Exploring Cultural Bridges: Teaching The Kite Runner in the AP Literature Classroom amidst the Discourse of Banned Books

By Jacqueline Gale

Introduction

In a time of post-pandemic disengagement in the English Language Arts (ELA) classroom, there seems to be a growing trend in which teachers feel the need to use excerpts from novels rather than reading them entirely. Navigating the political landscape of book banning, opting to teach excerpts rather than full novels might seem like a more manageable choice, but what is the true cost? In this context, a selective approach to teaching literature not only limits students' exposure to diverse perspectives but also feeds into the broader politicization of banned books (Rodriguez, 2022). Currently, there is a dire lack of representation of LGBTQ+ and BIPOC populations in children's and YA literature. In fact, books that are most frequently banned include those that feature non-white and LGBTQ+ characters or touch on topics such as racism or even health and well-being (Meehan et al., 2024).

Especially for those of us who teach in Title I schools with minoritized populations, it is clear that book bans are dangerous to our students. If there is anything my sixteen years as a senior English teacher has taught me concerning the books I use in my classroom, it is that students don't want to read another book or play from the white canon. I teach at a Title I high school in southern Tucson with a majority Latine population. We also have a considerable number of refugee students from Africa and the Middle East. While I did not have any students from the Middle East in my class last year, I would have loved the opportunity to glean their insights and would fully embrace that opportunity if it came up in the future. Such voices can enrich our understanding of cultures and experiences we might otherwise be unfamiliar with.

While all books have the potential to teach valuable lessons, I have found that my students are far more engaged when they read books by authors from diverse backgrounds. Sherman Alexie's The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, Rudolfo Anaya's Bless Me Ultima, and Alice Walker's The Color Purple are some of the texts that students particularly enjoy. But what I found they enjoy most is almost always Khaled Hosseini's The Kite Runner. The Kite Runner is not only a personal favorite of mine, but I've found it frequently becomes a favorite of students as well. I remember using this book in my class over a decade ago in an on-level senior English class. I had one student who was difficult to motivate to do much of anything. When we started reading The Kite Runner, my biggest difficulty was that he didn't want to do classwork because he couldn't put the book down. It still has a similar impact today.

Whether it's The Kite Runner or any other piece of global literature, it can be helpful to use the Worlds of Words Evaluating Global Literature tool to consider key factors such as literary qualities, the origins of the book, and authorship. This tool also encourages reflection on believability, accuracy, and the authenticity of values portrayed in the text. By examining perspectives, power dynamics, audience, and the book's relationship to others in its genre, we can ensure that the text avoids reinforcing stereotypes or othering. These considerations help promote more nuanced, respectful representations of diverse cultures. Analyzing a book's paratextual features—such as author interviews, historical and political context, and the cover of the book—to gauge an author's cultural connection to the story and intended audience, is a method by Durand et al. (2021) that I also find useful.

The Kite Runner stands up well to both of these tests. This aligns with the proposal by Bishop (2003) that cultural authenticity is defined by how well a book reflects the worldview of a specific cultural group, alongside the authenticating details of language and everyday life. Bishop emphasizes that while no single image can represent a cultural group's life, themes, textual features, and ideologies can help determine authenticity.

The Kite Runner can be a powerful tool for fostering empathy and cultural awareness in the ELA classroom. As one student told me, "...it gives us a different perspective. We're so used to the single story of The Middle East and The Kite Runner shows us there's actually a lot of good there." They tend to hate the main character Amir, early on in the story, and grow to love him by the end, realizing that he is a human who makes mistakes but grows from them. This book teaches that redemption is possible no matter what sins have been committed. The young adults I have the privilege of working with value this story although I sometimes hear statements like, "Man I hate this book- when is Amir going to get what he deserves?" Others, like a senior I had this past Spring, have said things like "his book was intense, but it teaches lessons I needed at this point in my life." Engaging with The Kite Runner is undeniably worth it.

