by Daliswa Kumalo and Charlene Klassen Endrizzi

Two years ago, Daliswa “Didi” Kumalo shared a compelling picturebook, Let the Children March, with third graders during our School of Education’s annual African American Read-In. She recently revealed the impetus for crafting this engagement. “When I was younger, my dad always told me that ‘history tends to repeat itself.’ As much as I wished that wasn’t the case, as I get older the connections to the past have never felt closer.” Through our blog post, I (Charlene) reveal Didi’s ability to connect 8- and 9-year-olds to the Civil Rights child foot soldiers featured in Monica Clark-Robinson and Frank Morrison‘s award winning book. We believe this literature engagement highlights the value of building bridges to our nation’s past. When teachers initiate hard conversations surrounding unresolved racial struggles, children can begin to consider their power to create much-needed change today.

Two years ago, Daliswa “Didi” Kumalo shared a compelling picturebook, Let the Children March, with third graders during our School of Education’s annual African American Read-In. She recently revealed the impetus for crafting this engagement. “When I was younger, my dad always told me that ‘history tends to repeat itself.’ As much as I wished that wasn’t the case, as I get older the connections to the past have never felt closer.” Through our blog post, I (Charlene) reveal Didi’s ability to connect 8- and 9-year-olds to the Civil Rights child foot soldiers featured in Monica Clark-Robinson and Frank Morrison‘s award winning book. We believe this literature engagement highlights the value of building bridges to our nation’s past. When teachers initiate hard conversations surrounding unresolved racial struggles, children can begin to consider their power to create much-needed change today.

This month, we use our first WOW Currents post to outline the text’s historical moment set in the Civil Rights era. Highlights of Didi’s read aloud are followed by examples of third graders’ letters mailed to brave child foot soldiers she located in Birmingham, Alabama. Our second post features letters of response sent by actual civil rights marchers. Along the way, we highlight digital resources Didi discovered to emphasize the importance of visual literacy for inspiring greater compassion.

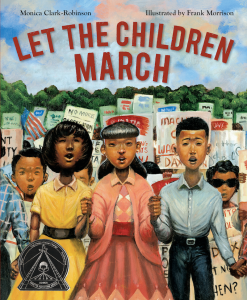

While developing a read aloud, we encourage teachers to make time to first expand their own perspective. As a student of color, Didi set out to deepen her awareness of her own history. Let the Children March brings together Monica Clark-Robinson and Frank Morrison, who depict a tumultuous 3-day struggle that helped launch the Civil Rights Movement. Almost 60 years ago, child foot soldiers voluntarily marched in the streets of Birmingham during The Children’s Crusade in response to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s call for support. Several thousand young Black protestors risked their safety to spotlight racial inequality. Their distressed parents, fearing police brutality and job loss, observed from the sidelines. The author chooses a young girl as the voice of many brave marchers who were attacked by dogs, hosed and arrested. Morrison’s oil paintings strikingly capture the intense faces of young protestors who never lose their dignity while encountering angry counter-protestors and a hostile police force. The central role of children as change agents is a driving force throughout this text.

In her closing pages, Clark-Robinson explores the optimism child foot soldiers and their families must have felt when white Birmingham city leaders reached a tentative agreement with Dr. King. Yet a repetitive banner seen on several book pages reminds readers that the road ahead towards desegregation is “LONG AND TROUBLED.” Morrison’s depiction of the Confederate flag on the second to last page reminds us of our nation’s present-day racial tensions. We encourage teachers to not miss the thought-provoking timeline of key events in 1963 through 1965, presented on the opening and closing end-papers. Didi’s discovery of the Learning for Justice DVD kit – Mighty Times: The Children’s March – helped her uncover details for her google slideshow which added depth to her read aloud experience.

Children’s Crusade Foot Soldiers 1963

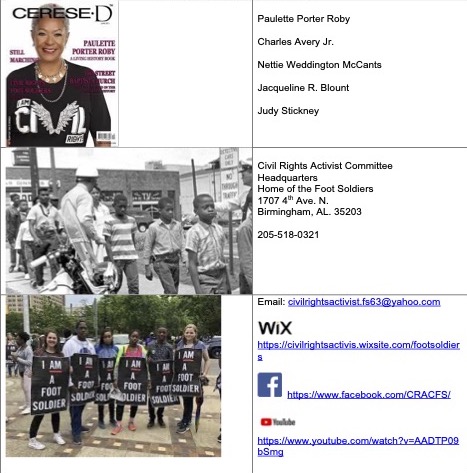

Paulette Roby, Chairwoman Civil Rights Activist Committee

Our annual one-day African America Read-In celebration held at an elementary school within a predominantly Black community required Didi to plan her limited time frame carefully. Days of online searching led her to the Civil Rights Activist Committee headquarters in Birmingham. Paulette Roby, current chairwoman of the committee, graciously agreed to share home addresses of child foot soldiers (with permission). These 60- and 70-year-olds remain active in their work with children and adolescents.

