Get to know Japanese Manga Up Close and Personal: Children and Youth Choices for Fun

This past spring, Junko visited a 6th grade classroom in Tucson, Arizona. She watched three girls having fun reading together. These readers kept reading and shared their thoughts from their reading any time and anywhere they could, like in the classroom or at recess. Holding their attention--Japanese comic books called manga. It didn't take long for those manga fans to ask Junko any number of questions about Japan. Their knowledge was based on the popular Japanese manga they had read, so it was thoughtful. The 6th-grade manga fans were not shy about showing off that they read manga alongside other novels. The fact that they read manga whenever possible makes them similar to "book nerds," except people wouldn't call manga fans "nerds" because manga is meant for pleasure and fun. It is not traditionally considered as literature with a high literary value.

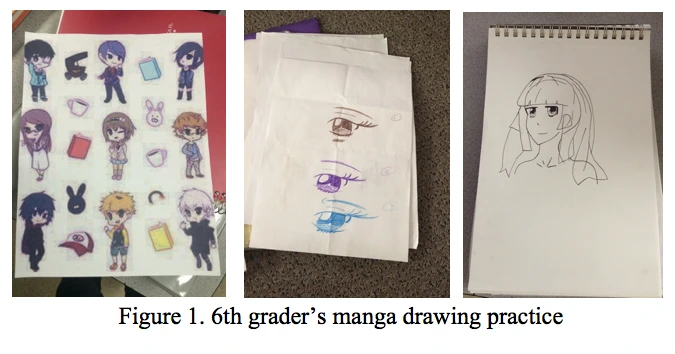

These manga fans were more proactive about reading manga than any other reading material. They also took powerful ownership of manga reading in their spaces, reading blocks and recesses. They even invited grown-ups like Junko to join their conversations. Not only that, they chatted about stories and characters as if having traditional book discussions. Soon they asked Junko questions about Japanese language and illustrating techniques in manga. They not only read manga but also imagined themselves being manga illustrators. They practiced different styles of emotive manga arts in their drawings (see Figure 1). Working on styles of characters is fun. The 6th graders studied major visual elements such as lines, colors, textures, etc. After all, going to Japan to become a manga artist is not just a dream of 6th graders, but manga fans from around the world work towards this dream.

Manga appears to be a powerful tool that can forge international connections between Japanese adults and American children like Junko and the 6th graders. Even though manga has earned popularity among young readers, manga hasn't earned much credibility as valuable reading material. In recent years, we have seen young students reading manga in classrooms and school libraries in Tucson, and local bookstores have busy manga corners full of teenage fans.

Manga (マンガ) is a Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese character, 漫画, which is pronounced "manhwa" (만화) in Korean. Whether it is called manga or manhwa, the nature is similar. The similarity in these sequential art texts is a global experience that we, Yoo Kyung and Junko, share as a cultural consensus in our childhood and manga reading. Because of intensive school schedules and test-oriented school cultures in Korea and Japan, manga/manhwa is one of the few gateways for pleasurable reading options for children, tweens and high schoolers. The nature of "texts light" is easy to read, and the beautiful artwork leads the story with great drama (Gibson, 2009). In the 1980s, private manga/manhwa rooms or private manga libraries, where we paid five cents or less per volume, were popular. Completing a story of twenty to fifty volumes was not expensive. Young customers sat and read as many as they wanted or could afford in terms of time and money.

The 6th graders in Tucson might experience something similar to the beautiful storytelling in Japanese manga that doesn't end a story in one volume. Twenty to fifty or so volumes are necessary to continue a story and achieve its completion. Manga/manhwa is one of the most significant childhood and youth cultures in Japan and Korea. These sequential art texts are a type of cross-over picturebook, in the broad definition, because it often continues to adulthood in terms of pleasurable reading. We see this manga reading habit occurring among the youth in the U.S. Monnin (2016) notes, "According to Reading Engagement Theory, which states that 'schema, choice, motivation, and interest increase comprehension,' graphic novel adaptations of canonical texts best exemplify what type of text today's readers of all abilities not only desire to read but also best comprehend" (p. 39).

This month, we talk about manga/manhwa as a part of childhood and youth culture, which forms a membership and fandom around manga artists and characters, accompanying cultures in texts. Next week we start with a brief history of Japanese manga and introduce the complexity of manga categories, which are practiced differently in the U.S. from Japan and Korea. We hope teachers do not feel reluctant to exhibit manga/manhwa in their classroom spaces despite the lack of information in "canonical texts"(Monnin, 2016). We also share 6th graders' choices of manga and their responses to their favorites along with an introduction to manga creators. In the final week, we share text sets including manga/manhwa and children's literature to be used as culturally diverse text sets. These text sets integrate manga as a range of types of books, so that it doesn't remain classified as "light books" that only students are eager to read. After all, "working" reading means books we cannot keep students from reading.

Manga needs to be reconsidered because of the importance of the aesthetic responses that have arisen from efferent responses to Japanese styles of comic books. We refer to entire canonical texts as manga in this blog series since manga is a more well-known expression than manhwa, and our focus will stay on Japanese manga.

Reference

Monnin, K. (2016). Manga brings new life to classic literature. Publishers Weekly, 263(34), 39.

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. Check out our two online journals, WOW Review and WOW Stories, and keep up with WOW’s news and events.