While The Kite Runner is an incredible tool to foster empathy and cultural awareness in the ELA classroom, teachers should be mindful that it frequently appears on banned and challenged book lists. According to the American Library Association (ALA), it was ranked 50th among the 100 most frequently challenged books of the 2000s (American Library Association, 2013). Before teaching this or any challenged book, educators may benefit from exploring resources to help navigate potential challenges. In addition to ALA, resources like Unite Against Banned Books, which offers book summaries and tools to report censorship attempts (Unite Against Banned Books, 2024), and PEN America, which provides guidance for taking action against censorship and banned books (PEN America, 2024) can be helpful.

Obtaining Parent Permission

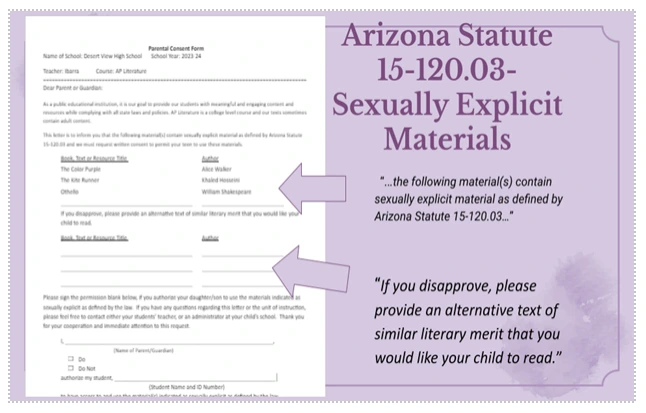

In light of recent Arizona legislation around the content of books teachers use in class, it is helpful to be aware of what state laws say and how to avoid breaking them before teaching this or any book. First, Arizona Statute 15-120.03 (2023) prohibits the use of any books or materials that can be deemed sexually explicit. An exception can be made if the materials have high educational value/literary merit, written parent consent is attained before using the material, and finally, alternate materials have to be made available to any students whose parents do not consent. Initially, when this law with vague wording went into effect I remember how quickly teachers mourned the books they could no longer teach at the recommendations of scared district officials. In hindsight, all we had to do was learn how we could continue to teach them.

What I have learned to be the easiest method of obtaining permission to read anything that might be considered sexually explicit is to send home a parent permission slip at the beginning of the school year with all the books I plan to teach each semester. One way this is helpful is that I don't have to worry about obtaining permission multiple times. To keep things simple, I state "This letter is to inform you that the following material(s) contain sexually explicit material as defined by Arizona Statute 15-120.03 and we must request written consent to permit your student to use these materials." I then list the books we'll read and provide a space where a parent can write in an alternate title of similar literary merit if they disapprove. If a parent felt they were unable to do this, I provided some alternative titles.

Because I transparently discuss the book's contents with students, they know why these texts are challenged or banned and I ask them to first decide for themselves if they will be comfortable reading these texts before requesting parental permission. I don't want to jinx anything, but so far, I have yet to have a single student read an alternate text because I have consistently earned 100% approval from all parents and guardians. The one time I did receive a "no" for an answer a student reported back that his mom was concerned about him reading a scene that included sexual assault. I asked his mom if she would be willing to read the scene for herself and then decide if she wanted her son to sit it out or not. After she read it and he reported back to class he shared, in his words, "She read it and she was like 'yeah, whatever.'" And he turned in the form with her signature giving approval.

Engaging Students with The Kite Runner

After obtaining parental consent, I begin teaching The Kite Runner by providing essential background on Sunni and Shia Muslims, as well as the discrimination faced by the Hazara people at the hands of the dominant Pashtun ethnic group. To help students grasp the historical and theological distinctions, I use the Council on Foreign Relations' video An Overview of the Sunni-Shia Divide (2023), which explains that Shias believe in Ali and his descendants as part of a divine lineage, while Sunnis oppose political succession based solely on Mohammed's bloodline. This foundational understanding is critical, as the novel's ethnic and religious divide underpins much of the story's conflict. Specifically, the predominantly Sunni Pashtun community's oppression of the Shia Hazaras mirrors broader systemic inequalities.

