by Daliswa Kumalo and Charlene Klassen Endrizzi

This week Daliswa (Didi) and I continue our look back at her African American Read-In experience with third graders, inspired by their exploration of Let the Children March. We share letters sent to students from foot soldiers still residing in Birmingham, Alabama and then consider third graders’ reactions. This insight from Desiree Cueto sums up our overarching intentions. “Our hope is that this work will inspire others to be courageous in their teaching and in their resolve to usher in a new generation of thoughtful and compassionate citizens.”

Like historians, teachers often spent time hunting for primary sources, to bring history to life. And when an eight or nine-year-old receives a primary source document like a letter, it becomes an inspirational moment. Third graders were thrilled to receive seven personalized notes from foot soldiers. As letters arrived over a three-week span, the classroom teacher read each one aloud, passed them around for further inspection and established their value as communal property.

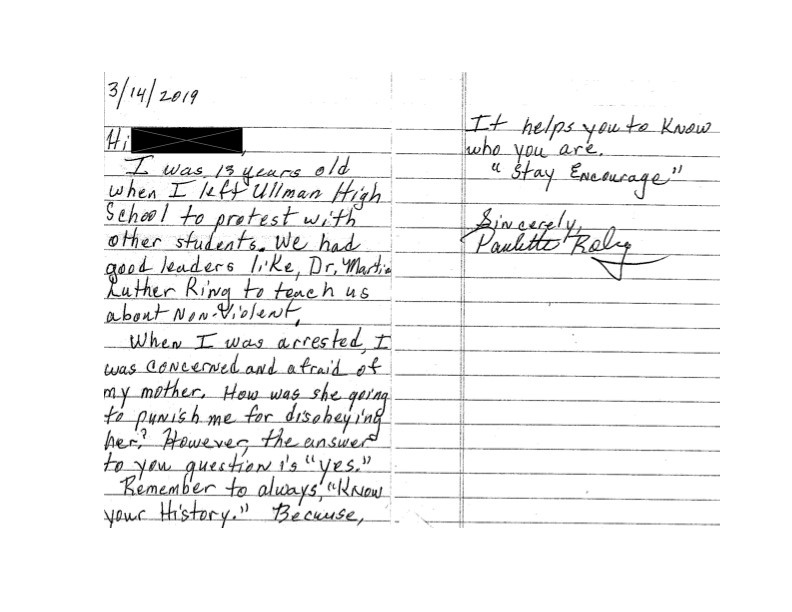

Let’s examine the first of two letters Paulette Roby sent to different third graders. Ms. Roby links historical facts portrayed in the book to her childhood. Revealing her age at the time of her unjust arrest, naming her high school and reminding students of her connection to a powerful teacher, Dr. King, verify her role in history. Describing her worry over her mother’s possible reaction to her arrest and disobedience makes this march become even more real. Ms. Roby’s openness brought specificity to Didi’s read aloud, making history spring to life.

Both Didi and I honed in on Paulette’s familiar, almost urgent reminder in her conclusion. The candor in her statement, “Know your History,” struck a familiar chord to Didi’s dad’s counsel, “History tends to repeat itself.” Ms. Roby from Alabama and Didi’s father, an immigrant from South Africa, both grew up during turbulent civil rights movements. Their cautionary reminders to children speak of lessons yet to be learned. Currently Paulette continues to share her complex memories with school children at the Civil Rights Activist Committee/Foot Soldiers headquarters in Birmingham.

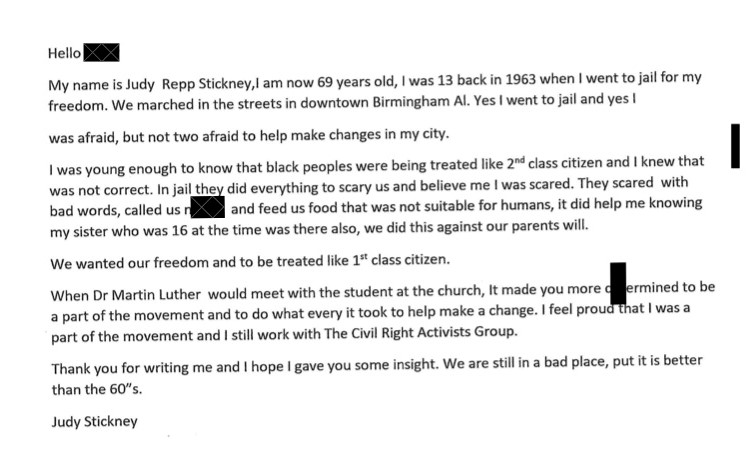

Another letter from a second foot soldier, Judy Stickney, situates her memories in a different way. Like Paulette, she conveys her young age at the time of her arrest, Dr. King’s central role and her parents’ initial disapproval. Details regarding the unsuitable food dispensed in jail and racial slurs hurled by police add depth and context to this tense era. Ms. Stickney’s rationale for her participation and desire for change comes through clearly in this comment, “We wanted our freedom and to be treated like 1st class citizens.” Her closing thought, “We are still in a bad place, but it is better than the 1960s,” connects this turbulent time to our nation’s present-day struggle focused on seeking justice for all marginalized people.

Several weeks after our African American Read-In, Didi was invited back for a second conversation with third graders. The seven thought-provoking letters from foot soldiers helped us craft an opportunity for students to mull over historical facts for themselves. Didi revealed her mindset for her next discussion in this way. “Like any unjust and uncomfortable situation in history, presenting it to children is challenging, yet crucial.” Herein, she acknowledges the tension along with her determination for exploring hard social justice issues with students.

