By Rebecca Ballenger, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ

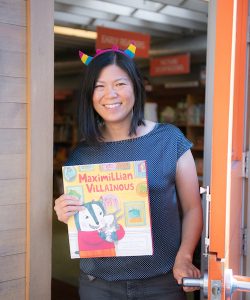

Unlikely author Margaret Chiu Greanias struggled in Language Arts and English classes throughout school but still managed to write her first book in fourth grade. And that was it for a long time. Then, during the last quarter of her last year in college, Greanias took a creative writing class that turned things around for her writing career. Today, her picturebooks include Maximillain Villanous, Amah Faraway, Hooked on Books and her newest release, How This Book Got Red. In this Authors’ Corner Greanias discusses her new book, representation in children’s literature, her writing process and school visits.Writing How This Book Got Red

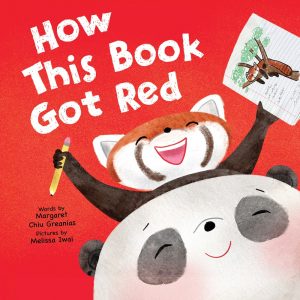

How This Book Got Red follows the story of Red, a red panda who can find books about pandas but never ones about red pandas. Accordingly, Red takes action to write her own book with the support of her friend, Gee. And that’s also how Greanias began the process of writing this book – to create a picturebook that features the “lesser” read about panda, the red panda, as a main character.

Greanias learned a great deal about red pandas from her research. She learned that red pandas are sometimes called “lesser pandas” even though they were the first animals biologically taxonomized as pandas. She also learned that, like the giant panda (the iconic black and white version), red pandas are endangered.

At the same time, she noticed a disparity in the visibility of red pandas versus giant pandas. Giant pandas are a national treasure in China whose government backed conservation efforts around giant pandas and their habitats. People in the U.S. flock to zoos to see giant pandas; this includes 10-year-old Greanias, whose class made a special stop to see giant pandas on a field trip. Most people would likely use the words “black” and “white” to describe pandas generally.

“I started to draw parallels between those of us who have been absent from books, television, movies, and other media until recently and the red panda,” says Greanias, the daughter of Taiwanese immigrants. “I realized I could use this story to explore how this absence impacted my view of myself and my culture.”

Growing up in the 1970s and ’80s, Greanias didn’t see many Asians in the books she read, the toys she played with or the food she craved. When she did see Asians, they filled stereotypical and negative roles – and were not main characters. She says being left out is not a good feeling and can negatively impact self-worth.

“The stars, main characters, and models in TV/movies, books, and magazines were ‘the cool kids.’ By our very absence and the generally stereotypical and negative portrayals, Asians were not,” Greanias says. “I don’t remember consciously thinking that I missed seeing Asians like me in the things I watched, read, or even played with. But I internalized the negative effects of it just the same.”

This absence gave Greanias the feeling that Asians were second class citizens and all the negative associations with being foreign. She wanted to be like the cool kids. She says, “It wasn’t until I was in my forties that I realized that I had grown up holding myself to standards I could never have achieved and role models that I could never have emulated.”

Reading How This Book Got Red

Greanias hopes readers of How This Book Got Red will feel empowered to write their own stories and to know that someone will relate to them or gain a new perspective from them. Also, readers can look at how Gee supports Red and works to be the same kind of friend.

Greanias hopes readers of How This Book Got Red will feel empowered to write their own stories and to know that someone will relate to them or gain a new perspective from them. Also, readers can look at how Gee supports Red and works to be the same kind of friend.

More deeply, Greanias hopes that young readers and their adults will consider how the lack of representation in books and popular culture affects real people. She says, “I hope they make an effort to find and consume books, TV shows, movies, music, and pop culture that include positive role models who look like them especially if a narrative centers on them. Because even though these are more common today than ever before, they are still a small fraction of what’s available.”

