by Yoo Kyung Sung, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM

“Russian children’s literature and culture are obscure subjects in the West. When they come up in a conversation, even the most Russia-savvy students shrug their shoulders and produce a genuinely puzzled look on their faces “ (Balina & Rudova, 2008, p.xv,)

Earlier I looked at two books, Breaking Stalin’s Nose and Arcady’s Goal, set in repressive Stalinist Russia. I then introduced The Family Romanov: Murder, Rebellion & the Fall of Imperial Russia, an informational text describing the establishment of the Soviet Union. In doing so I developed a real curiosity about the development of children’s literature written in Russia. Balina & Rudova (2008) describe the traditional global literary Russian icons as the Nutcracker, Baba Yaga, and Ivan the Fool. Balina and Rudova (2008) note, “But hardly any would be familiar with the many popular children’s tales from Soviet times.” (p. xv).

What is true, even now, is that children’s books are often written and published in political and cultural contexts. For children, those influences were everywhere. As a South Korean child, I came to realize that political propaganda was frequently embedded within otherwise child friendly materials. As I thought about writing for WOW Currents this month, I recalled my school art classes where creating posters and paintings with politically appropriate slogans were encouraged. Since North Korea was the enemy, many of these featured references to neighborhood safety and reminders to be alert for North Korean spies. As an enemy, North Korea held an unusual fascination for me as I watched animation films of righteous South Korean boys fight courageously against the North Korean army and its leaders, often depicted as beastly creatures. That genre was so vividly painted in my memory that I still recall much of it clearly today. Leaders are clearly capable of instilling political biases in unaware young children through literature they provide and children happily consume.

