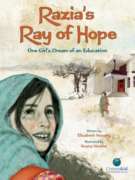

Razia dreams of getting an education, but in her small village in Afghanistan, girls haven’t been allowed to attend school for many years. When a new girls’ school opens in the village, a determined Razia must convince her father and oldest brother that educating her would be best for her, their family and their community.

- ISBN: 9781554538164

- Author: Suneby, Elizabeth

- Illustrator: Verelst, Suana

- Published: 2013

- Themes: education, School, village life, Women and girls

- Descriptors: Afghanistan, Awards, Canada, Intermediate (ages 9-14), Middle East, Picture Book, Realistic Fiction, USBBY Outstanding International Book

Razia’s Ray Of Hope

Reading The Breadwinner and exploring Razi’s Ray Of Hope have tugged some serious heart strings for me. There are days when I go to work and am exhausted from the day, but must attend graduate classes that evening. I look at it as a disservice, but how lucky am I to have the opportunity to attend a Master’s program? Not only do I have the opportunity to be a graduate student, but I was able to choose the college that I wanted to attend.

It never dawned on me that there are girls in the world that are not as fortunate. I knew there were places that limited opportunities for women, but until it was put in front of me, I never thought of it. It is hard to imagine living in a place where women are confined to houses because it is shameful for them to be out within the town. After pondering my own ignorance, I wondered if my students ever thought of this. If they knew there are places in the world where education does not come so easy and choice is something only men know about…..

This book could be used in the primary grade health classes to discuss the lack of nutrition Parvana and her family faced from only eating bread or often not eating at all.

Grace Klassen

As a teacher burning to instill a passion for learning in the hearts of my seventh grade students, Razia’s Ray of Hope: One Girl’s Dream of an Education offers a perfect picture of this passion personified. Author Elizabeth Suneby found her real life inspiration in Razia Jan, an Afghan teacher who opened a school for girls outside Kabul in 2008. The book’s heroine, also named Razia, portrays a quiet determination to attend school and “to be the kind of woman her grandfather Baba gi described- a woman who helped others through her work inside and outside her home.” She models the drive and purpose of courageous women pursuing an education around the world, often under duress. The emotional roller coaster ride this young protagonist endures as she waits for permission from her family to pursue her dream to enter the red doors of the new school in Afghanistan, left me wondering. How it is that many children in our schools take their own opportunities for granted when children around the world are left yearning to learn?

So I asked my students to reflect on three simple questions before we read this picture book: Why read? Why write? Why learn? And as we read Razia’s story together, they found gems of textual evidence to deepen their initial answers. The bell of inspiration rang when the teacher spoke, “If men are the backbone… then women are the eyes of our country. Without an education, we will all be blind.” When Razia’s grandfather advocated for Razia’s future at the men’s decision-making meeting, the truth rang out again, “It is time to give our daughters and granddaughters the chance to read and write. Our family and country will be stronger for it.” One group of students then chose to weave words from Suneby’s text into a “found poem” expressing the power of learning in their own lives. Another group illustrated the poem poster with compelling images from Razia’s world (the red door of the school, newspaper scraps, the medicine label, and colored pencils on a school desk) along with contrasting images from our school (a tablet, a science lab, a marquee with our mascot and a map). Their powerful poem presentation earned a round of applause from classmates and made my heart glad to see the ray of hope shine publicly.

Charlene Klassen Endrizzi

Grace, from my college teacher lens, I kept returning to the depressing label – hegemony – to capture the tough reality of this young girl’s existence. Razia’s confining life in Afghanistan made me consider the dominating forces in my life. Growing up in our deeply religious home, I felt restrained, as Razia felt controlled by her father, grandfather and older brothers. For me, higher education offered a way out, an avenue for looking beyond our limited perspective. Elizabeth Suneby’s empowering narrative explains the potential of educating girls – as a path to a more rewarding existence. Razia’s soon-to-be teacher implores the men in her family with these words: “I ask for your tolerance for Razia’s education… Without an education, we will all be blind.”

