“I Have the Right”: Connecting the Human Body to Human Rights

Holly Hardin

“I have the right to have a name, a nationality, an identity… I have the right to go to school… I have the right to be protected from racism. And I have the right to be loved.” Reza Dalvand’s (2023) book I Have the Right: An Affirmation of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child kicked off our unit on the human body for our science class. My seventh and eighth graders, despite wanting to be adults on so many levels, also love being read picturebooks from time to time and making big idea connections, so were captivated and willing to engage with me on how this might link to the human body. After reading the brightly colored, beautifully illustrated book, we used a consensus map to create a list of other rights we believe we all have or should have, before taking a look at the actual UN declaration. As we shared our maps, we discussed different commonalities and differences. I asked them who or why people might be denied these rights, or how migration might positively or negatively affect them.

The next day I began laying out the unit in a familiar project format. I shared with them that in exploring our body systems–digestive, reproductive, skeletal, muscular, endocrine, nervous, excretory, and circulatory–we must ask ourselves how these systems are impacted by our surroundings, and that our project would help us do this. Like many things in our classroom, much of the work along the way is ungraded, but the prep work and research is essential for the final outcome. Students received a checklist to see these steps laid out, even though we weren’t starting the actual project right away, as a way to see where we were heading.

Reframing Our Human Body Study Around Human Rights

I teach in a combined seventh and eighth grade class in a public Montessori magnet school in Durham, North Carolina. I cycle through two groups of 25 students each day that make up our 50-person community, as we call it. Each year we welcome about 25 new students into our community as seventh graders, as we continue to build with the rising eighth graders. Students are not separated by grade for instruction, and when it comes to science, we simply focus on the seventh-grade curriculum one year and eighth grade the next, as neither depends on the other.

Though I primarily teach science and math, our school is configured in a way that we are encouraged to collaborate across subject matter. This includes one day in our schedule where we open a moveable wall between our two classrooms and students engage in open work time, as well as cross curricular project work or field studies. Even when not directly collaborating, working so closely with just one other teacher means I am able to build off of lessons from humanities, allowing even more depth within our science and math work, which was the case for this project.

In summer 2023, I attended the NEH Summer Institute entitled “We The People: Migrant Waves in the Making of America” where we examined migration as a constant in US history, through a focus on the untold and silenced stories of people of color often left out of traditional narratives. At the end of the institute, we worked to create our own text sets, applying what we learned to our own classrooms. In deciding which science unit to use, I thought about the one that I was often least excited about teaching, in part because I had no project or grounding study within it that helped students create meaning. For me, this was our seventh-grade human body unit. A clunky unit, with very generic and broad standards, there was a lot of room to envision both a text set and accompanying project for students. Additionally, students would have just finished a unit on migration and would be concurrently studying dystopian literature in humanities, a topic that quite lends itself to a discussion of human rights and control of human bodies.

To create this text set, I asked myself a couple of questions linking our science unit to the topics of the summer: How is our body connected to the land? How does bodily autonomy change when we move, stay, or return to a place? How does our study of the human body systems link to migration and a study of human rights? I knew I wanted to focus on body systems under the framework of bodily autonomy and how the presence or absence of human rights impacts the body itself. In this political moment, with growing attacks on women, nonbinary, and trans people, this project seemed even more relevant, as the concept of bodily sovereignty to captures all the pieces of where we live that affect how we care for our bodies.

As I collected books, film, and other pertinent texts, I tried to organize the works under six categories: The Right to Eat Our Own Foods; The Right to Reproductive Freedom; The Right to Be Safe in Our Bodies; The Right to Love and Be Loved; The Right to Maintain Our Connections to the Land; and The Right to Play. I anchored each right with a poem, and made sure each included picturebooks, young adult novels, a visual component, and interactive websites. Though many of the texts could fall under a multitude of human rights, and for the project students did not necessarily know how I categorized them, this gave me a starting point for gathering the inspiration for our unit. In this article, I’ll share about the project that utilized and was built on this text set.

Inspiration from the Texts

After a few days of whole class overviews on the science behind each body system, making sure each student had a basic understanding of function and related organs, we took a day to explore the other picturebooks in our text set. Books were laid out at stations, where students were given time to explore the books and think on two main questions: What human rights do you think the books are discussing & why? And what body systems might be linked to or affected by the protection or denial of that human right?