To further explain these ethnic differences, teachers might find Bhushan's (2022) work on ethnic dehumanization in the novel particularly helpful for building their understanding of the religious and ethnic complexities portrayed in the text. Introducing students to Khaled Hosseini's official website (Hosseini, 2024) allows them to learn about the author's personal experiences in Afghanistan, which shaped the narrative. Given that American students may be unfamiliar with competitive kite running, I also share the Al Jazeera English video, Viewfinder: The Real Kite Runners (2007). This video not only introduces the sport but also provides a cultural context that students find engaging.

My students range from 16-18 years old, but one surprisingly small gift I offer that lights up their eyes and gives me a glimpse into the child within is giving them a handcrafted bookmark to use in their copy of the book (see Figure 2). I am surprised at how many of them are still using their bookmarks by the end of the story. I recommend other teachers try this as well or consider giving students the opportunity to create their own bookmarks before beginning the reading.

Classroom Discussions and Activities

We start by reading aloud collectively in class. Students enjoy moving around the room, with each person reading at least one paragraph but having the option to read more if they wish. They are always pulled in when they hear the line right in the beginning, "There's a way to be good again" (Hosseini, 2003, p.2). I vary our reading routines to maintain this initial engagement, especially during more intense chapters. For scenes that might be uncomfortable, silent reading works well—it's also rewarding to hear their audible gasps or see their reactions as they read. Other times, students enjoy reading aloud in small groups, which fosters collaboration and discussion. For group work, I enjoy utilizing reading protocols such as Colorín Colorado's Collaborative Reading Protocol (Colorín Colorado, 2023). Before beginning a challenging chapter, I always provide a content warning and invite any students who feel uncomfortable to sit out. While no one has made this request yet, I believe it's essential to offer this option. Changing the environment can also enhance the reading experience. On pleasant days, I might take the class outside or to the library, where students make themselves comfortable, listen to calming music, and immerse themselves in the story. I've found that mixing up the methods and settings for reading the book keeps students engaged and helps them stay invested as we work through the entire book together.

To support students' engagement with The Kite Runner, I strive to create varied reading environments and approaches that keep them comfortable and open to its challenging material. When we encounter difficult scenes—such as Amir witnessing the violent assault of Hassan by Assef and failing to intervene—it becomes crucial to foster opportunities for deeper reflection and discussion. This pivotal moment in the text is ideal for a Socratic seminar, where students can engage in meaningful dialogue with one another.

Scott Filkins' strategy guide on Socratic seminars offers practical methods for facilitating student-centered discussions that promote critical thinking and deeper understanding (Filkins, n.d.). Before the seminar, I review the concept of literal, interpretive, and universal questions with students. They then write their own level two (interpretive) and level three (universal) questions about the chapter. A useful resource for this process is the document Levels of Questions: Literal, Interpretive, Universal (Bowman at Brooks, n.d.), which provides clear definitions and examples of these question types. After writing their questions, students add them to a shared Google doc and vote on their top picks by placing an “x” after the five questions they most want to explore. I give them time to explore these questions and ask them to find helpful quotes in the text to inform their responses so they are adequately prepared for the seminar. I find that this preparation helps them to feel informed and less nervous to share in a group discussion.

Most importantly of all, the Socratic seminar allows them to ask and make sense of the issues that come up for them at this point in the story and it creates a safe place to share feelings they have about it. While some students ask questions like, "Why does Baba favor Hassan over his own son?", others want to know "How could Hassan be so loyal to Amir even after Amir betrays him?", or "What other examples of betrayal have we come across in literature before?" Students do not need me to provide them with discussion—they know what they want to explore and it is simply my responsibility to create the space for it.