To set the stage, Didi began this conversation by sharing a short video clip of Mighty Times: The Children’s March to renew students’ focus. Then partners re-read each of the foot soldiers’ letters, using highlighter pens to note their discoveries. Didi concluded by giving students time to draw and record their feelings and interpretations. Through each step, she focused on developing reflective conversations to build deeper connections.

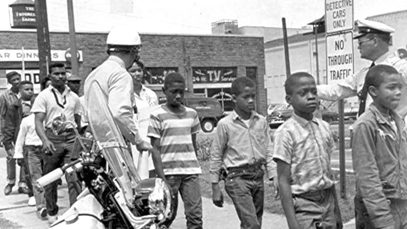

We offer four illustrations to help us consider these third graders’ depth of understanding. Both Didi and I quickly noted students’ focus on signage and speech bubbles. The third grader’s illustration seen at the top conveys a loud message, “No,” depicted in his second story frame. For us, this signals the inner resolve portrayed by foot soldiers as they withstood water hose attacks, seen in the third story frame. Another student’s drawing depicts notices such as “White Only,” portraying a desire to be treated equally, also conveyed in Ms. Stickney’s letter. Several speech bubbles such as “We should be treated right” seem to acknowledge the frustration but also hope several foot soldiers expressed through their letters. Third graders appear to be pondering the potential within non-violent marches to bring about greater compassion in our world.

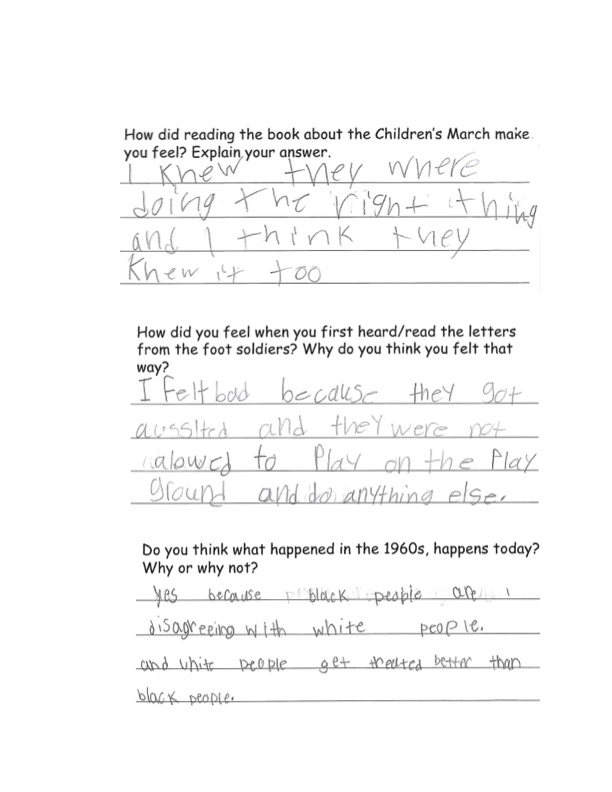

We continue analyzing students’ insights through their written responses to questions Didi posed. We believe the first student’s comments, seen at the top, express her agreement with the foot soldiers’ desire for equal justice – “I knew they were doing the right thing.” Another child’s response suggests compassion for other kids – “I felt bad because they got assaulted…” We note the third student’s comment addressing present-day racial inequality since only one other student offered a similar insight, aligned with Ms. Stickney’s assessment – “We are still in a bad place…”

Collectively these students lay the groundwork for next, valuable conversations. The challenge of establishing spaces for hard conversations is an essential, long-term goal in any classroom. In hindsight, Didi described her second discussion with third graders this way. “Together we pushed the uncomfortable boundary of racism and engaged in meaningful and thoughtful discussion.” Additionally, we acknowledge the need for further work.

I recently asked Didi to clarify her goals for book explorations with her diverse class of fourth graders this school year. “Having school-wide cultural celebrations like the African American Read-In provide students [of color] with an opportunity to see themselves, their communities, and their loved ones represented. It is our job as educators to create a space where all students feel like they belong. Having events that highlight marginalized communities gives us the ability to help students grasp the concept of diversity and make connections to the world around them. It is also gives us an opportunity to learn from them and reflect on our implicit biases.”

In closing I marvel at Didi’s ability to see the potential in connecting children with civil rights activists. Didi along with third graders and foot soldiers like Ms. Roby and Ms. Stickney encourage us as teachers to analyze our cultural biases while exploring historical stories of hope. Paulette Roby’s last words of advice – “Stay encouraged,” nudge children and teachers to keep going. And so we invite you to find opportunities for lessons yet to be learned in your march toward greater justice and compassion.

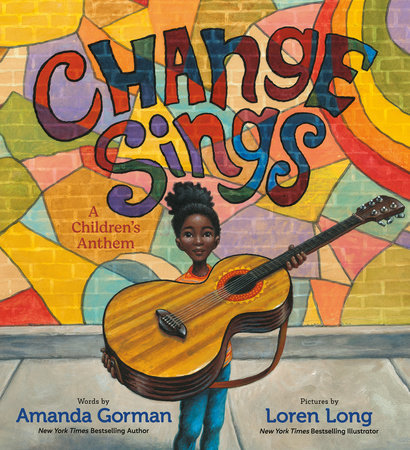

Please visit Deanna Day-Wiff’s recent post A Dozen Books on Activism to find additional books focused on helping children become more compassionate citizens. One of texts featured, Change Sings, poignantly urges students and teachers to seize opportunities for showing empathy.

WOW Currents is a space to talk about forward-thinking trends in global children’s and adolescent literature and how we use that literature with students. “Currents” is a play on words for trends and timeliness and the way we talk about social media. We encourage you to participate by leaving comments and sharing this post with your peers. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit its archival stream.