Just as teachers loved the time to explore text sets in the NEH Summer Institute, students also eased into the idea of snuggling up on the flexible seating in the room with their group and trying to answer the questions. I spread books from my text set, along with a few additional titles I had identified, across tables around the room. A few tables offered both a picturebook and a YA novel, like We Are Water Protectors (Lindstrom & Goade, 2020) and Amazona (Canizales, 2022), whenever they had similar themes. They were welcome to explore either, but my hopes were in our limited amount of time to pique their interest in the YA novel to come back to, which students did throughout the year. One student made their way through multiple selections by Aida Salazar after reading Land of the Cranes (Salazar, 2022) liking her writing in verse. One student picked up Hear My Voice/Escucha mi voz (Binford, 2021) every day for two weeks during our solo time–a 15-minute time in the day where students engage in a solo activity silently–carefully studying each illustration, going back and forth between English and Spanish.

The only thing I would change about this particular part of the experience would potentially be to stretch it over a two-day period or utilize our flexible Wednesday schedule for a longer experience, as students were desirous of more time dedicated to just the texts. I think that would also have allowed me to share some of my non-written texts, such as the artwork, photography, and online material to explore, which I had left out of the stations. While I gave the class the link to my text set for later research, I think that is a very different experience than protected time to explore it, especially for students for whom research is newer. Students were much more likely to return to the picturebooks than any others. When most students had picked their ideas, and even were far along into their project, one student who seemed particularly stuck I encouraged to go back to those titles. After a class period of exploring, he brought up Salma the Syrian Chef and excitedly knew that his focus would be on the right to eat food (See Figure 1).

The next day we reflected on what we noticed about themes, body systems, and human rights. This reflection made discussing the culminating project easier, both because the books provided support potentially in picking a body system or human right for students needing more scaffolding, but also in providing inspiration in the illustrations and links to real life phenomena, some of which directly affected them. As often occurs, a student questioned the link to science. I let other students provide answers for this, but also shared that part of our responsibility is to learn how our body systems function so that we can better care for our physical needs and the needs of others.

One aspect of the project would be detailed science research about at least one system to learn more about its organs, their specific functions, and how they are impacted by outside conditions. But another piece involved how knowing scientific facts are used to shape our society. If we know what our bodies all need, we can also examine what human rights should be protected to better meet those needs. It’s a real-world application that we see play out in the world around us, from not having safe places to play, to being forced to live in a polluted area, or the very devastating impact of war. All of these conditions can greatly impact our physical and mental wellbeing, and we can use many things to justify the need to shift conditions, including science.

Project Plans

At this point the project became more self-paced, and students had to make their way through a deeper exploration of a few systems of their choice through readings, simulations, microscope work, and more. This work allowed students to better know the body so they could land on what they might choose to focus on for their project; take a checkpoint on their basic understanding of all the systems and general functions; begin the required research for their project; and submit a project proposal. The project plan that I gave to students provided structure for this work. Some of these pieces could be done as a group, to balance out the project which was going to be an independent endeavor. The classroom was full of activity over the next week as students worked through these tasks, at times revisiting the text set, both of their own accord, and sometimes in encouragement from me if they were stuck in the planning stage.

Throughout, another immediate world issue was at hand, directly connected to the uptick in force in the genocide in Palestine. During the last days where the body systems were being introduced, a student mid-endocrine system lesson turned and started shouting at a Muslim student in our classroom. We all froze. Before I could even process what was happening and start to escort the student out of the room, a few voices lifted, speaking over his continued retorts: “That is not right!”, “That’s racist!”, “Stop bullying him.” I came back into the room after getting the student to a safe place to process, to several students checking on their classmate, doing what they could to make sure he was OK. Proud of students’ responses, but still very shaken up as a class, it made the next day’s lesson on human rights seem even more pertinent.