Additionally, I use reading guides to help ensure students understand key events and details of the text and are keeping up with the pacing. One I have found helpful is the Penguin Random House Education teacher's guide for The Kite Runner, which includes helpful vocabulary, relevant themes, questions for students, and more. Because I teach this book in AP Literature currently (but it works well with on-level classes too), I also give students a periodic AP Literature Open Response essay prompt for test preparation. In AP Literature, students are expected to do the equivalent of running a marathon in writing three essays in 120 minutes when they take the AP exam. One of these essays, the “Free Response” provides a prompt to which they are to respond using a work of literary merit of their choice (not surprisingly, many students chose The Kite Runner). College Board provides a valuable resource for AP exam preparation, including past exam questions for analysis that date back to 1999 (College Board, 2024). Between Socratic seminars, study guide questions, and discussions on themes that come up in The Kite Runner, students develop a well-rounded understanding of the book.

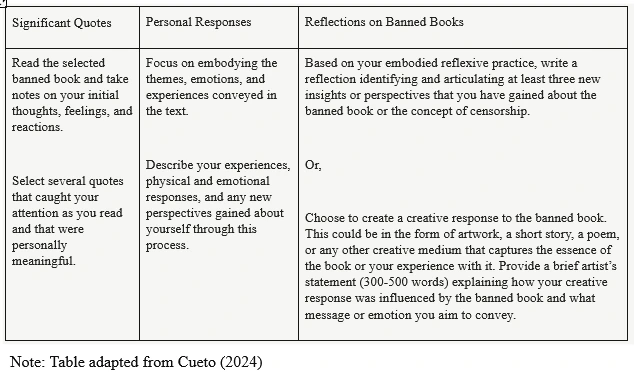

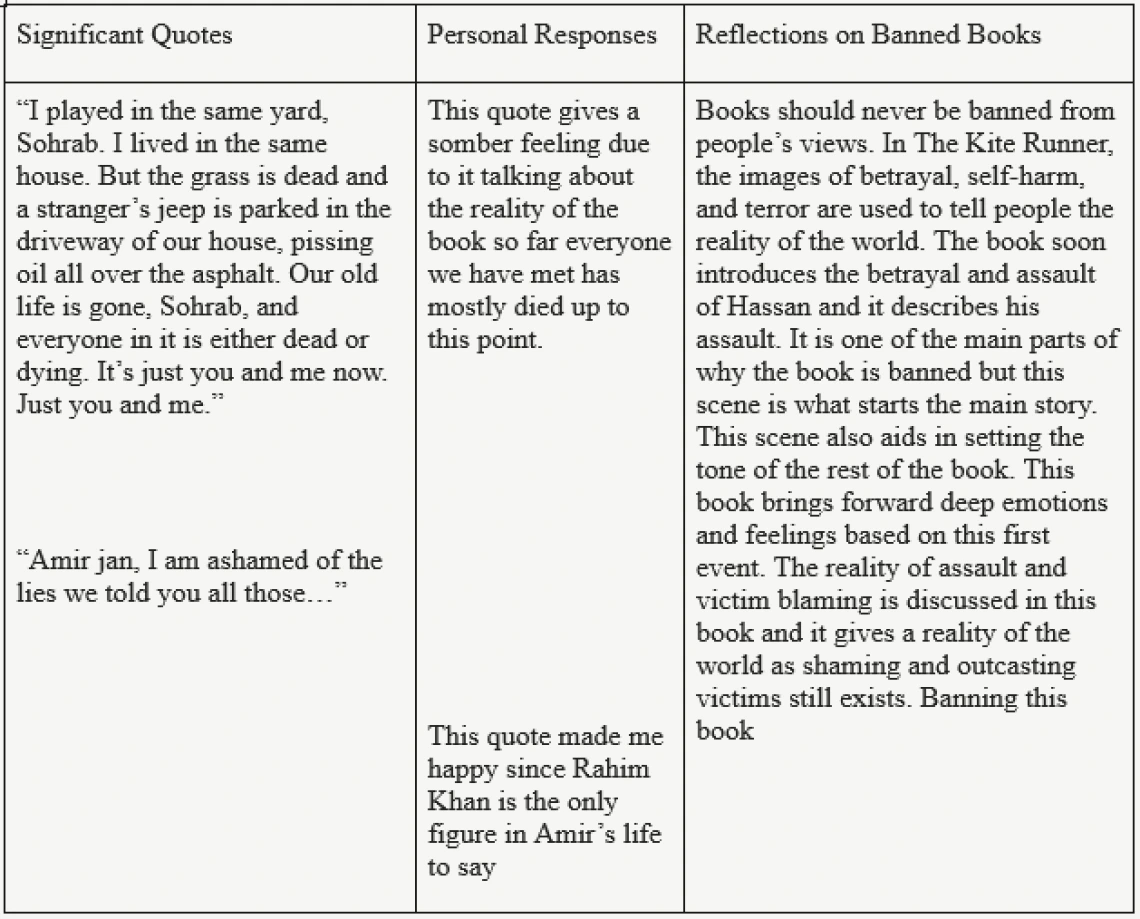

While I aimed to help students develop a well-rounded understanding of The Kite Runner, I also wanted to offer them a creative outlet for personal expression. To achieve this, I introduced a new method of reflection I learned in a class at the University of Arizona around the Embodied Reflexive Response (Cueto, 2024). This method utilizes a three-column chart where the first column is used for key quotes in the text, the center column is used for embodied responses to the text (paying attention to physical and emotional responses to the text while reading), and the final column is used for either an essay about the book that includes insights gained on censorship or an artistic response that includes an artist's statement. This final column is used for their final project and is not to be completed until we finish reading the book.

Through first engaging in this type of reflection as a student myself, I realized the effectiveness of multimodal options to engage in deep critical thinking as demonstrated by myself and my classmates, and couldn't wait to bring this practice to my classroom. What students did with the opportunity to engage in creative reflection went beyond anything I could have imagined, highlighting how multimodal options foster students' critical reading and thinking skills. As noted by Coppola (2020). "The only true requirements for redefining writing to include multimodal forms of composition are desire, imagination, and—most importantly—a willingness to take a healthy risk" (p. 70). Students were definitely excited to take it.