Because this “why” of the story is never explicitly stated, Greanias recommends that parents and teachers approach the “why” by looking more deeply at two particular illustrations — the two town scenes–one in the beginning/middle and one near the end of the book. Afterwards, ask children what they think the differences are between the two. What do they think is the reason behind the differences?

Greanias believes such an examination of Melissa Iwai’s illustrations will open a conversation about why representation matters; what young readers can do if they don’t feel represented; or what those who are represented can learn from Red’s experiences.

Greanias’s Approach to Writing

Greanias was a math kid who liked the certainty of the subject. The subjective nature of writing made it harder to know if her work was “right.”

“I had tremendous writer’s block as a younger person (and I still do today)! I wanted my writing to not only be right, but genius,” says Greanias. “But usually what came out on the page didn’t match what I’d hoped. The pressure of writing that first hooky sentence is enough to cause writer’s block! Plus, writing required creating something out of thin air, and the blank page was very intimidating.”

Starting a writing project is daunting for Greanias. To ease the anxiety, she often takes notes before approaching the blank page to formulate her thoughts first. Then she dives in knowing that initially her work will be imperfect. “Things still may not turn out how I envision them, but that’s okay.” Not having the expectation of perfection relieves the pressure. Plus, she knows revision is in front of her.

And something else helped – the prompts and deadlines she experienced in that final college semester creative writing class. Outside a library-run writing contest in 4th grade, the only writing Greanias had experience with were essays for school. She says, “Having assignments and due dates gave me enough structure so I did not spend my time paralyzed with indecision about what to write yet enough freedom from the right and wrong of essays to write from the heart. It was exhilarating. And even reading those old assignments which I’ve kept to this day, I am amazed at the writing I was able to create.”

And then there was a leap to becoming an author of picturebooks. “As a kid (and even still as an adult), I loved picturebooks–escaping into a story to live out imaginary scenarios that I would likely never get to experience in real life–and the beautiful art that drew me deeper into the stories. When I had kids of my own, my most treasured times were reading picturebooks with one (or two) of them in my lap and talking about the stories. My love of the stories and form and how it is shared is what first drew me to writing for children.”

Greanias also says writing for children is a hopeful choice, one that allows her to delight and entertain them. Through her stories, children might be inspired and empowered to be their best selves. “Plus, young readers are awesome! They have such great imaginations and I love their willingness to go along with stories no matter how wacky!” she says.

For Greanias, speaking directly to young readers is key and keeps the reader in mind throughout the process. This includes reconnecting with her childhood self and what would have appealed to her and connecting with her own children and what they were like at particular ages. She applies this perspective to craft how her characters might think, feel or behave in the situations they face.

Reader Interactions

As with most author visits, a successful school visit for Greanias includes preparing the students by having them read her books and learn a little about her before she comes. Then the school can foster enthusiasm around the visit. Specifically, teachers can encourage students to listen with an open mind and volunteer to participate and share. Teachers can even send their students’ questions to Greanias in advance.

Not only does this result in a good school visit for her, but it also leads to positive interactions that can sometimes be profound and sometimes pure fun. For example, during a read aloud of Amah Faraway for World Read Aloud Day, a student proudly stated that they speak Mandarin.

Later, the teacher told Greanias that student was typically quiet and had never told anyone they speak Mandarin.

Another time, Greanias used Hooked On Books as readers’ theater. With so many characters having bits of dialogue, she had ample opportunity to enjoy hearing the young readers perform in their unique voices and see their reactions to the dialogue as well.

Greanias shares that “having readers tell me that the story I wrote is their story is one of the sweetest things I could possibly hear.” Readers can look forward to more picturebooks and possibly a middle grade novel from Greanias, who has made time to take a writing course with author and poet, Renee LaTulippe.

Authors’ Corner is a periodic profile featured on our blog where authors discuss their writing process and the importance of school visits. Worlds of Words frequently hosts these authors for events in the collection. To find out when we are hosting an author, check out our events page. Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m.

- Themes: How This Book Got Red, Margaret Chiu Greanias, Rebecca Ballenger

- Descriptors: Authors' Corner