When the young person who yelled anti-Muslim language returned to the classroom several days later, it was soon clear that something had shifted, and that he had partaken in more nuanced conversations about the attack on Gaza with his family. This happened as I worked with him 1:1 to give him an abbreviated version of what others had done, and when I asked him what human rights he could name, he immediately shared “The right to food, though the United States and Israel don’t think that’s a right.” For this student, being able to be in control of what he was learning and coming to his own conclusions was really important in how he processed things. The fact that he might undertake a project that had him reflect on his own behaviors, that wasn’t being forced by an adult, was critical. It also helped aid the healing process within our own classroom.

As students started to form their project plans, they met 1:1 with me, to assess what they might still need in terms of research (especially around the human right itself) and in project materials, but also added their human right to a group art piece in the shape which was displayed as part of our project showcase (see Figure 2). We had discussed the multi-faceted meanings of a heart, from our emotions, to love, to the central idea or driving force of a group, to its actual anatomical purpose, so this image seemed to be a good tie into our project. Again, it also served to be a repository of ideas that helped those who were stuck have a list of rights all in one place, and helped other students know someone else was working on a similar idea if they needed a thought partner during their work on their final project.

Figure 2. Classroom watercolor heart mosaic spotlighting all of the human rights we were researching.

In addition to the formal checklist of work that students completed during this unit, we did more informal reflections throughout to spur ideas, including linking it to their humanities work. This often happened at the start of class when we were still all together, before students set forth on their work plans for the day. In the first quarter students discussed migration, which can impact people’s bodies in all sorts of ways, both positive and negative: from having to move away from foods that were staple parts of your diet, to moving to find safety in expressing your gender identity. So one question discussed was: How are our body systems impacted by our movement and our surroundings? In the same quarter students were engaged in dystopian studies, which usually are situated around societies that make decisions affecting citizens’ rights, so we asked: How do we know if these decisions are good for us? What things in society might not let our body systems function as they should? For example, how do things like the right to play protect the health of our circulatory system; or the right to clean air affect our respiratory systems? Having these mini seminars both to kickoff class, as well as on our Wednesdays which are more open worktime days, served to get students thinking about the ways rights and our bodies are inextricably linked in a variety of ways.

The research for the project had 7 parts.

- Purpose/Function of your organ system

- Organs and parts of this system (this should include details about what they are/how they function)

- Using the UN Declaration on Human Rights on the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, what human right is linked to your organ system & how it is connected?

- Using your own research or one of the current event/case study articles provided by Ms. Hardin, find 2 current events that spotlight your right and organ system and has an impact on them.

- How might being denied that right affect your body system?

- Does it lead to disease or medical conditions? Name at least 2 diseases or medical conditions. Include symptoms and how the problems are treated (if treatable).

- Identify at least 2 ways we can protect this human right and thus protect or improve the quality of your organ system.

In this process, I failed to have what students needed initially for the fourth question well compiled, which was arguably the hardest part for students to find. In two years when I lead this project again, I will definitely work on locating more sources for students to access so their reliance on me becomes less. Otherwise, students were self-sufficient in completing this work.

Showcasing Their Learning

Once their research was complete, students had some flexibility in how they showcased this learning including, but not limited to a formal paper, poster, presentation/slides, brochure, model with labels, illustrated children’s book, dystopian short story, proposal for the city or county government of Durham, an analysis of the rules of the dystopian society in their humanities novel to address how they each limit or increase the functions of the human body, or a detailed book synopsis (using one of the books from our text set).