Reader response theory, which emphasizes the unique experiences, perspectives, and interpretations that students bring to a text, aligns well with multimodal reflection. By valuing students' engagement with texts, reader response theory encourages an active dialogue between reader and text, fostering deeper connections and critical insights (Woodruff & Wilson, 2013). Doing Critical Literacy by Hilary Janks and colleagues (2014) is a valuable resource for integrating critical literacy into classroom practice, as it emphasizes the interplay between language, power, and identity. It provides practical strategies for guiding students to move beyond personal interpretation and examine the broader social and cultural contexts that shape texts and their meanings.

Student Embodied Reflexive Responses

Once it was time for students to complete their Embodied Reflexive Response Journals, they had time to reflect on their entries and decide on a creative, multimodal project to demonstrate their deeper learning while reading The Kite Runner. They presented these projects to their classmates. Below are pictures of some student responses, along with their explanations of them (pseudonyms have been assigned to protect their identities).

Amy's project is a painting of water ripples, symbolizing the transformation of Amir from a timid boy to a courageous man in The Kite Runner. She believes that everyone inherently possesses goodness but sometimes needs time for clarity and reflection, akin to waiting for water to settle. The middle of the ripples represents Amir's actions throughout the story, while the outer ripples symbolize his confrontation with his past. Amy sees Amir's journey as analogous to the calming of water after disturbance, suggesting that redemption is possible despite past mistakes.

Alexa aimed to convey her emotions of sadness and hope through an art piece, symbolized by a growing plant. Additionally, she incorporated a message about perception, illustrated by a boy painting over an ugly picture and tearing a cover back to reveal truth. The inclusion of buttons from Coraline, one of her favorite movies, served as a personal reference to choices and consequences.

