Navigating Science of Reading Mandates Through a Culturally Responsive Lens

Rosalia Pacheco

As a classroom teacher and now a university literacy instructor, I have found myself juggling literacy initiatives and curriculum mandates. Most recently, the science of reading is a hot topic affecting school district and university reading curriculum. My background as a storyteller and Latina woman caused me to go about this process from a different perspective with an emphasis on infusing culturally responsive practices.

Background: Science of Reading in the Southwestern United States

Most recently, I went through the process of restructuring the reading courses I teach based on required curriculum mandates. Current literacy initiatives in the Southwestern United States are requiring the science of reading and structured literacy approaches in reading instruction. This made sense to me because of my background in special education; specifically, teaching reading skills explicitly using a more diagnostic approach. However, this worried me because I believe many of the instructional models are rooted in behaviorist perspectives rather than a social cultural viewpoint (Stahl, 1997).

In my view, specific strategies to support culturally and linguistically diverse students are often left out of currently used science of reading curriculum and professional development, for example, Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS) training developed by Louisa C. Moats and Carol A. Tolman. I also question the intention of curriculum mandates; for example, the possible use of literacy campaigns, a mass effort to reduce illiteracy, as a way of “centralizing authorities to establish a moral or political consensus” (Arnove & Graff, 1987, p. 2).

My Dilemma

In the Southwestern United States, teachers in districts are receiving professional development training statewide, for example LETRS training. I found some useful information in the LETRS training when I went through it myself. However, I also found there was very little reference to instruction for English learners. In addition, I felt some information that was presented was from a deficit perspective.

Therefore, I was left with the dilemma of restructuring literacy courses to align with the science of reading while building teaching models for supporting diverse learners. To do this, I first investigated available resources on the science of reading for teaching culturally and linguistically diverse students. This area is emerging and there is much work to be done to identify best practices.

I found there have been discussions at the national level about concerns of the recent push toward the science of reading. The National Committee for Effective Literacy (NCEL) raised concerns on the appropriateness of these literacy practices for English learner/emergent bilingual students. In response to these concerns, The Reading League (TRL) and NCEL created a joint statement regarding implementation for English learner/emergent bilingual students that tackled issues such as the importance of oral language and home language development for these learners. A couple of suggestions that were offered in that statement include (The Reading League Summit, 2023):

- Utilizing home language as an asset for literacy development of English

- Use of a variety of culturally and linguistically responsive materials for instruction

Following this research, I was intentional in incorporating the suggestions offered by TRL and NCEL. The following vignettes highlight ways in which I, along with teacher candidates, infused the science of reading curricular mandates into authentic language and literature literacy experiences for students in Southwest.

I teach three reading methods courses for pre-service teachers in the general education teacher preparation program. Because reading courses would be undergoing a teacher prep inspection by the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) and the United States Teacher Preparation Inspection (TPI-US), I was required to update these courses to align with the science of reading and structured literacy tenants. Initially I studied data from other instructors who had taught the reading courses, collaborated with the elementary education program coordinator to get input from clinical supervisors, reviewed previous course syllabi, created aligned syllabi, and updated course texts and materials.

Integrating Culturally Responsive Practices

Because of the specific needs of students enrolled in public schools in the Southwest, I had to ensure that instruction in the courses included opportunities for instructors to clearly model considerations for cultural and linguistic diversity, for example with the use of culturally responsive practices. Culturally responsive practice includes a focus on the student throughout the learning process (e.g., using active methods or including oral language development activities), use of cultural competence (e.g., drawing on experiences, languages, funds of knowledge), and a critical consciousness (Gay, 2002; Grassi & Barker, 2010; Ladson-Billings, 1995). For example, teacher candidates learned about interactive read alouds using culturally relevant texts (González, 1997; Pacheco, 2023) and researched resources for translating literature. However, research on pairing culturally responsive practices with the science of reading is still emerging, making the task more difficult.

I found that although many course texts such as The Teaching Reading Sourcebook (Honig et al., 2019) considered the difference between language structures and the relevance for teaching English, there was very little guidance for pre-service teachers to consider culturally responsive practice paired with the science of reading. Despite the lack of resources, I was able to integrate culturally responsive practices and considerations pre-service teachers could utilize and ponder. Additionally, I modeled the use of hands-on learning such as games like Telephone Pictionary in which students use diagrams to explain key vocabulary and movement like Total Physical Response to act out vocabulary and shape their bodies to represent word definitions.