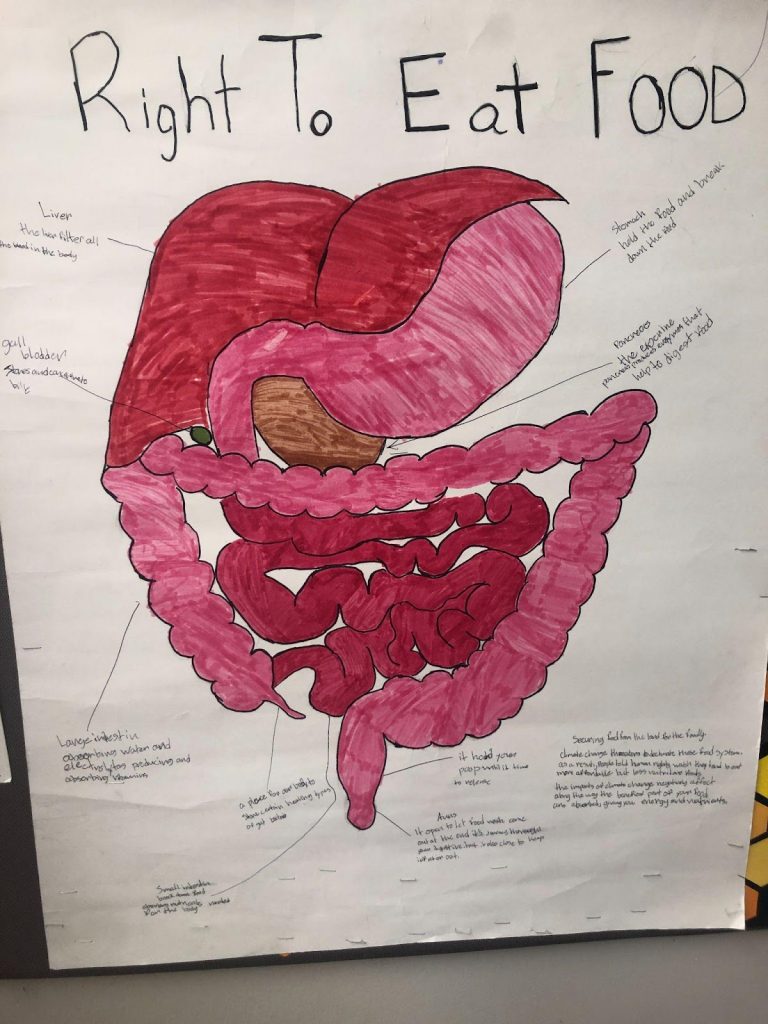

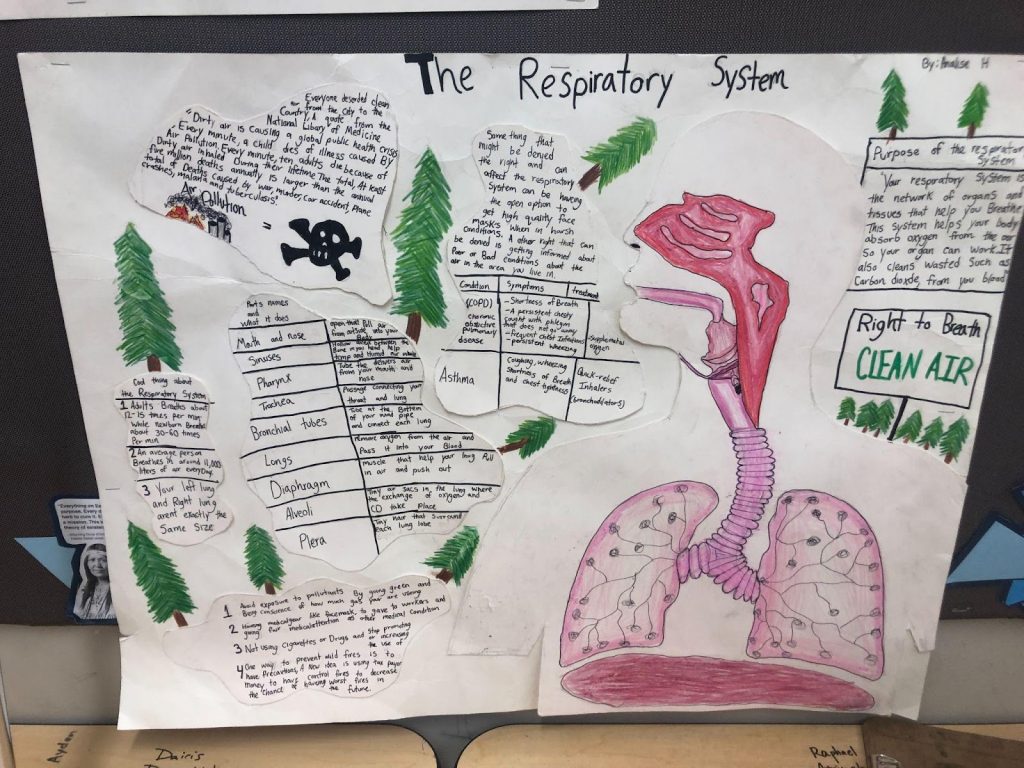

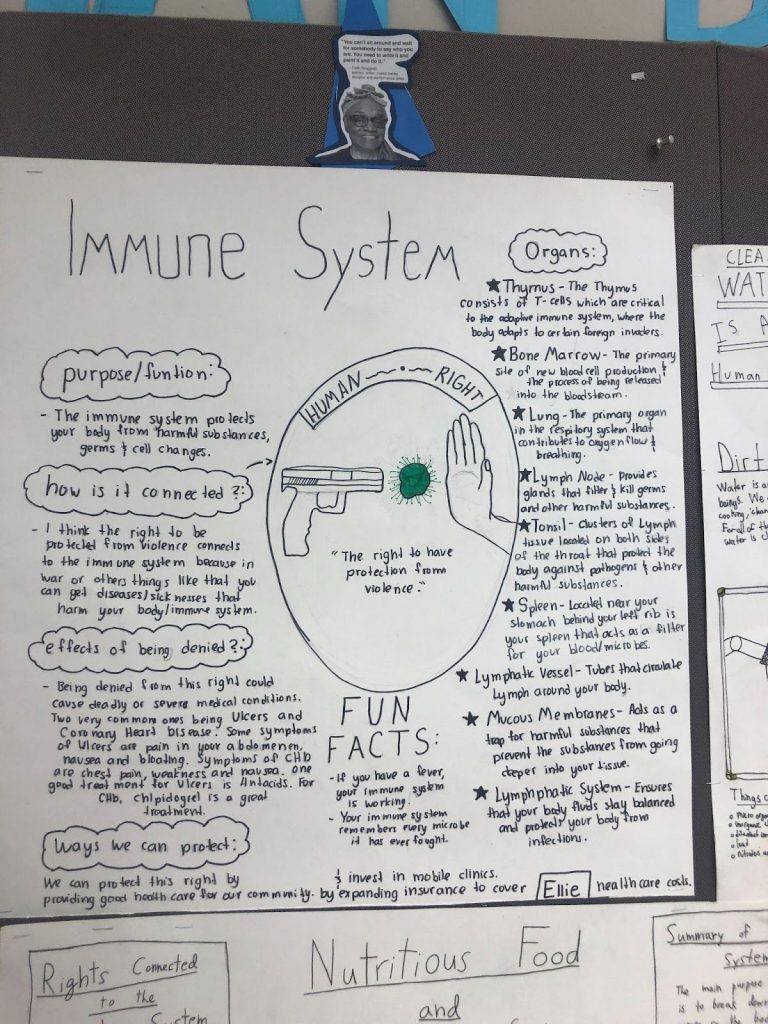

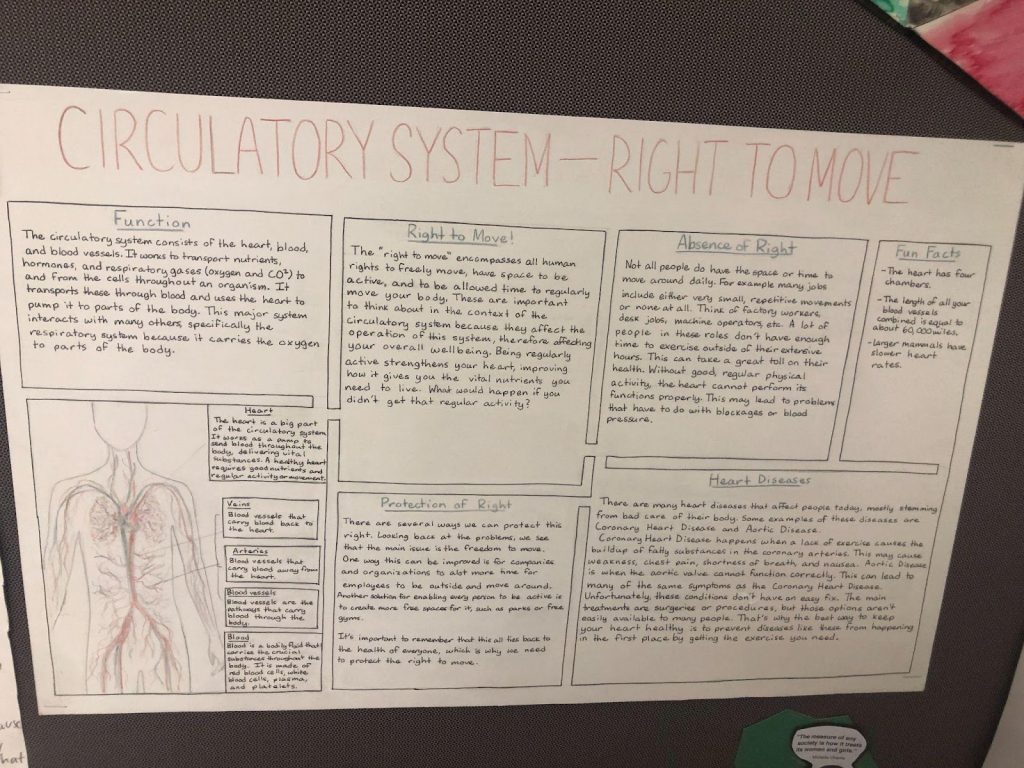

The majority of students chose a poster for this part of the work (see Figure 3a, 3b, & 3c), though most of the choices were selected by at least one student, including a dystopian short story about a future society of chickens that were experiencing many injustices around the denial of trans rights.

Figure 3a. This student linked the right to breathe clean air with the functions of the respiratory system.

Figure 3b. This student assessed the impact of stress caused by violence to the immune system and the right to have protection from violence.

Figure 3c. This student connected the circulatory system and the right to move to highlight how some people’s jobs deny them this right by forcing them into sedentary jobs or ones that only have small, repetitive movements such as factory workers.

Several students made very personal choices in the direction of their project. This included a student whose family had ties to Vietnam wanting to focus on chemical warfare (see Figure 4), a student whose family had immigrated across the US-Mexico border being really interested in the right to food and its links to immigration, and two trans students focusing on rights around bodily autonomy.

Figure 4. Two slides from a student who focused on the impact of chemical weapons on the nervous system and the right of civilians to the International Humanitarian Law, focusing on Agent Orange and the Vietnam War, as well as chemical weapons used today.