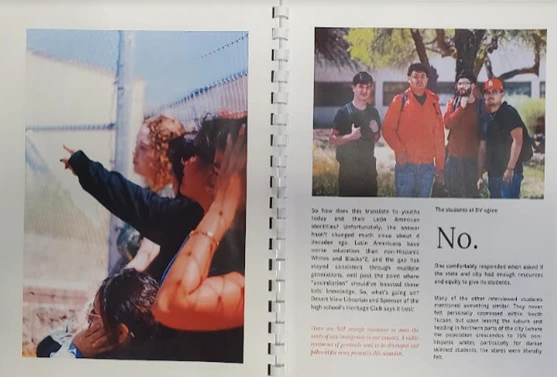

Franky, intrigued by the discrimination Amir and his father faced upon moving to the United States, was interested in comparing the Afghani experience of immigration to those of Mexican Americans. He conducted research amongst his peers about their experiences with discrimination based on race and ethnicity, interviewed a teacher who had personal experience with the unfair demands of applying for citizenship, recorded and transcribed it, and then proceeded to check out a camera from the photography teacher to take his own pictures to create a magazine.

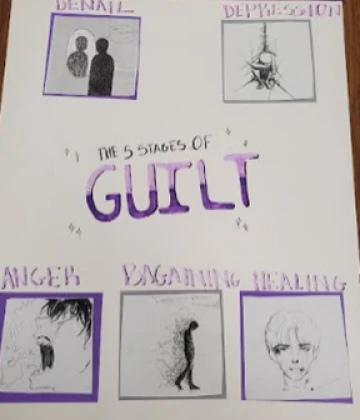

Julie created a poster to reflect Amir's development over the course of the book when she realized during the reading that Amir's character went through the five stages of guilt. She gave a presentation in which she explained what he was going through at each stage and ended with a positive note about his brighter future ahead.

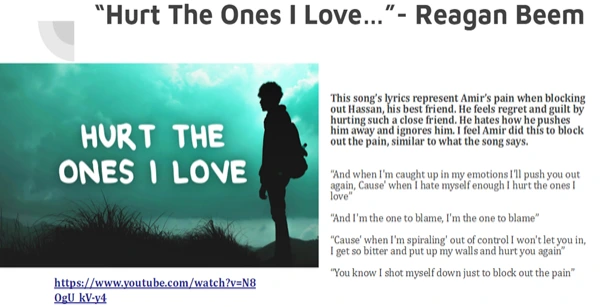

Elias created a playlist for Amir's journey throughout the book. He created a slideshow with several slides and engaged in literary analysis of both The Kite Runner and song lyrics. Many of the songs on his playlist were new songs to him that he found through his research. He provided a rationale for each, a link to the music video, and the lyrics that stood out to him in each song.

An excerpt from Samantha's essay response provides her thoughts on censorship and book banning. In it, she delves into the reasons why this book is needed in the classroom, making connections to oppression and discrimination that exist in her own communities today. Also... she's the same student I referenced earlier, who claimed she hated the story.

These projects demonstrate the power of choice in final projects, allowing students to draw on their funds of knowledge–the lived experiences, cultural practices, and personal interests they bring to the classroom–to reflect on and process new learning (Moll, Amanti, & Gonzalez, 2005). By engaging with The Kite Runner through creative and analytical responses, students found meaningful ways to demonstrate their knowledge. Alexa's art piece, Franky's investigative magazine, Amaris' poster analysis, Elias' playlist, and Sam's essay are all testaments to how reader response theory and critical literacy can empower students. These approaches encourage students not only to engage deeply with the text but also to connect its themes to their lives and communities, fostering critical thinking and empathy.

Conclusion

It may not be "easy" to teach banned books in the classroom, but I believe students' work speaks for itself. Not only do students have the opportunity to engage in rich conversations about delicate yet important issues, but they actually look forward to reading and learning what comes next. Students particularly enjoyed having new insights about the Middle East and also felt some appreciation for the safety they have in the United States upon learning about the Taliban. Despite Amir's experience of leaving his home country for safety, the memories of the childhood he depicted gave students an alternate lens they were grateful for, one of a positive image. The only "extra" work teaching The Kite Runner or any banned book really creates for me is in getting parent permission and being committed to creating a safe space to address serious feelings that come up around delicate issues, many of which are relatable. Students, I anticipate, will remember The Kite Runner, and the lessons it offers for a lifetime.

