenge for book selection and engagement during the literature discussion. And although technology used included high-quality virtual meeting spaces, telepresence robots, and a collaborative web platform, the two groups had little successful interaction. Even with all the tools and good intentions, the collaboration didn’t work as hoped and was not pursued a second year.

While it is beyond the scope of this article to delve into social identity theory, it seems reasonable to assume that the teens who apply to TRAP hope to find a group that shares similar values and interests to their own. According to Stets and Burke (2000), group identity fulfills a need to not only feel valuable and worthy, but also competent and effective. For this to occur, the program has to provide a safe space for the teens to freely share their personal perspectives and feel supported by the group. This sense of connectivity and acceptance takes time to build and requires the development of strong social ties through relationships.

A couple of things became evident. Ambassadors responded better to text messages than email and they had robust private discussions outside of the program over Instagram messaging. The traditional form of communication used in programming just didn’t connect. But knowing these things and having the time to invest are two different things. Worlds of Words employed interns working on a number of projects in the center, including TRAP. But a partnership with the Leadership and Learning Innovation major in the UArizona College of Education, whose focus is on teaching in non-traditional settings, gave Rebecca an idea on a new type of internship—one that focused less on operations and more on relationships.

Rebecca invited undergraduate interns to join TRAP leadership team during the 2020-21 school year. These interns were tasked with creating a group text chat, following up with Ambassadors individually on their assignments, and creating dynamic e-blasts to replace traditional email messages. The teens formed an immediate and strong bond with these interns. Their closer proximity in age and relatability to the teens seemed to draw them into feeling freer to interact and share their perspectives with the interns and with each other. The interns maintained close contact with the Reading Ambassadors and encouraged their participation in online postings through Instagram, then Padlet, and finally with Discord. The interns’ role as mentors became invaluable in developing and maintaining social ties.

As the teens developed comfort with their social identity within the group, they also showed greater confidence to take on roles within the program. Each of the teens freely volunteered to post invitations to the author events on the TRAP Instagram account. Those with experience moderating and closing author events, willingly acted as peer mentors to who volunteered for the first time. The group members became highly supportive of each other and excitement in participation grew. Adding undergraduate interns to the team as mentors to the teens provided an important missing element, a generational bridge that encouraged the teens to invest in the program in a more dynamic and committed way.

Final Thoughts

The best way to summarize TRAP and the impact of this program for teens is through the words of the ambassadors themselves. In their exit surveys, we ask them to indicate what they like most about being in TRAP. Here are some the responses:

- I liked the people because normally it’s hard for me to feel comfortable around new people, but this group made me feel welcomed and comfortable instantly and I love talking to them.

- When we meet authors and ask important questions that help in our understanding of books and the writing process.

- The connection through the pandemic.

- It was something fun to experience and enjoy and I never had a safe place to talk and rant about books, so this was my favorite time in the year and the books chosen are amazing.

- I liked the opportunities to learn and explore various books through this program.

- I liked the excitement of discovering new things about books we’d read and the accomplishment of creating flyers I felt proud of. I enjoyed whenever I felt I had come up with a better way to ambassador.

- I just really like trying to get others to read, especially teens because so little do enjoy reading for fun.

- I really liked how in this program we went beyond just reading. We share our love of reading in our community and met the people who wrote each book. We got to know both the book and its creator.

- I liked the environment it was a healthy and balanced one I felt like I fit in and I had such a fun time it was one of the things I will cherish forever.

- I really enjoyed my time in this program. It taught me to look at things in multiple perspectives and share my joy of reading.

- Keep the program going I’m hoping it will be around long enough for my brother to join!

- I am grateful for the opportunity to get to know others who share my love of books and reading. I’m also thankful for the chance to improve my social and speaking skills.

