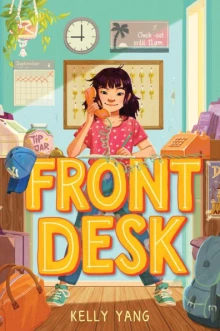

Front Desk

Written by Kelly Yang

Arthur A. Levine Books, 2018, 286 pp

ISBN 9781338157796

News that her family will be immigrating from China to America, where, her parents tell her, people can live in a house with a dog, eat hamburgers, and "do whatever they want" (p.1), sounds good to 10-year-old Mia. Mia's experience in America, however, is significantly different from what her family imagined. Instead of a dog, poverty welcomes Mia's family and stays with them for a long time. In the summertime, they live in a car with a broken air conditioner, making life unbearable. Their financial condition grows worse when Mia's mom loses her waitressing job. Eventually, Mia's parents find motel management jobs at the Calvista Motel where the family is allowed to live. It is like getting free rent, but their room is so close to the front desk that Mia's family are nearly on 24-hour duty. Mia works at the front desk while her parents take care of other tasks such as housekeeping and laundry.

"It’s just so unfair," I said. My mother sighed. She walked over and put a hand on my shoulder. "We're immigrants," she said. "Our lives are never fair." (p.68).

The hotel owner is Taiwanese-American Michael Yao and his son Jason is one of Mia's new classmates. Mr. Yao is infamous for his greed, selfishness, arrogance, and rudeness. His unreasonable orders make life stressful and challenging for Mia's parents. Mr. Yao symbolically displays the classic cliché that America is the land of opportunities. Prevalent racism against black people is also widely reflected when Mr. Yao and a security guard from a neighboring motel state that Blacks are "bad people." Thus, Hank, a weekly guest at the motel, becomes the suspect of a stolen vehicle. Many socio-cultural, socio-economic, and political issues of 1990's America are revealed through Mia's narrative.

This is an historical narrative that focuses on Chinese immigration set in the 1990's when many highly educated Chinese people left China due to the post-cultural revolution crisis. However, the social issues from that time period in America in respect to immigrants, people of color, poverty, and school bullying are very contemporary. When the school teacher displays a picture of Qin Shin Huang, a Chinese emperor, Mia thinks, "I don’t know where Mrs. Douglas got her picture from, but Qi Shi Huang's eyes were ridiculously slanted. His eyebrows went all the way up to his forehead" (p.87). Such ethnic stereotypes have not disappeared in today's America. Mia's cross-cultural friendship with Lupe, an immigrant from Mexico, sends a positive message, developing empathetic connections between them around each other’s transnational identities.

Mia is wise, insightful, clever, reflective, brave, and most of all, she displays agency. She is a relatively new Chinese immigrant child, but she resembles an American child. More accurately, Mia's perspective seems more Chinese American than Chinese immigrant. She is more vocal and clever than most of the adults in the story. Such confidence and street smartness are difficult to develop in the short time period projected within the book. However, Mia is capable of reaching out to different grown-up characters who she thinks or feels need her help. She is not shy around adults, including policemen. Given that the family immigrated in the 1990s, it would make more sense for the family, including Mia, to feel uncomfortable and fearful around government authorities. Government controls are one of many reasons that people left China after the cultural revolution. In Front Desk, Mia doesn't show any hesitancy to call and even assert her opinion in defending Hank with the police. Mia is like a nice adult in a child's body.

While Mia introduces herself as relatively new to America, and her English (C- level) is not yet as good as native English speakers, the way she solves problems does not indicate the language barriers of a new immigrant. Mia's oral accent is barely present in the entire story. Actually, she is interpersonally confident in communications. Mia isn't afraid of talking on the phone and it is easy to forget that Mia has been in the U.S. for only a couple of years. Mia's mom is self-conscious in respect to her poor English skills/pronunciation, which is more realistic.

Kelly Yang reveals Mia's immigrant identity through her written English. Mia writes several letters to help solve problems for other people. In the text, the author shows Mia's editing on those letters, but the English word confusions are closer to native English speakers' language confusions than Asian language speakers. Contrasting the English mistakes made by Mia to a Vietnamese refugee child in Inside Out and Back Again (Lai, 2013) shows that Mia's English confusions are from lack of knowledge about vocabulary and not inexperience of language usage.

Front Desk explores a variety of sub-themes including activism, family, school bullying, friendship, and racism. It can be paired with other books such as Inside Out Back and Again (2013) by Thanha Lai, Pandas on the Eastside (2016) by Gabrielle Prendergast, Insignificant Event in the Life of a Cactus (2017) by Dusti Bowling, The Way Home Looks Now (2015) by Wendy Wan-Long Shang, and Forest World (2017) by Margarita Engle. Lucy and Lunh (2014) by Alice Pung portrays an Asian teenager's perspective of her immigrant parents' hard-working life in Australia. Pandas on the Eastside (2016) and The Way Home Looks Now (2015) would be informative to explore language and cultural diversity among the group of people whom mainstream readers call "Chinese."

Author Kelly Yang signals that the story is somewhat autobiographical, based on when she helped her parents work at different motels in California. In the author's note, Yang provides historical information about Chinese immigration including that China's per capita GDP was only US$317 in 1990 and in that time 536,000 immigrants from mainland China came to the U.S. While the author's note is informative, the ambiguous timeframe in Front Desk may mislead young readers in thinking this is the harsh reality of current Chinese immigrants.

Kelly Yang is the author of three children's books and a columnist for the South China Morning Post. Yang's college entrance at the age of 13 and acceptance into Harvard Law School at the age of 17, making her one of the school's youngest graduates, add to her remarkable history. Currently, she is running KYP (Kelly Yang's Project) where she does curriculum development, teacher training, and work with children writers across various age groups.

Yoo Kyung Sung, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque NM

WOW Review, Volume XI, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/volume-xi-issue-1.