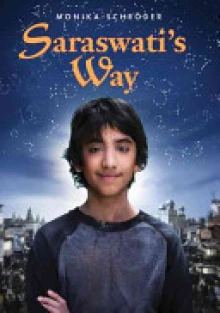

Saraswati’s Way

Written by Monika Schröder

Farrar Straus Giroux. 2010, 224 pp.

ISBN: 978-0374364113

Sometimes a short trickle of rain speckled the ground enough to give off the promising smell of wet mud. But after this cruel teaser the sky didn’t open up for a rain downpour, gave no relief from the sticky heat that hung unchanged, like a punishment with no end in sight (p. 8).

With poetic propose, Monika Schröder tells the story of people and fields in Rajasthan, India suffering from drought and the resulting impact on the academic aspirations of twelve-year-old Akash. The family’s crop will be too small to feed them all or pay off their debts to the landlord. But each day poor and motherless Akash looks into the eyes of Saraswati, goddess of wisdom and knowledge, and wishes to learn more mathematics. His teacher, Mr. Sudhir, has taught him all he knows and now Akash must find a scholarship or another way to pursue his education. Although Akash’s father Bapu believes in the boy’s dream to develop his gift for numbers, Dadima, his grandmother, says there is no need “to teach a bucket to sing” (p. 18). “Dreams are like air. They don’t feed our stomachs” (p. 20).

When Bapu succumbs to a fever, Akash holds fast to his father’s dying words: “What you desire is on its way” (p. 28). But it doesn’t seem that Ganesha, the remover of obstacles, is working on the boy’s behalf. Instead of insisting that Akash’s uncle overcome his drug addiction and take up work to support the family, Dadima makes a deal with the landlord to indenture Akash into hard labor at the quarry until the family can pay off its debts.

Still, Akash holds onto his dream; he stuffs his math notebook into his bag as he is forcibly transported to perform hard labor. When an opportunity presents itself, Akash examines the payment book used to record the workers’ wages. He uses his number sense to learn that none of the indentured workers will ever be debt-free. Knowing his work cannot help his family and determined to pursue his dream, Akash hops a train in order to make his way in the big city of Delhi. There he meets other desperate children who sleep on the streets and must pay off the police in order to make their living off travelers passing through the train station. One of them, Rohit, introduces Akash to Ramesh, the newspaper seller, who lets the boy work in his stall and sleep each night on the stall roof.

Finally, Ganesha removes all obstacles, and no one is more grateful than the boy on whom “trouble hangs… like a bad smell” (p. 95). A doctor who fixes Ramesh’s broken arm helps Akash meet the principal at the St. Christopher School. In five months, the boy will sit for the math exam with the goal of earning a scholarship. Readers will infer a positive future for Akash and wish for this resourceful boy’s hard-won success.

In this character-driven story, Schröder sets an emotionally-intense tone that clearly conveys the desperate situation of India’s poverty-stricken rural families and urban homeless children who must survive through any possible means. Hindu cultural beliefs create the context for the story and are thoughtfully and respectfully conveyed. More than superficial aspects of culture, readers learn about the roles of various gods and goddesses in the daily lives of Hindu people. The centrality of the Ganges River in Indian life, the Hindu cremation ceremony and mourning period, signs of respect exchanged between generations, and more are woven into the plot and authenticate the setting and conflict. The Vedic mathematics system is also explained and will intrigue readers who have not used these math operations shortcuts.

Monika Schröder, who grew up in Germany, has taught internationally in several countries and most recently has served as an elementary school librarian at the American Embassy School in New Delphi. In her author’s note, she talks about the impact of poverty and child labor on children in India. She says that street children have a slim chance of success in life, but wanted to write a hopeful book. In Akash, she has created a determined and courageous boy with strong religious beliefs, who earns a bit of help from others and experiences more than a small amount of luck in order to achieve his goals.

This middle grade novel can be paired with other books rich in cultural contexts in which young people strive to get an education. In Keeping Corner by Kashmira Sheth (2009), twelve-year-old Leela, a child widow living in Gujarat, India, in 1918, must “keep corner” after her young husband dies. During her one year confinement, her school teacher comes to Leela’s home prepare her for her scholarship exams and to raise the young girl’s consciousness about Indian traditions and politics. Wanting Mor by Rukhsana Khan (2009, see WOW Review Vol. 2, 2) tells the story of Jameela, an orphaned girl who against great odds succeeds at getting an education in Afghanistan. Three Cups of Tea: One Man’s Journey to Change the World… One Child at a Time (The Young Reader’s Edition) adapted by Sarah Thomson (2009, see WOW Review, Vol. 2, 1) from the adult book by Greg Mortensen and David Oliver Relin recounts how an elder, a mountain climber, and a village work together to make formal education a reality for young girls in Pakistan. In Home of the Brave by Katherine Applegate (2007), a young Sudanese refugee named Kek finds kindness and experiences racism in his fifth-grade ESL classroom in the United States. All of these books offer views of students’ yearnings and struggles for learning through formal schooling.

Judi Moreillon, School of Library and Information Studies, Texas Woman’s University, Denton, TX

WOW Review, Volume IV, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/review/reviewiv1.