The morning of our school-wide Read-In, Didi arrived in her third grade classroom with multiple resources. Questions crafted ahead of time asked students to dive into this historical moment. For example, Didi invited students to offer personal reactions, wonder about their own family member’s potential reactions and consider the author’s goals. Her Google slideshow of newspaper clippings and photographs from May 2-4, 1963 offer an essential visual text to compare with Morrison’s illustrations. Monica Clark-Robinson’s webpage, the Civil Rights Activist Committee’s Facebook page and Wix website (linked in previous paragraphs) were useful references to use during her literacy engagement. A second Google slideshow provided letter writing tips along with child foot soldiers’ home addresses.

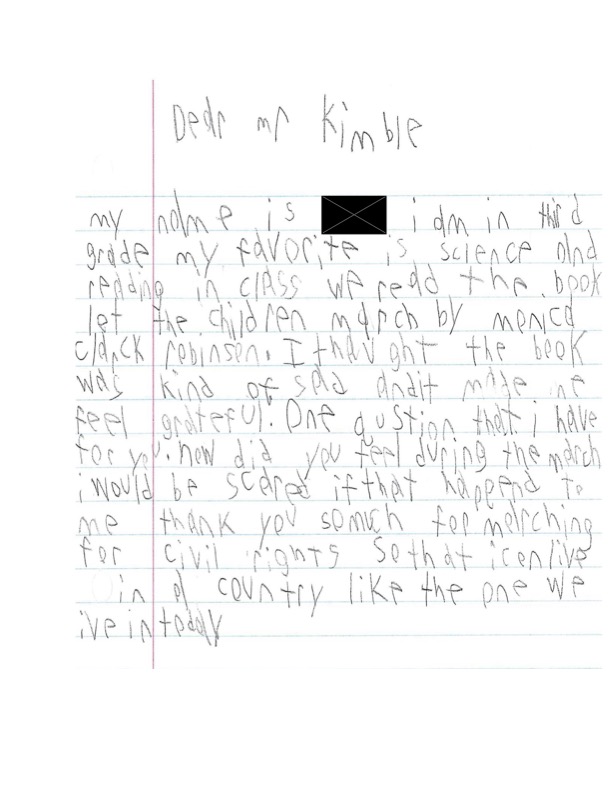

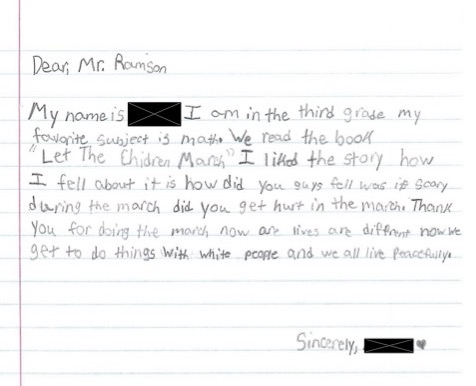

Ideally we hoped for more classroom time to delve further into students’ reactions and questions. Nonetheless Didi’s endeavors with 17 third-graders over 90 minutes are instructive. Two of her third graders’ letters shown here outline their evolving understanding of this tense encounter between white policemen and black children. Many students used their letters to express gratitude through comments like, “Thank you so much for marching for civil rights.” They pose practical questions such as, “How did you know which way to go?” Third graders focused on safety concerns, seen in questions like, “Were you scared when you went to jail?” Some of them close by reassuring foot soldiers about their decision to march with comments like, “That was the right thing to do.” Several last statements such as, “Our world is a better place today,” give us a good deal to ponder for next steps.

Currently Didi is a new fourth grader teacher in Fairfax, Virginia. She recently shared this look back and revealed her continuous efforts to create a safe space for complex discussions. “Having difficult conversations with students is important because it helps them know that we acknowledge their fears and concerns and lets them know that their contributions are valid. Children should be able to ask questions and make connections to what they see, with a safe adult to help facilitate their thinking. I want students to be critical thinkers and look at the world through a lens of compassion. Having authentic, real conversations with them is the first step towards breaking the cycle of repetition.”

Didi’s anti-racist teaching lens urges us to keep creating contexts for difficult conversations with students. Broadening literature explorations to include trailblazers from our past can help build bridges for essential personal connections that inspire further action.

In the forthcoming Marching for Justice for All: Part 2 post, we explore treasured letters from seven Birmingham child foot soldiers and third graders’ reactions. We invite you as readers to pose your initial questions and reactions in the comments.

WOW Currents is a space to talk about forward-thinking trends in global children’s and adolescent literature and how we use that literature with students. “Currents” is a play on words for trends and timeliness and the way we talk about social media. We encourage you to participate by leaving comments and sharing this post with your peers. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit its archival stream.

I believe that now, more than ever, lessons like Didi’s are needed to help young learners understand and navigate the complexities of unresolved racial struggles. In addition to learning about the child foot soldiers, her students were challenged to compose letters to these brave individuals. Real life learning experiences help children begin to see beyond physical traits and take a deeper look at individual behaviors, attitudes, and actions. When our young learners adopt a mindset that “The world is a better place today,” hopefully they will strive to continue promoting and living that very ideal being activists for equality for all.

As a secondary education student teacher, I completely agree with Didi’s that “authentic, real conversations” are essential to breaking cycles of racism and anti-Semitism. These conversations are very difficult for students of all ages, backgrounds, and races but they must be discussed in safe environments. Thank you for your post!