Deploying a program similar to this one in a classroom or school library is possible. For example, middle and high school librarians who can have students enroll as library aides may decide that part of the student aide’s learning can be around learning how to host community events. However, it seems most likely that a similar program would take form as an afterschool club. Because of the current climate of book challenges, book selection for a school program like the Reading Ambassadors will most certainly come under a more critical eye. Additionally, funding would have to be secured as books alone cost about $2000 per year, and then snacks, printing, and other materials must be factored in. To find local authors, educators can consult with their nearest chapter of the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators. Virtual author visits broaden the range of authors available, but those visits don’t always have the same engagement level. To compensate, Worlds of Words requests signed bookplates from the authors we meet virtually so that those can be distributed in the room towards the end of the author event.

The experience of developing a program that supports and encourages the importance of literature in the life of teens and having the opportunity to learn from their perspectives has been extremely rewarding. We view this program as a Bildung (von Humbolt, 2012), a process of harmonization in which experiences in transacting with literature and group dialogue lead to broadened perspectives and these broadened perspectives lead to growth and transformation. The program provides an opportunity for teens to experience a diversity of perspectives through literature. They are challenged to reflect on literature in new ways and discover ways to share their insights and love of literature with others as ambassadors. We hope that the teens who participate in the program begin to recognize the power of literature to transform perspectives and view themselves as ethical agents for positive social transformation in their worlds.

Additional Resources

For more information on the Worlds of Words Teen Reading Ambassador Program, including a full reading list: https://wowlit.org/wow-teen-reading-ambassadors/

Permissions Paperwork for TRAP: https://wowlit.org/wow-teen-reading-ambassadors/#PAPERWORK

Teen Reading Ambassador’s Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/wowteenambassadors/

Worlds of Words’ Middle School Reading Ambassador Program: https://wowlit.org/wow-teen-reading-ambassadors/middle-school-reading-ambassadors/

Literature Read by the Teen Ambassadors Mentioned

Carson, R. (2015). Walk on earth a stranger. Greenwillow Books.

Colbert, B. (2020). The voting booth. Disney-Hyperion.

Devos, K. (2019). Day zero. Inkyard Press.

Elliot, S. (2018). Sad perfect. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Glasgow, K. (2019). Making friends with the dark. Delacorte.

Gratz, A. (2017) Refugee. Scholastic Press.

Ireland, J. (2019). Dread nation. Balzer & Bray.

Konigsberg, B. (2015). The porcupine of truth. Arthur A. Levine Books.

Konigsberg, B. (2020). The bridge. Scholastic Press.

Mendez, M. (2019). Barely missing everything. Atheneum/Caitlyn Dlouhy Books.

Myer, J. R. (2020). Echo north. Page Street Kids.

Oshiro, M. (2019). Anger is a gift. Tor Teen.

Pike, A. (2016). Glitter. Random House Books for Young Readers.

Smith, C. L. (2021). Ancestor approved. Heartdrum.

Watson, R. & Hagan, E. (2019). Watch us rise. Bloomsbury.

References

Buckley, K., Mokuau, D., & Mastrull, A. (2021, August 5). Prepping teens for adulthood [Conference presentation]. School Library Journal Teen Live!, Virtual Event.

Dawes, R (2016). The selfish gene. Oxford University Press.

Deci, E.L. & Ryan, R.M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum Press.

Luke, A. (2012) Critical literacy: Foundational notes, Theory into Practice, 51(1), 4-11.

Stets, J. E., & Burke, P. J. (2000). Identity theory and social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(3), 224-237.

von Humboldt, W. (2012). The theory of bildung. In I. Westburg, S. Hopmann, & K. Riquarts (Eds.). Teaching as a reflective practice: The German didaktik tradition. (p. 57-64). Routledge.

We wish to acknowledge and thank Libraries LTD for their support of our reading ambassador program by providing funding for the books given to the readers in our program.

Cynthia Ryman is a lecturer at California State University Monterey Bay, Marina, CA.

Rebecca Ballenger is the Associate Director of the Worlds of Words Center for Global Literatacies and Literature in Tucson, AZ.

Authors retain copyright over the vignettes published in this journal and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under the following Creative Commons License:

WOW Stories, Volume XI, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on work by Cynthia Ryman and Rebecca Ballenger at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/xi-1/7.

WOW stories: connections from the classroom

ISSN 2577-0551