Resource Ideas

Something I want to do when I teach this book again is explicitly teach reader response theory. As Appleman (2023) shares, "I simply didn't want to encourage my students to respond to literature within a classroom context that was never articulated; I wanted to teach them about the theory of reader response and then encourage them to respond to literary texts with those responses enriched by their metacognitive awareness of that theory" (p.35). By making reader response theory a central part of the curriculum, I hope to deepen students' engagement with texts and encourage critical thinking through both personal reflection and theoretical understanding.

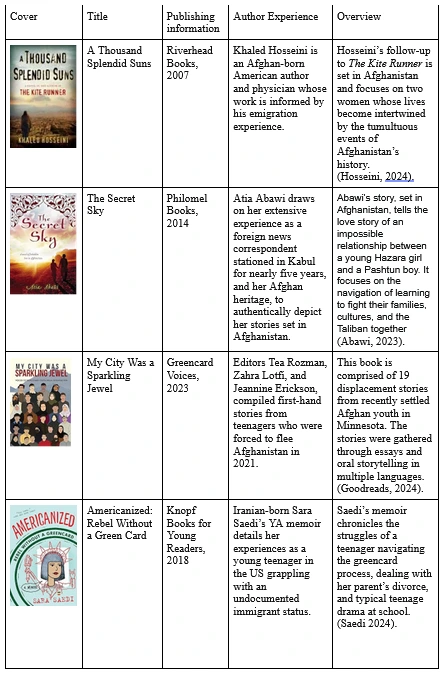

In addition, when I teach this unit again, I would like to offer more multimodal texts that support students' learning about Afghanistan, the Taliban, and the broader socio-political context in which The Kite Runner is set. For example, short documentary videos, interviews with people from Afghanistan, and supplementary YA novels could help students engage with the text from multiple angles, enriching their reading experience. In the table below (Table III) I have created a table of books that could be helpful for students wanting to expand their understanding of the Middle East. I have elected to include relevant paratextual features, again, drawing on the methodology proposed by Durand et al (2021).

Finally, at the end of the AP class, I would love to have students reflect on which book they learned to appreciate the most and why. This reflection could serve as evidence of their learning journey and how their understanding of complex issues, such as identity, power, and conflict, has evolved. A self-evaluation tool might also be a useful addition to this process. In this self-evaluation, students could reflect on their growth as critical readers and thinkers, as well as how their responses to literature have changed over the course of the school year.

I understand and appreciate that teaching a banned book might intimidate some teachers, especially if they are new to the field or work in a state with strict laws. In sharing my story of teaching The Kite Runner with colleagues at my school, I have been able to alleviate some concerns by sharing resources, and I have also been able to reassure them that it's worth the effort it takes to teach them. The levels of critical thinking and engagement demonstrated by students' projects easily exemplify this. One teacher shared his apprehension of teaching The Absolutely True Diary of a Part Time Indian with me. While he had heard nothing but positive praise for it and was excited to teach it he decided to avoid it altogether. Upon sharing this article with him, he realized that it would have been less work to obtain parent permission than it was for him to teach a text even he and his students loathed reading. I am grateful for his feedback, as he has inspired me to share these findings and practices with other fellow educators, and I hope anyone reading this article might feel empowered to teach the books our students need.

References

Abawi, A. (2023). About Atia Abawi. Retrieved November 27, 2024, from https://www.atiaabawi.com/bio

Adichie, C. N. (2009, July). The danger of a single story . TED. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D9Ihs241zeg

Al Jazeera English. (2011, January 15). Viewfinder: The real kite runners . YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i5S47aSlezs

Appleman, D. (2023). Critical encounters in secondary English: Teaching literary theory to adolescents (4th ed.). Teachers College Press.