Personal Experiences & Innovative Teaching Examples

My hope was to create a community of learning in the reading courses where instructional practices could be explored and evaluated with students in mind. Through this process, teacher candidates shared their own experiences of learning to read, as many are English learners themselves. For example, we discussed their memories of learning to read. One pre-service teacher said she did not learn to read until fourth grade because the texts she was reading were irrelevant to her culture. It wasn’t until she was introduced to a book she found relatable that she grew as a reader. Other students discussed being reprimanded for speaking their home language at school. Some teacher candidates shared that they were identified or tested for having a specific learning disability. These discussions were very emotional for some and caused them to reflect on their own practices for teaching reading.

I also shared personal family experiences with reading. My mother did not speak in school until the fifth grade because Spanish was her first language. Teachers thought she could not read or speak. The reason she did not speak is because the administration warned my grandparents that my mother would have to be transferred to a different school if they heard her speaking Spanish.

Valuing Educational Traditions

Based on personal stories, the teacher candidates and I reflected on ways to create a language rich classroom environment that supports multilingualism. In the reading courses I taught, I introduced storytelling paired with literature (de Aragón, 2015; Sauvageau, 1989). When teaching phonological awareness skills, such as rhyme recognition, vocabulary from the story can be used to provide practice of rhyme generation during the retelling. This provides opportunities for students to develop oral language skills during reading instruction which is integral for English learners. Storytelling is an ancient family literacy practice used in communities, specifically Indigenous and Latinx communities throughout the world. I remember my grandfather sitting me on his lap, telling stories, and singing songs in Spanish. These experiences have allowed me to think critically about the instruction I provide, especially reading instruction.

Based on personal stories, the teacher candidates and I reflected on ways to create a language rich classroom environment that supports multilingualism. In the reading courses I taught, I introduced storytelling paired with literature (de Aragón, 2015; Sauvageau, 1989). When teaching phonological awareness skills, such as rhyme recognition, vocabulary from the story can be used to provide practice of rhyme generation during the retelling. This provides opportunities for students to develop oral language skills during reading instruction which is integral for English learners. Storytelling is an ancient family literacy practice used in communities, specifically Indigenous and Latinx communities throughout the world. I remember my grandfather sitting me on his lap, telling stories, and singing songs in Spanish. These experiences have allowed me to think critically about the instruction I provide, especially reading instruction.