I long for an education without blinders in our nation. With the current emphasis on high stakes testing and curricula controlled by standards, it is no wonder that many U.S. students dream of the day they will escape the classroom walls. The spark of hope and empowerment Razia longs to find when she enters school offers a contrasting lens for critical conversations with teachers and students as we consider the value of education.

On a different note, Suana Verelst’s rich illustrations added depth to my understanding of the Middle East terrain. Characters leapt to life through her use of mixed media including fabric, photos and drawing. Next semester, I believe my preservice teachers will find this text a useful introduction to The Breadwinner by Deborah Ellis, an equally weighty historical narrative set in Afghanistan.

Grace Klassen

Charlene, I found another picture book, This Child, Every Child, both an informative and disturbing book for my middle readers. David Smith’s expository text highlights the uncomfortable contrasting conditions that exist for children whose basic rights are often fleeting or nonexistent. He deepens the experience with narratives of individual children whose stories illuminate these stark realities. Shelagh Armstrong’s beautiful illustrations give the viewer opportunities to visualize the truth concretely and to develop appreciation for the richness in our privileged western world of plenty. Building empathy for children struggling for basic rights is the higher outcome.

At the beginning of our classroom inquiry into Children’s Rights: Workers and Activists Around the World, I challenged my middle school readers to consider the basic questions addressed by the United Nations Convention in 1989, “What are the rights of children?” “What problems face children in our world today?” We used the Problem/Effect/Cause/Solution structure as a framework for thinking and This Child, Every Child offered a plethora of evidence that informed us and offered hope for change. The excellent conclusion, “Learning More,” is a springboard of questions, prompts and activities that propelled further thought, promoting an activist mindset.

All readers may appreciate an earlier book for the younger set, For Every Child, published by UNICEF in 1989 and again in 2001. Both versions of this picture book focus on simple principles from the UN Convention’s “Declaration of the Rights of a Child” first published in 1959. Each principle is gorgeously illustrated by a different well-known artist and bears close scrutiny. I asked students to examine each art panel and determine which “right” it demonstrated before displaying the matching text on the page. This close “reading” of the art led to animated conversations and prompted deeper questioning about the topic, pairing beautifully with Smith’s text.

Charlene Klassen Endrizzi

Grace, education as a ray of hope for change and a better future resounded in your seventh graders’ work. Heroes throughout our Workers and Activists texts this month like Iqbal Masih and Eel and she-roes like Malala Yousafzai, Sylvia Mendez and Razia treasured learning. It seems fitting to conclude by mentioning two books highlighting Middle Eastern librarians today, who took risks to save their irreplaceable warehouses of knowledge in the midst of war.

Hands Around the Library: Protecting Egypt’s Treasured Books, by Susan Roth, depicts the 2011 national protests in Cairo to oust President Mubarak. Thankfully protestors joined librarian Ismail Serageldin to protect one of their nation’s treasures, the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, during the riots. In a nearby country, a quiet librarian in Basra, Alia Muhammad Baker, took matters into her own hands in 2003 during the Invasion of Iraq following 9/11. With the library in harms way, Alia and her friends moved approximately 30,000 volumes out of the library, thereby saving another nation’s treasure-trove of books. Jeanette Winter’s The Librarian of Basra: A True Story from Iraq, offers a simplified perspective on this war torn country which can spark an exploration into the on-going Middle East conflict.

I hope resilient real-life and fictional characters like Malala, Iqbal, Eel, Sylvia, Razia, Ismail and Alia inspire teachers and students to examine how children can actively work to create a more just society tomorrow. I must express my deep appreciation to authors like Jeanette Winter, Deborah Hopkinson, Duncan Tonatiuth and Elizabeth Suneby for leading learners toward questions like, How can I make a difference?