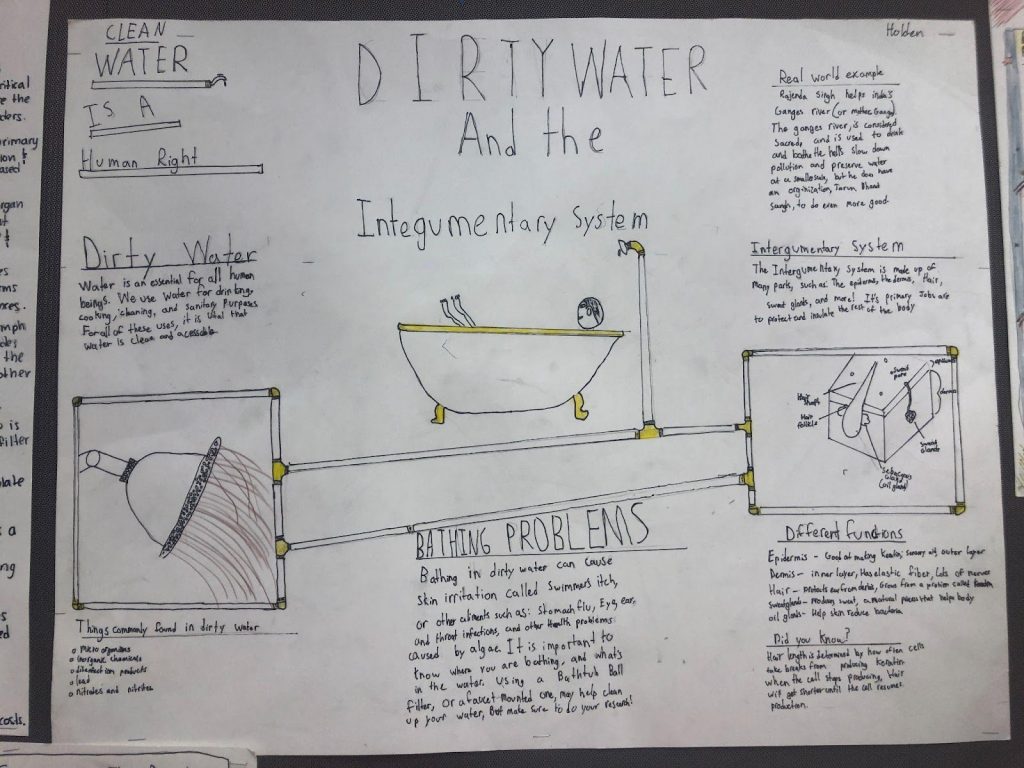

An eighth grader recalled a case study from a short film we watched when he was in seventh grade and pushed himself by choosing a body system not in our curriculum (see Figure 5). Another student who immediately on Day 1 knew he wanted to focus on radiation and radioactive metals did more reading for his project than possibly everyone else combined. Two students, who maybe went less in depth on their projects, learned so many skills on Canva to take going forward.

Figure 5. Though the integumentary system is not part of our curriculum, this student completed extra research and connected this system to the right to clean water, highlighting the work of Rajendra Singh on the Ganges River.

One parent commented during student-led conferences that when her daughter first told her about the project she was honestly confused about the link between human body and human rights. As her daughter was able to pose questions and articulate many of the discussions we had in class her mother became our biggest supporter and was thinking about how she might apply this to her own work with college and high school age young people.

Final Reflections

The inclusion of a text set into a science unit is one that I hope to repeat again this year, and potentially over time build for all my units, even if not utilizing a complex text set for a project like this one. The value of exposing students to new titles, that they might not pick up otherwise, felt valuable as it created connections to the subject matter that I may have not been able to facilitate in our curriculum alone. This especially was true with utilizing picturebooks in a middle school setting, as everyone was able to engage with them, and offered a way to begin engaging in heavy or difficult topics, such as detainment at the border or food insecurity, from the point of view of someone closer to their age.

One of my initial goals for my text set, that I did not get to engage in, was centered around the right to play. The summer I was making my text set, lead was being found in community parks in Durham from incinerators built in the early 1900s, and seemingly linked to health impacts in those communities. Students did interact with one of my main texts of this section during our day of exploring titles (a book called La Calle es Libre/The Streets are Free (Kurusa, 1998), which I only had written in the original Spanish, which allowed students to rely on each other and picture clues to read), and a few students chose this right to focus on- linking it to a variety of body systems impacted by play. However, my original hopes had been to extend into more of a neighborhood study on the topic, utilizing youth participatory action research and oral history to investigate and act on the issue in our community. I think perhaps the individual project combined with this larger group investigation was too big of a goal to fit inside the time constraints of a state mandated curriculum, but I hope in the future to build a different text set out that could pair with community-based student work.

References

Binford, W. (2021). Escucha mi voz/Listen to my voice: Los testimonios de niños detenidos en la frontera sur de Los Estados Unidos. Workman.

Canizales. (2022). Amazona. Lerner.

Dalvand, R. (2023) I Have the Right. Scribe

Kurusa. (1998). La calle es libre. Zaner-Bloser.

Lindstrom, C. (2020). We are water protectors. Illus. M. Goade. Roaring Brook Press.

Ramadan, A. D. (2020) and Ramadan, D. (2020). Salma the Syrian Chef. Annick Press.

Salazar, A. (2022). Land of the cranes. Scholastic.

Holly Hardin is a white, queer, rural Southerner making her current home in Durham, NC as a middle grade educator. Her organizing work in schools has focused on issues of immigrant and racial justice, and she is passionate about abolitionist teaching structures, anti-racist pedagogy, and project-based learning that extends beyond the classroom walls.

Authors retain copyright over the vignettes published in this journal and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under the following Creative Commons License:

WOW Stories, Volume XII, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on by Holly Hardin work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/xii-1/10.

WOW stories: connections from the classroom

ISSN 2577-0551