My Process

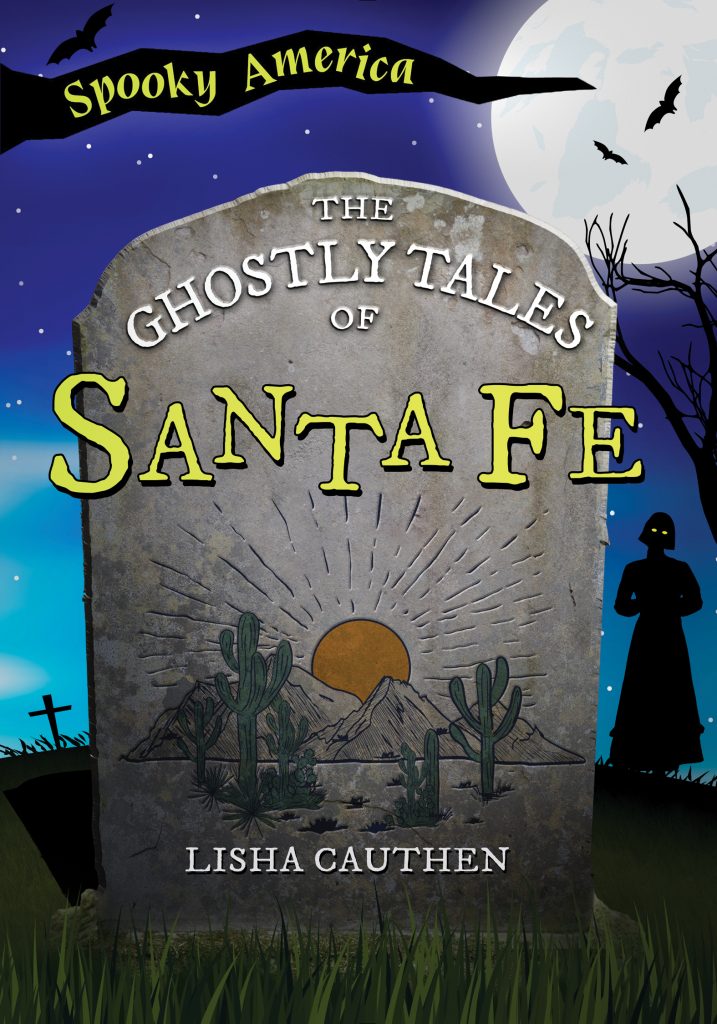

To model the use of storytelling for teacher candidates, I told a story from the book Haunted Santa Fe by Ray John de Aragón (2018). This book is a collection of folk stories with historical overviews in each section. It also incorporates Spanish words and relevant topics known throughout Spanish speaking countries. There is a fourth grade reader version of the book available as well (Cauthen, 2023), which was developed from de Aragón’s book. Using a book with text or words in the language(s) spoken by students makes the books linguistically relevant and meaningful to them, not to mention aligned to the recommendations from the TRL and NCEL statement. It is also a way to make connections between languages and language structures despite mandates of the science of reading instruction.

I began my teaching modeling with explicit instruction on how to identify rhyming words, followed by activities using examples and non-examples. Then, teacher candidates orally generated words that rhymed with the chosen vocabulary from the story. Next, I told the story again with students acting out the parts. During the story re-tell, the rest of the class used body motions to recognize rhyming words as well as generate rhyming words throughout the process. Finally, teacher candidates individually created rhyming words on a worksheet. Rhyming words did not have to be only in English. Following this model lesson, we discussed ways teacher candidates in reading courses could potentially implement the storytelling strategy or a modified version during their student teaching in their individual school placements.

I began my teaching modeling with explicit instruction on how to identify rhyming words, followed by activities using examples and non-examples. Then, teacher candidates orally generated words that rhymed with the chosen vocabulary from the story. Next, I told the story again with students acting out the parts. During the story re-tell, the rest of the class used body motions to recognize rhyming words as well as generate rhyming words throughout the process. Finally, teacher candidates individually created rhyming words on a worksheet. Rhyming words did not have to be only in English. Following this model lesson, we discussed ways teacher candidates in reading courses could potentially implement the storytelling strategy or a modified version during their student teaching in their individual school placements.

Christine’s Vision

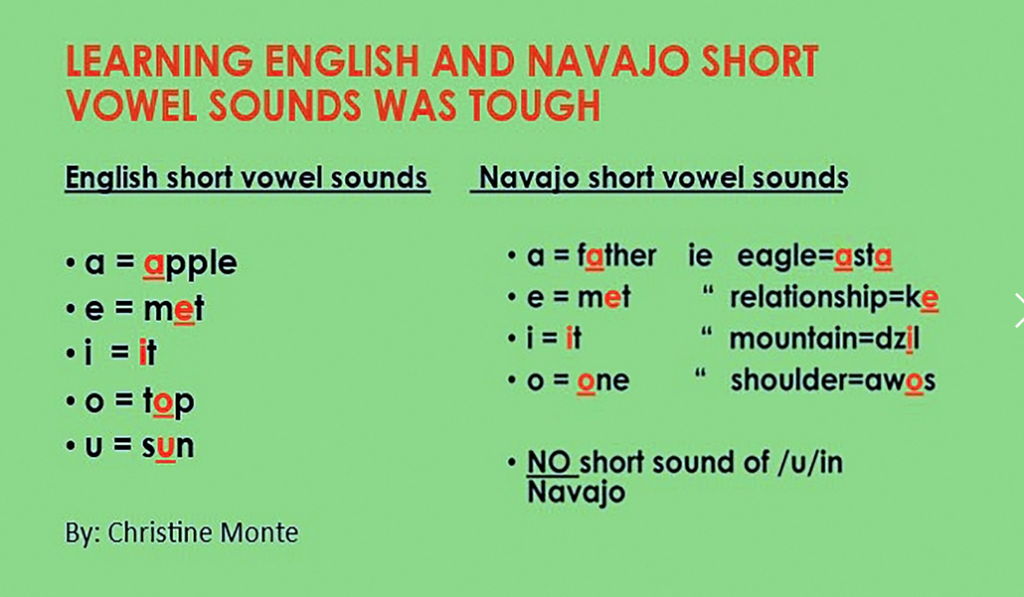

Christine expressed her desire to explore ways to incorporate the Diné language into science of reading instruction, especially because she is a fluent speaker of the language. She was placed in a third grade class in a community school for her student teaching practicum. All nineteen students in her class were Navajo and 85% spoke both Diné and English. Ten percent of the students understoond Diné but could not speak it, while five percent of the students did not understand or speak Diné.

