by Charlene Klassen Endrizzi, Westminster College, PA, Bobbi Jentes Mason, Fresno Pacific University, CA, Karen Matis, Shenango Area School District, PA and Grace Klassen, Exeter School District, CA

“It is hard to argue that housing is not a fundamental human need. Decent, affordable housing should be a basic right for everybody in this country. The reason is simple: without stable shelter, everything else falls apart.” (Matthew Desmond, 2017).

This month we explore an all too familiar struggle for affordable housing within some of our students’ and families’ lives. Last week we offered a comfortable view of home ownership for two distinct families. This week we move into uncomfortable, unreliable spaces as families struggle to find a path forward.

Home is contextual. Each individual defines a home based on circumstances that include structure and family. Exploring positive environments and families as well as difficult situations help children begin to understand the complexity in defining “home.” Adolescents bring unique challenges to consider as they grapple with their own developing bodies, and young adult authors capture the nuances of adolescent development as it relates to the definition of home.

Imagine being in the footsteps of 13-year old Genesis, the protagonist in Alicia D. Williams’ young adult novel Genesis Begins Again, who has lived through multiple evictions from her home. Furniture and personal belongings strewn across the common space of the apartment complex, Genesis internalizes her family’s misfortunes, blaming herself for her father’s gambling and drinking problems. Genesis did not inherit her mother’s light skin tones; she favors her father’s dark features and endures his verbal abuse related to her skin tone trait. The uncertainty of where she is going next is vivid in her thoughts, “We say goodbye to Euclid Avenue, and hello to – where are we going to now?” In her novel, Williams outlines Genesis’ list of 96 reasons this teen dislikes herself. Genesis’ definition of home might include words like broken, uncertain, and unreliable; she might use these same adjectives to define herself.

Enter an educator who finds value in all her students. Mrs. Hill, Genesis’ music teacher, artfully introduces her to the biographies of Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald. Through Holiday’s early years of extreme poverty, dropping out of school, and working in prostitution to support herself, Genesis begins to find her own voice. That voice becomes even stronger after learning about Fitzgerald’s early struggles as a school dropout, working for the mafia, and running away from a girls’ reform institution. Through Mrs. Hill’s subtle mentoring, Genesis begins to understand how she can alter her definition of home as well as how she views herself. She might not get a big break like these two famous performers, but the power and agency to alter her perceptions are purely her own.

Parked is Danielle Svetcov’s story of seventh grader Jeanne Anne and her hopes for a better future. With her mother at the wheel, they drive their home, a beat-up orange van, traveling from Chicago to San Francisco. Jeanne Anne’s mother parks the orange van, now with a flat tire, on a side street as they join others who have also taken up residency in their vehicles. Amidst million-dollar homes with manicured lawns offering a breathtaking view of the Golden Gate Bridge, conflict is swift as occupants of the beautiful properties seek to actively remove these “vehicular vagrants.” Two lifestyles present stark contrasts, and though it may appear that lines have been drawn, Svetcov creates friendships outside of those boundaries which blur the lines of social class and complicate the meaning of “home.” Fully aware of her predicament, Jeanne Ann contemplates her situation thinking, “If you have your eyes open, you don’t get to choose what you see.”

Parked is Danielle Svetcov’s story of seventh grader Jeanne Anne and her hopes for a better future. With her mother at the wheel, they drive their home, a beat-up orange van, traveling from Chicago to San Francisco. Jeanne Anne’s mother parks the orange van, now with a flat tire, on a side street as they join others who have also taken up residency in their vehicles. Amidst million-dollar homes with manicured lawns offering a breathtaking view of the Golden Gate Bridge, conflict is swift as occupants of the beautiful properties seek to actively remove these “vehicular vagrants.” Two lifestyles present stark contrasts, and though it may appear that lines have been drawn, Svetcov creates friendships outside of those boundaries which blur the lines of social class and complicate the meaning of “home.” Fully aware of her predicament, Jeanne Ann contemplates her situation thinking, “If you have your eyes open, you don’t get to choose what you see.”

What can society do to help individuals in similar situations overcome and thrive, thereby avoiding perpetuation of these lifestyles? The answers are NOT in these young adult novels.

One initial step forward involves acknowledging the dire redlining federal laws many people of color faced in the 1930s through 1960s. Richard Rothstein helps teachers examine a complicated historical lens in his groundbreaking book The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (2018). He carefully outlines how federal mandates supported home ownership for whites while redlining policies administered against African Americans and other people of color made purchasing a home precarious, if not impossible. Sanctioned, segregated neighborhoods made it difficult for many African Americans to create generational wealth through home ownership. The legacy of these unjust policies continues to contribute to society’s inequities today. By investigating the historical uncertainty of home ownership for some, teachers can help students carefully examine this injustice for themselves.

One initial step forward involves acknowledging the dire redlining federal laws many people of color faced in the 1930s through 1960s. Richard Rothstein helps teachers examine a complicated historical lens in his groundbreaking book The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (2018). He carefully outlines how federal mandates supported home ownership for whites while redlining policies administered against African Americans and other people of color made purchasing a home precarious, if not impossible. Sanctioned, segregated neighborhoods made it difficult for many African Americans to create generational wealth through home ownership. The legacy of these unjust policies continues to contribute to society’s inequities today. By investigating the historical uncertainty of home ownership for some, teachers can help students carefully examine this injustice for themselves.

