Celeste Trimble, St. Martin’s University, Lacey, WA

In Lakota language, water is called mni wiconi, literally “it gives me life.” Without water, there would be no life. Water is fundamental for every living being on this planet. Indeed, water, too, is living. Indigenous communities around the globe have always known that protecting and repairing water is essential for our survival. Stories of the the importance of water, its sacredness, and the fight of the water protectors are present in literature for children and young adults.

This month, Autumn Peltier, a fifteen year old from Wiikwemkoong First Nation in Canada, spoke at the United Nations General Assembly. Her message was clear: we must take action to protect the waterways and bodies of water on our planet. It isn’t enough just to know that water is life, we must act, and she is modeling this for everyone. Her great aunt, Josephine Mandamin, was known as The Water Walker, as she walked around the entire perimeter of the Great Lakes in an effort to bring awareness to the importance of protecting the water. Autumn wanted to continue the legacy of her great aunt who passed away this last February.

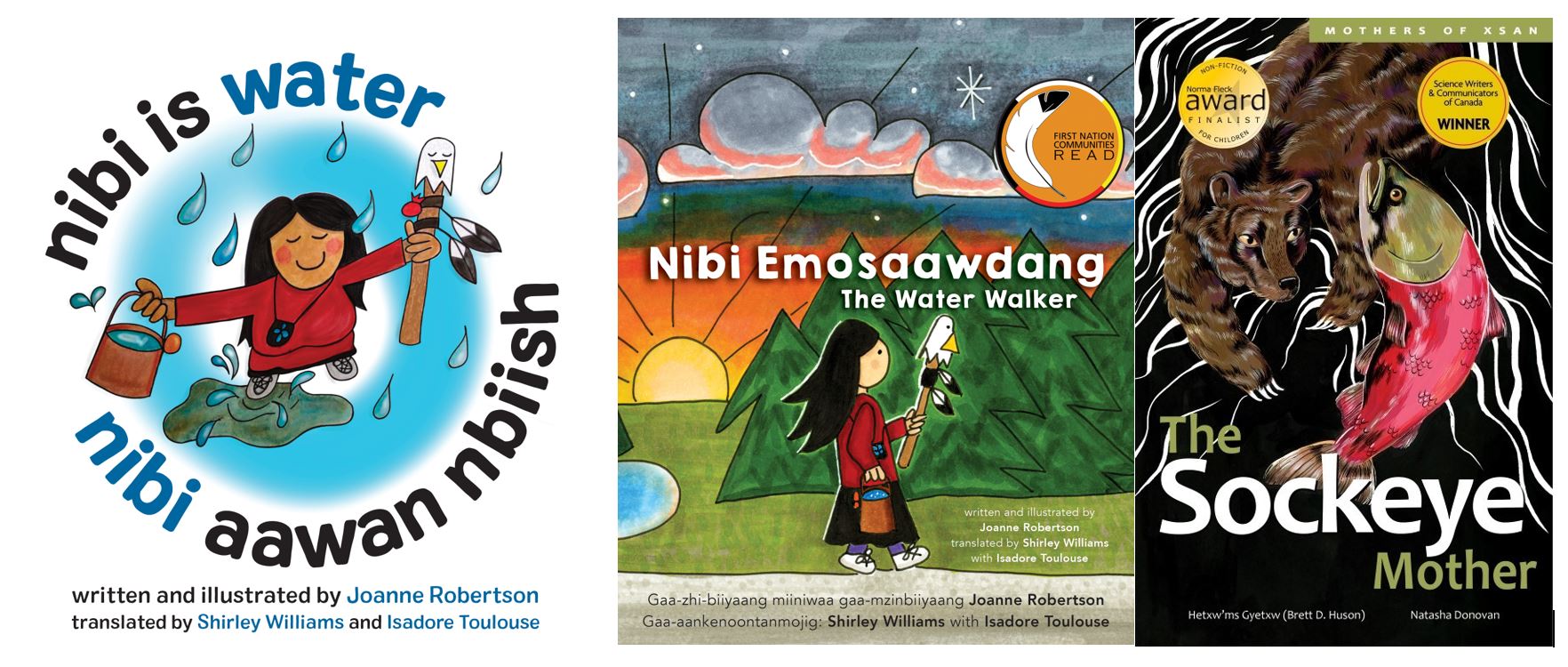

Indigenous author and illustrator Joanne Robertson, inspired by meeting Josephine Mandamin, created a picturebook to bring the story of The Water Walker to inspire children. It was selected as a First Nations Community Reads. Indeed, it has inspired children to work to raise awareness about and protect the waters. A group of fifth and sixth graders in Canada are now calling themselves Junior Water Protectors, and working to inspire other kids to take up the same activism. Joanne Robertson’s forthcoming book, Nibi is Water, will be published in 2020.