When teaching reading, Christine found that many of the students struggled with phonological awareness foundational skills. Through assessment she found that most of the students particularly struggled with short and long vowel sounds. Also, because Christine is a fluent Navajo speaker, she recognized that she had to make language comparisons when providing vowel sound instruction. Christine made many language considerations for her lesson, for example, Navajo language uses tonal, rising and falling tones, whereas English does not. She had to demonstrate these differences and provide opportunities for students to practice. Students used mirrors when available to make connections with articulation. Additionally, Christine included the instruction that Diné has a four-vowel phonemic vowel system that includes /a, e, i, o/ as compared to /a, e, i, o, u/ in English. She also modeled the nasality, length, and tone as well as variations in Diné not present in English.

Christine carefully planned lessons to teach these skills and make language connections. She went through the process of modeling pronunciations utilizing the I Do, We Do, You Do instructional approach adopted by structured literacy. This approach is like the Gradual Release model that incorporates the process of I do, we do, they do, you do. Christine was also very careful to build on the strengths of the students so that she did not teach from a deficit perspective. She celebrated language variety and diversity in pronunciations. At the same time, she was building knowledge for spelling the words in English. Christine observed that students were making deep connections with language which contributed to their ability to decode and read words in English with this instruction, especially for the Diné speaking students.

Adrian’s Creativity

Adrian was placed in a second grade classroom in an elementary school. Adrian is very artistic and creative in his teaching. He often initiated discussions in class about incorporating hands-on experiences and differentiation when teaching reading skills, especially to incorporate culturally responsive practices for Indigenous students. He planned a lesson based on the Common Core standard we were learning about during a comprehension unit in the reading course, recounting a short sequence of events. Adrian decided to include the hands-on task of following steps to make paper. The paper was used to create a book to recount the sequence of events from the text Neptune and Minerva by Laura Layton Strom (2019). He also connected the content to legends and myths.

Adrian was placed in a second grade classroom in an elementary school. Adrian is very artistic and creative in his teaching. He often initiated discussions in class about incorporating hands-on experiences and differentiation when teaching reading skills, especially to incorporate culturally responsive practices for Indigenous students. He planned a lesson based on the Common Core standard we were learning about during a comprehension unit in the reading course, recounting a short sequence of events. Adrian decided to include the hands-on task of following steps to make paper. The paper was used to create a book to recount the sequence of events from the text Neptune and Minerva by Laura Layton Strom (2019). He also connected the content to legends and myths.

Adrian shared that through progress monitoring, he found that one student progressed tremendously with this lesson. He felt the student was engaged throughout and was able to connect to his own cultural experiences with legends and myths. Adrian expressed that he was able to tap into his personal creativity as an artist, which is very important to him as an educator. The freedom to be creative supported his sense of agency and reminded him of the joy of teaching.

