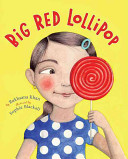

Big Red Lollipop

Written by Rukhsana Khan

Illustrated by Sophie Blackall

Viking, 2010

ISBN: 978-0670062874

Rubina runs home from school excited that she’s been invited to a birthday party. She explains to her mother, Ami, what birthday parties are since Ami is not familiar with them, while her younger sister Sana screams, “I wanna to go too!” When Ami insists that Rubina take Sana with her, Rubina has no choice. Sana’s behavior at the party embarrasses Rubina but all seems to be forgotten when the sisters receive goodie bags that include candies, toys, and a big red lollipop when they leave. Sana’s goodies are gone or lost by bedtime. Rubina places her lollipop in the refrigerator to save until morning and dreams of eating it all night long. When she goes to get it the next day, all that’s left on the stick is a little triangle. Sana! Rubina is angry and chases Sana around the house, waking up Ami who maintains that Rubina needs to share with her sister. The worst part for Rubina is that she isn’t invited to any more parties because her friends know Sana will come too. Time passes and when Sana is invited to a birthday party, their younger sister Maryam begs to go. Ami tells Sana it’s only fair that Maryam go, since Sana went to a party with Rubina. Rubina is torn as to whether or not she should intervene, but finally “takes action” and asks Ami to let Sana attend the party by herself. After the party, Sana knocks on Rubina’s door and hands her a big green lollipop.

This story is special to Rukhsana Kahn because, other than the green lollipop, it’s true. Khan was Sana (note the similarity of the name to Rukhsana) and demanded to accompany her older sister to a birthday party, much to her sister’s dismay. In personal communication, Khan explained that the context of the story is a Muslim family in Pakistani culture, living in North America. Kahn was born in Pakistan and immigrated to Canada when she was three years old. While many Pakistanis now celebrate birthdays, that was not the case years ago and some still do not. When Khan was growing up, Pakistani children would not go somewhere alone; invitations always included the family. That also has changed within some Pakistani-Muslim families in the west.

In the story the clash between sisters, cultural traditions, and a parent’s response to a child’s view of what’s “fair” are quite powerful. The humorous telling prevents this from becoming too intense, however. Tensions are resolved by the end as the sisters become friends, each with deeper understandings of themselves, each other, and what’s important.

Blackall’s illustrations are watercolor and pencil, with minimal background, drawing attention to the characters and their emotions. Red and green colors are included in the illustrations throughout the story. The pages are also rich with colorful patterns, which Blackall repeated on the endpapers.

This book would work well in a text set on how birthdays are acknowledged in different cultural traditions. Other books in that text set might include: What Will You Be, Sara Mee? (Kate Aver Avraham, 2010), Happy Birthday, Jamela! (Niki Daly, 2006), Birthdays around the World (Mary Lankford & Karen Dugan, 2002), and, for very young children, Birthdays in Many Cultures (Martha Rustad, 2008).

Prisca Martens, Towson University, Towson, Maryland, USA

WOW Review, Volume III, Issue 4 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/review/iii-4/

this is one of my favorites. great review, connected to reality very well.

This is a very unique book written about Maasai culture primarily from the perspective of a pre-adolescent female growing up in that world. A very engaging book in terms of background, cultural perspectives, and the surprising universalities of growing up, regardless of where in the world you are. The female protagonist, Namelok, will undoubtedly give new insight into what it means to be young in Africa to Western readers. This book is particularly enjoyable in terms of how it gives snapshots of what we have already seen about the Maasai culture, Kenya, wild African animals, etc. Yet at the same time, the viewpoint and perspectives of the people inside that culture take it a step further in terms of their modern struggles, survival, traditions, and what that means for the modern day Maasai. What I found particularly interesting are the explanations of how an African tribe views animals and their natural world, along with the ways in which they connect with it. Will that world be lost forever this century? It is a theme that shines through as a common thread running across the pages of this very original book written by a Westerner, Cristina Kessler, under the guidance of Kakuta Ole Maimai Hamisi, a Maasai who helped in the editing of the manuscript. This book stands out as another fine example of African literature, which is a literature that we know little of in North America, and that we undoubtedly need to get much closer to.

For your in formation “wunschkind child without a country” by Liesel Appel as paired in your review of “Traitor” was written by Mrs. Appel where she adapted her memoir “The Neighbor’s Son”for young adult readers. The site is wwwtheneighborsson.com.