American Library Association. (2013). Frequently challenged books of the 21st century. ALA. https://www.ala.org/bbooks/frequentlychallengedbooks/decade2009

Arizona State Legislature. (2023). Title 15 §120.03. https://www.azleg.gov/viewdocument/?docName=https://www.azleg.gov/ars/1…;

Bhushan, V. (2022). Ethnic dehumanization in Khaled Hosseini's The Kite Runner. The Creative Launcher, 7(6), 84–92. https://doi.org/10.53032/tcl.2022.7.6.09

Bishop, R. S. (2003). Reframing the debate about cultural authenticity. In D. L. Fox & K. G. Short (Eds.), Stories matter: The complexity of cultural authenticity in children's literature (pp. 25–40). National Council of Teachers of English.

Bowman at Brooks. (n.d.). Levels of questions: Literal, interpretive, universal. https://bowmanatbrooks.weebly.com/uploads/8/3/8/3/8383240/levelsofquest…;

Colorín Colorado. (2023). Collaborative reading protocol. Retrieved November 25, 2024, from: https://www.colorincolorado.org/teaching-ells/ell-classroom-strategy-li…;

Coppola, S. (2020). Writing, Redefined : Broadening Our Ideas of What It Means to Compose. Routledge.

College Board. (2024). AP English Literature and Composition past exam questions. AP Central.

Council on Foreign Relations. (2023, April 27). The Sunni-Shia divide. https://www.cfr.org/article/sunni-shia-divide#:~:text=Shias%2C%20a%20te…% 20stems,succession%20based%20on%20Mohammed's%20bloodline

Cueto, D. W. (2024, January 16). Banned Books and the Politicization of Schools and Libraries Syllabus. Tucson; University of Arizona.

Durand, E. S., Glenn, W. J., Moore, D., Groenke, S. L., & Scaramuzzo, P. (2021). Shaping immigration narratives in young adult literature: Authors and paratextual features of USBBY Outstanding International Books, 2006–2019. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 64(6), 665–674. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.1149

Filkins, S. (n.d.). Socratic seminars. ReadWriteThink. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://www.readwritethink.org/professional-development/strategy-guides…;

Goodreads. (2024). My city was a sparkling jewel by Maya Khosla. Retrieved November 27, 2024, from https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/126132470-my-city-was-a-sparkling-j…;

Hosseini, K. (2024). Official website of Khaled Hosseini. https://khaledhosseini.com/

Janks, H., Dixon, K., Ferreira, A., Granville, S., & Newfield, D. (2014). Doing critical literacy: Texts and activities for students and teachers. Routledge.

Meehan, K., Magnusson, T., Baêta, S., & Friedman, J. (2024). School book bans: The mounting pressure to censor. PEN America. Retrieved May 10, 2024, from https://pen.org/report/book-bans-pressure-to-censor/

Moll, L. C., Amanti, C., & Gonzalez, N. (2005). Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practices in households and classrooms. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Penguin Random House Education. (n.d.). The Kite Runner teaching guide. Penguin Random House. Retrieved November 27, 2024, from https://images.penguinrandomhouse.com/promo_image/9781594631931_8190.pd…;

Rodríguez, R. J. (2022, October 21). Even banned books open minds. National Council of Teachers of English. https://ncte.org/blog/2022/10/even-banned-books-open-minds/

Saedi, S. (2024). Sara Saedi: Author, screenwriter, TV writer. Retrieved November 27, 2024, from https://sarasaediwriter.com/

Unite Against Book Bans. (n.d.). Unite Against Book Bans. American Library Association. https://uniteagainstbookbans.org/

Woodruff, A. H., & Griffin, R. A. (2017). Reader response in secondary settings: Increasing comprehension through meaningful interactions with literary texts. Texas Journal of Literacy Education, 5(2), .

Jacqueline Gale is a high school English teacher, PhD student, and advocate for educational equity. A proud first-generation college graduate from South Tucson, she now teaches at her alma mater, Desert View High School, and is pursuing a PhD in Teaching, Learning, and Sociocultural Studies at the University of Arizona.

ORCID: 0009-0006-6187-7910

© 2025 Jacqueline Gale

Authors retain copyright over the vignettes published in this journal and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under the following Creative Commons License:

WOW Stories, Volume XII, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on work by Jacqueline Gale at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/xii-1/5.

WOW stories: connections from the classroom

ISSN 2577-0551