Another young writer has been inspired by the need to fight for Indigenous water rights. Ten year old Aslan Tudor, a citizen of the Lipan Apache tribe of Texas, wrote a book with his mother, Kelly Tudor, to tell the story of his experience as a water protector at the Oceti Sakowin Camp on Standing Rock Sioux land. Young Water Protectors: A Story about Standing Rock was published this month, illustrated with photographs from Standing Rock. It is wonderful to read the background information about the struggle to fight against the Dakota Access Pipeline and to protect the sacred waters from a child’s perspective. In addition, Tudor writes about what it was like to be a child participant in this struggle, including discussing attending the children’s Defenders of the Water School at the camp.

Just like The Water Walker inspired students to become Junior Water Walkers, and the experience at Standing Rock inspired Tudor to become a writer and share his experience, seeing Indigenous authors on the bookshelf inspires more Indigenous people to become writers. When Sunshine Tenasco saw a book by Monique Gray Smith with an Indigenous girl on the cover, she decided that she, too, could be an author (I’m not sure which book, but I imagine it is My Heart Fills with Happiness). Tenasco is from Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg, Quebec, Canada, which has been without clean drinking water for 15 years. She founded a company, Her Braids, that has dedicated 10% of profits to the Blue Dot environmental movement, which works for access to clean water in all communities across Canada. Now, she is also the author of Nibi’s Water Song, illustrated by Chief Lady Bird. In this book, Nibi is thirsty but cannot find any drinking water. She hopes that the book will help inspire other young people to fight for change in positive ways.

Not all books that are advocating for protecting waterways are explicitly about the water itself. The Sockeye Mother by Hetxw’ms Gyetxw (Brett David Hudson) and Natasha Donovan describes how the water, the animals, the soil, and the cycles of the year are intertwined. Without clean, healthy water, the salmon can not exist and survive. This book describes how the salmon nourish not only the people’s bodies, but also their culture and ceremony. “Little does this small sockeye fry know that its life cycle not only nourishes the people and other beings along the watersheds, it is the whole reason the forests and landscapes exist.” This book includes words in Gitxanimaax language with an online pronunciation guide. It also includes a map of the waterways important in the Gitxan Nation in the unceded territories of British Columbia.

I wondered, while reading and thinking about these North American Indigenous children’s books regarding water, about Indigenous peoples around the world and their relationships with water. In 2017, the marvelous Tara Books published Water by Subhash Vyam with Gita Wolf. Many of the illustrators at Tara Books are a part of India’s Adivasi Indigenous community. Vyam is a Gond artist working in the traditional Gond visual style. Water intertwines contemporary water issues in India in both small villages and cities together with a traditional Gond fable about water and the dangers of what can happen when we abuse natural resources.

Finally,We Are Water Protectors, by Carol Lindstrom (Turtle Mountain Ojibwe), with illustrations by Michaela Goade (Tlingit, Haida) will be available in March of 2020. This book offers strength for this fight to protect the waters and the natural world with optimism and hope. Through the references to the struggle at Standing Rock and the Ojibwe prophecy about a black snake, We Are Water Protectors grounds intentional optimism within the work that we all have to do for all of us to survive. Lindstrom unites readers with her poetic and gentle words, while Goade’s incredibly beautiful illustrations help readers realize that it is a beautiful and necessary thing to fight for our water, our world, together. In one image, a young girl, with the words “Water is the first medicine” in her thoughts, is taking courage and leading the fight, reminding us that youth are the leaders, and that all of us must pay attention. I can’t wait to read and discuss this book with young people.

Mni wiconi.

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit archival stream.

- Themes: Aslan Tudor, Brett David Hudson, Carol Lindstrom, Celeste Trimble, Chief Lady Bird, Gita Wolf, Hetxw'ms Gyetxw, Indigenous, Joanne Robertson, Kelly Tudor, Monique Gray Smith, Natasha Donovan, Nibi is Water, Nibi's Water Song, Sockeye Mother, Subhash Vyam, Sunshine Tenasco, Water Walker, We Are Water Protectors

- Descriptors: Books & Resources, WOW Currents