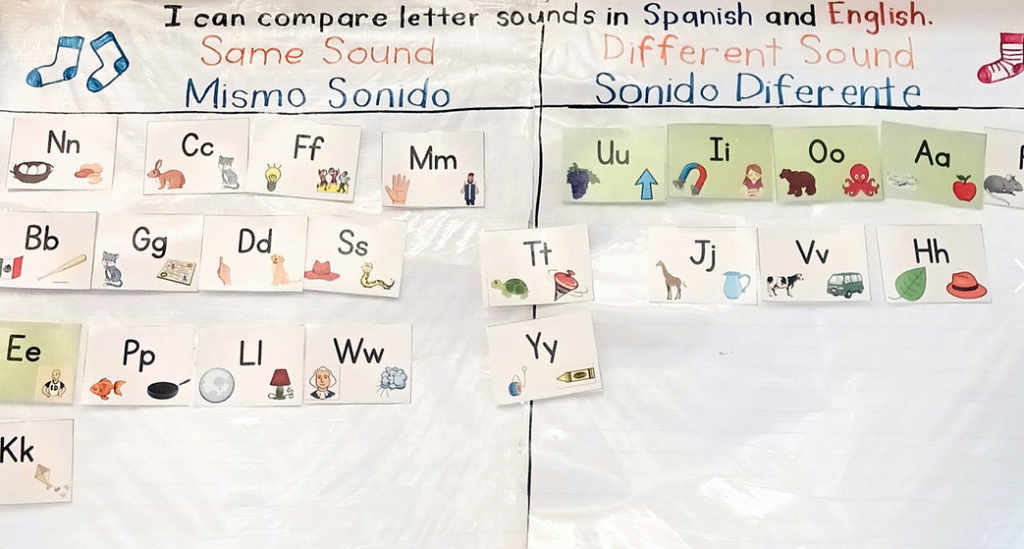

Jeanette’s Engagement

Jeanette speaks both English and Spanish fluently and was placed in a kindergarten dual language school. In her placement, 12 of the 20 students were identified as English learners whose primary home language is Spanish. She planned a lesson to teach letter-sound correspondences. In this lesson she wanted to ensure that students were engaged every step of the way. Jeanette included a great deal of visual supports, games, chants, hand movements, and charts she created to compare English and Spanish. She also created materials and charts to use during instruction.

Before and after instruction, Jeanette assessed student progress. She noticed that students made meaningful growth, especially one student who was provided one-on-one instruction as well. This student had been recently tested by a speech and language pathologist because of concerns of difficulty with communication. Jeanette was ecstatic that the student had progressed significantly with her instruction. She also shared that the experience was highly beneficial in nurturing multilingual practice in tandem with teaching foundational reading skills.

Final Reflections

Although there is much to be done to ensure that instruction based on the current science of reading mandate includes considerations for diverse learners, educators must explore ways to infuse cultural and linguistic responsiveness with explicit teaching of reading skills. It is important that policy makers and curriculum developers focus on these needs purposefully and not just as an afterthought. As a reading faculty in a elementary education teacher preparation program, my journey to better serve students in classrooms will continue.

References

Arnove, R. F., & Graff, H. J. (1987). National literacy campaigns: Historical comparative perspectives. Plenum Press.

Cauthen, L. (2023). The ghostly tales of Santa Fe. Arcadia Children’s Books.

De Aragón, R. (2015). La Llorona. Event Horizon Press.

De Aragón, R. J. (2018). Haunted Santa Fe. History Press.

Gay, G. (2002). Culturally responsive teaching in special education for ethnically diverse students: Setting the stage. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 15(6), 613-629.

González, L. M. (1997). El romance de Don Gato. Scholastic Inc.

Grassi, E., & Barker, H. B. (2010). Culturally and linguistically diverse exceptional students: Strategies for teaching and assessment. Sage Publishing.

Honig, B., Diamond, L., & Gutlohn, L. (2018). The teaching reading sourcebook (3rd ed.). Academic Therapy Publications.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465–491.

Moats, C. M. & Tolman, C. A. (2019). Language essentials for teachers of reading and spelling (LETRS). Voyager Sopris Learning.

Pacheco, H. (2023). Ernesto Joked. Pajarito Chronicles.

U. S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (2022). Digest state dashboard. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved November 29, 2024 from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest-dashboard/state/new%20mexico#characteristicsofpublicschoolstudents%20cite%20apa

Sauvageau, J. (1989). Stories that must not die. Pan American Publishing Co. Inc.

Stahl, S. A., & Hayes, D. A. (1997). Instructional models in reading. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Strom, L. L. (2019). Neptune and Minerva. Newmark Learning.

The Reading League Summit (2023). Understanding the difference: The science of reading and implementation for English Learners/Emergent Bilinguals. Retrieved on November 29, 2024 from https://www.thereadingleague.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/TRLC-ELEB-Understanding-the-Difference-The-Science-of-Reading-and-Implementation.pdf

Dr. Rosalía Pacheco is a Literacy Lecturer III in the Department of Teacher Education, Educational Leadership & Policy (TEELP). She holds an MA and PhD in Special Education with an emphasis on access and inclusion for students who are culturally and linguistically diverse and students with and without disabilities. She is a licensed teacher and taught in NM schools for 11 years including teaching English Language Arts, is LETRS trained, and has experience with intervention in core instruction including reading.

ORCID: 0000-0002-2651-2587

© 2025 Rosalía Pacheco

Authors retain copyright over the vignettes published in this journal and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under the following Creative Commons License:

WOW Stories, Volume XII, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on work by Rosalía Pacheco at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/xii-1/3.

WOW stories: connections from the classroom

ISSN 2577-0551