Our last two picturebooks invite readers to explore other nuanced definitions of home. “When you listen to others, you show respect; you learn who they are and what they need.” Christine McDonnell shares this insight in the picturebook Sanctuary: Kip Tiernan and Rosie’s Place, the Nation’s First Shelter for Women. An orphan before she was a teen, Kip was raised by her grandmother during the Great Depression. She witnessed her grandmother’s kindness and generosity towards men less fortunate by providing food for the hungry. Kip’s watchful eyes noticed women, who dressed like men, queued up in order to gain access to bread and soup. The common belief was that homelessness was gender specific, not affecting women. But Kip’s observations told her a different story. Women were seen sleeping on park benches and sorting through garbage for something to eat. Hard times do not discriminate; there are no color or gender boundaries.

Our last two picturebooks invite readers to explore other nuanced definitions of home. “When you listen to others, you show respect; you learn who they are and what they need.” Christine McDonnell shares this insight in the picturebook Sanctuary: Kip Tiernan and Rosie’s Place, the Nation’s First Shelter for Women. An orphan before she was a teen, Kip was raised by her grandmother during the Great Depression. She witnessed her grandmother’s kindness and generosity towards men less fortunate by providing food for the hungry. Kip’s watchful eyes noticed women, who dressed like men, queued up in order to gain access to bread and soup. The common belief was that homelessness was gender specific, not affecting women. But Kip’s observations told her a different story. Women were seen sleeping on park benches and sorting through garbage for something to eat. Hard times do not discriminate; there are no color or gender boundaries.

In 1974, Kip’s desire to follow in her grandmother’s footsteps led her to petition the city of Boston for a women’s shelter which evolved into Rosie’s Place. Her persistence paid off when the city of Boston rented her an abandoned supermarket for $1 a month. Simply put, this safe house would provide homeless women with shelter, clothing, hot meals, and friendship. With volunteers and fundraising, Kip promoted the shelter as a non-judgmental safe house for women which continues to operate today.

The illustrations in this children’s book tell yet another story. Initially in darker muted tones, as the story of Kip’s accomplishments are unveiled, the colors become more brilliant, mimicking the success of helping others. Kip’s biography is a testimony to how one person can make a positive impact and provide a temporary “home” if needed.

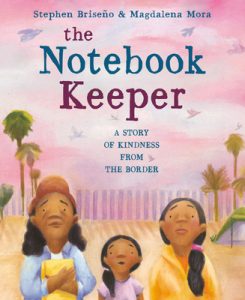

Our last narrative, a recent Pura Belpre Children’s Author Honor Book, The Notebook Keeper: A Story of Kindness from the Border, by Stephen Briseno and Magdalena More, provides readers with an asylum-seeker’s lens focused on a yearning for stability. Home evokes both hope-filled and hopeless emotions. Brisneo’s story allows us to journey north alongside Noemi and her mother, from Michoacin, Mexico to the border wall where they are abruptly halted. The author chooses not to focus on the arduous journey but instead emphasizes the endless, exhausting waiting period upon their arrival at the wall. Certainly, there is no welcoming party at the border. Noemi admits, “It’s hard to see any kindness here.”

Our last narrative, a recent Pura Belpre Children’s Author Honor Book, The Notebook Keeper: A Story of Kindness from the Border, by Stephen Briseno and Magdalena More, provides readers with an asylum-seeker’s lens focused on a yearning for stability. Home evokes both hope-filled and hopeless emotions. Brisneo’s story allows us to journey north alongside Noemi and her mother, from Michoacin, Mexico to the border wall where they are abruptly halted. The author chooses not to focus on the arduous journey but instead emphasizes the endless, exhausting waiting period upon their arrival at the wall. Certainly, there is no welcoming party at the border. Noemi admits, “It’s hard to see any kindness here.”

Yet they meet one hopeful volunteer, the notebook keeper, who maintains an unofficial numbered list of those waiting to cross over and face Immigration and Naturalization officers. Waiting in hopes of finding a new home builds connections amongst refugees. Worry and uncertainty could readily consume Noemi and her mother, Manuela. Somehow this young child’s keen awareness enables her to ponder, “I wonder how Belinda (a.k.a. the notebook keeper) can keep her smile. I feel mine fading each day.” At the crossroads of hope and despair, Noemi finds the courage to emit hope for herself and those around her. When Belinda hears her number called, the mother/daughter duo are chosen to take up the mantle of notebook keeper, ones who offer encouragement and comfort to those in the waiting phase.

And so, we circle back to our essential questions that launched this exploration of home earlier this month. When you consider students you learn with, how do you imagine they perceive home? Certainty or uncertainty? Additionally, what makes a home? Is it a place? Is it people? or a feeling? What makes a house a home?

We believe a path forward toward more “light-filled rooms for all” (Danielle Allen, 2023) means raising our awareness about decent, affordable housing for every family. It involves deepening our historical and contemporary awareness of the struggles some people have faced and still face, in apartment complexes which Genesis longed to escape, in orange vans like Jeanne Ann’s, in shelters organized by Kip Tiernan and at borders with generous notebook keepers. We look to justice-minded citizens and legislators as well as teachers who can begin to open eyes by initiating critical conversations about the human need and basic right to find more light-filled rooms for all.

WOW Currents is a space to talk about forward-thinking trends in global children’s and adolescent literature and how we use that literature with students. “Currents” is a play on words for trends and timeliness and the way we talk about social media. We encourage you to participate by leaving comments and sharing this post with your peers. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit its archival stream.

- Themes: Alicia D. Williams, Bobbi Jentes Mason, Charlene Klassen Endrizzi, Color of Law, Danielle Svetcov, Genesis Begins Again, Grace Klassen, Karen Matis, Magdalena More, Notebook Keeper, Parked, Richard Rothstein, Sanctuary: Kip Tiernan and Rosie's Place the Nation's First Shelter for Women, Stephen Briseno

- Descriptors: Books & Resources, WOW Currents