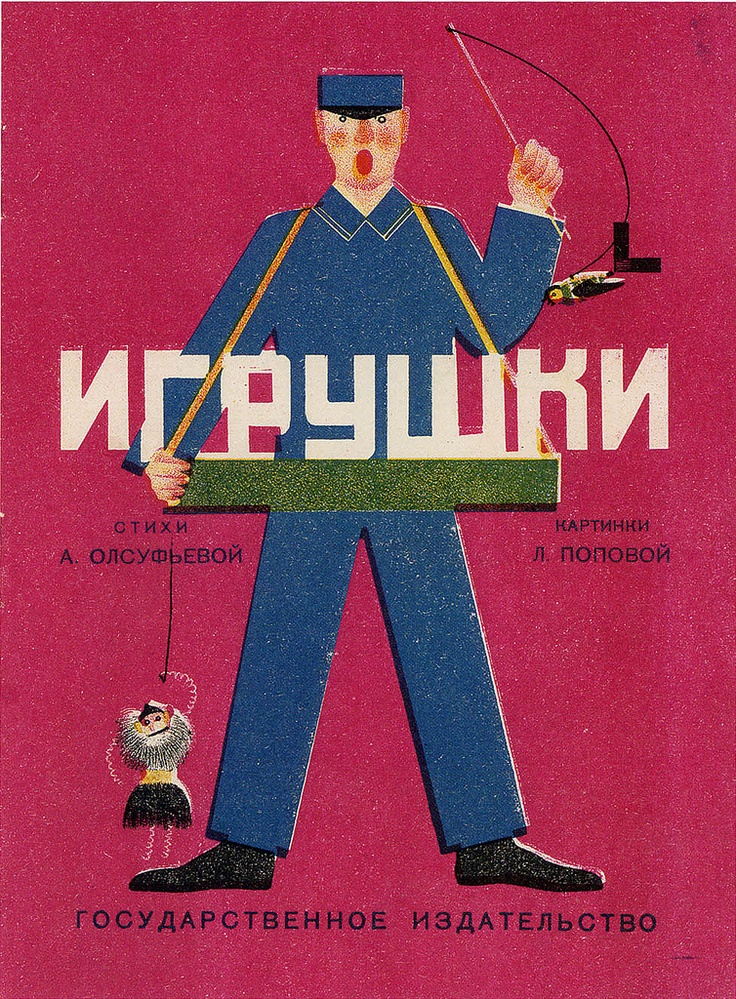

There is an interesting parallel when Russian children’s literature is viewed through this lens. Voskobinikov (2013) notes the pendulum of Russian children’s literature was driven in more mature directions as adults’ interests forced their way into children’s lives. Such collective national propaganda controls, “the states’ appropriation of childhood,” were intended to create a “bright future” (68). In the 1920’s and 1930’s the Russian population’s literacy rate was as low as 35% (Shin, 2008). Children had limited access to reading materials within a learning environment not at all as supportive as other European countries. In the 1920’s the Soviet Union produced large amounts of picture books to be mass distributed to labor camps, day cares, and schools. Pre-Revolutionary literature with positive connotations was eliminated as “ideologically corrupt” (Balina, 2008, p.92). Picture books were created for the express purpose of creating a new, communist nation and book publishing focused on quantity over quality. Ironically, the low budget picture book industry gave birth to aesthetically beautiful avant-garde art and design excellence in super-realism and structuralism (Shin, 2008). 1920’s Russian children’s books were differentiated from other European picture books as Russian books avoided “childlike” or “innocent” stories and depictions in favor of realism. Shin (2008) notes the Soviet Union in 1920’s was an era of picture book prosperity as the new nation building ideology encouraged different artistic visions of a new nation despite the ever-present harsh living conditions. Within ten years, picture book development went downhill as ideology based censorship began to rigidly control the contents of picture books.

The Korean picture book magazine, Story of Picturebooks, interviewed Tayo Shima who was a former IBBY (International Board on Books for Young People) President in 2008. She selected works from two important Russian writers of the era. One of them vanished and one of them committed suicide. The magazine doesn’t specify which fate befell which one. We can say, however, their lives ended tragically. Feel free to speculate, as many have, on whether or not they ran afoul of the Stalinist regime. You can peruse some of these old Russian picture books here.

The Korean picture book magazine, Story of Picturebooks, interviewed Tayo Shima who was a former IBBY (International Board on Books for Young People) President in 2008. She selected works from two important Russian writers of the era. One of them vanished and one of them committed suicide. The magazine doesn’t specify which fate befell which one. We can say, however, their lives ended tragically. Feel free to speculate, as many have, on whether or not they ran afoul of the Stalinist regime. You can peruse some of these old Russian picture books here.

Overall, U. S. educators have limited access to Russian picture books.  More readily available in the U. S. (and in English) are Forest Homes by Mai Miturich (1988) and The Icicle by Valery Voskoboinkov (2007). Dorothy and the Glasses by Ivona Brezinova (Russian/2007), The Gift of Joy and Laughter by Valentina Illiand (2011), and To Have a Dog by Ivona Brezinova (2007) are also available through internet book stores.

More readily available in the U. S. (and in English) are Forest Homes by Mai Miturich (1988) and The Icicle by Valery Voskoboinkov (2007). Dorothy and the Glasses by Ivona Brezinova (Russian/2007), The Gift of Joy and Laughter by Valentina Illiand (2011), and To Have a Dog by Ivona Brezinova (2007) are also available through internet book stores.

Different editions in multiple Eastern European languages, Russian, and Ukrainian are available. These may be useful for ESL teachers who work with Russian-immigrant populations in their communities. These books are notable not just because they are in Russian, but because they are contemporary childhood stories. Immigrant children may find their own stories or connections in books that go beyond the Baba Yaga world.

References

Balina, M., & Rudova, L. (2008). In Balina M., Rudova L. (Eds.), Russian children’s literature and culture. New York: Routledge.

Present & Correct. (January 25, 2013). 15 old Russian Children’s books.. Retrieved from http://www.presentandcorrect.com/blog/15-old-russian-childrens-book.

Shin, M. (2008). The beginning of modern picure books, Russian children’s picturebooks 1920-1930. Story of Picturebooks, 4, 4-9.

Voskoboinikov, V. (2013). Children’s literature yesterday, today…and tomorrow? Russian Studies in Literature, 49(3), 62-74.

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit archival stream.

- Themes: Russia, Yoo Kyung Sung

- Descriptors: Books & Resources, Student Connections, WOW Currents

The history of picture book in Russia… I didn’t know about that. That’s very interesting to me. Creating a new nation using picture books in Russia remind me of the history of kamishibai (visual storytelling) in Japan. Kamishibai was not only entertainment but also a tool for spreading political messages during World War II in Japan. Many of the kamishibai stories told during the war time were very harsh and showed “reality” of people’s lives. For example, one of the famous stories is about the death of son in the war. The story portrays how beautiful his death is because he dies for emperor.

Looking at how people used picture books and stories in the past is very interesting. Behind the stories, there was sometimes something related to political and ideological purposes. and maybe today too?