By Susan Corapi

Learning a new language can be fun depending on how it is taught and the circumstances that are prompting a person to take on the task. Immersion style language learning, when an immigrant is thrust into a new cultural context, is a different matter. It is stressful. It is incredibly tiring. It can also discombobulate a person’s sense of identity, which for many of us is partially anchored in language and the ability to communicate. When that ability to express feelings, ask for what we want, or simply pass the time of day is stripped away, we begin to wonder who we are.

I speak from personal experience on three levels. My family moved to France when I was ten years old. I remember the discouragement and frustration as I struggled to learn to communicate in French with my new teacher and classmates. I also observed the same emotions in my husband and children as they struggled to communicate with colleagues and friends when we lived in France for several years. Later, as a French Immersion teacher in Canada, I noticed the stress levels rise as my English-speaking primary students went through the early disorientation of learning in French. For these reasons our focus in this week’s blog is on bilingual books because they can support refugee and immigrant students in several valuable ways as they learn to communicate in a different language.

Multimodal Books are Bilingual Books

Before looking at specific books, I want to stretch the definition of bilingual books to include picture books, graphic novels, books written in side-by-side languages, and books with inserted words in different languages. I think of bilingual books as multimodal forms of communication. In that sense a picture book is a bilingual book because it is using word-based and image-based texts to communicate with the reader. Picture books are invaluable tools for language learning, which is another reason why the wordless books we looked at last week are so important to have in a classroom or library.

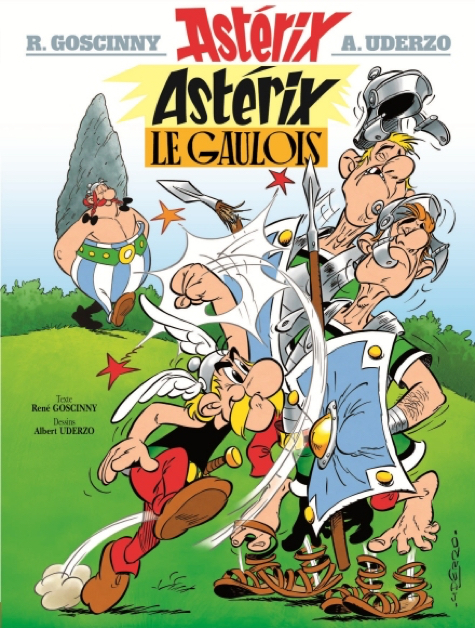

Astérix le gaulois by René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo

One multimodal bilingual text requires the use of touch. In The Black Book of Colors by Menena Cottin and Rosana Faria (Venezuela), young Thomas uses Braille, English and embossed illustrations to try and explain colors. For example, he describes yellow as “tasting like mustard but as soft as a baby chick’s feathers.” All the pages are black except for the printed white English text, so the reader has to read the Braille and the illustrations through touch.

Bilingual Books = Side by Side Languages

A more common format of bilingual texts are books with side by side languages. They can be effective language learning tools because the reader can go back and forth between the known language and the unknown one. Using these books also communicates that teachers and librarians place value on other languages that are spoken in the community. The placement of the language on the page is important to notice. Which language is placed at the top or on the left? Look for materials that place languages on more of an equal footing on the page. A few wonderful examples are profiled below.

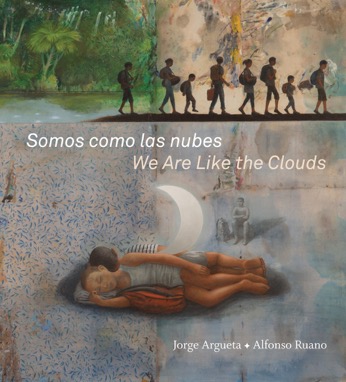

Somos como las nubes / We Are Like the Clouds by Jorge Argueta and Alfonso Ruano

Stepping Stones: A Refugee Family’s Journey by Margriet Ruurs and Nizar Ali Badr (Canada and Syria): Lauren Freedman introduced this book in December’s blog. The text is written in Arabic and English (though the page-turns use a left-right front-back sequence) and tells the story of a family’s hard decision to leave all that they know and love and seek refuge in another country. While the book does not dwell on the hardships of the journey, though it mentions that people lost their lives at sea, it does communicate the difficulty of leaving all that is familiar and creating a new sense of home in a new country. Some of the proceeds from sales of the book go to refugee resettlement organizations in North America.

Bilingual Books = A Resting Place

Bilingual books are wonderful for refugee and immigrant children because they can give them a bit of mental rest after an exhausting day of trying to learn new words, new rules of conduct, and a new culture. They are, in a sense, a watering station after a race. English language teacher Dr. Christina Igoa (The Inner World of the Immigrant Child, 1995) advocates letting students use the last 30 minutes of the school day to read books or listen to recordings in their own language because they need that mental rest.

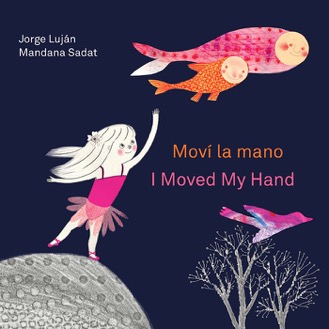

Moví la mano / I Moved My Hand by Jorje Luján and Mandana Sadat

Moví la mano / I Moved My Hand by Jorje Luján and Mandana Sadat (Argentina and France) is a poem written in both Spanish and English, so it can provide that mental resting place. But it can also transport the reader into an imaginative world that serves as a sort of time/space warp that is a break from the challenges of the real world. A young girl dances in her living room to an appreciative parental audience. As she moves her hands and body, she magically creates wonderful imaginative images.

Language Loss

One of the downsides to bilingualism is first language loss. As children become more skilled in the second language they may lose fluency in the first language. Bilingual books can keep both languages active in children’s minds so that they add the new language (additive bilingualism) instead of replacing the first language with the second (subtractive bilingualism).

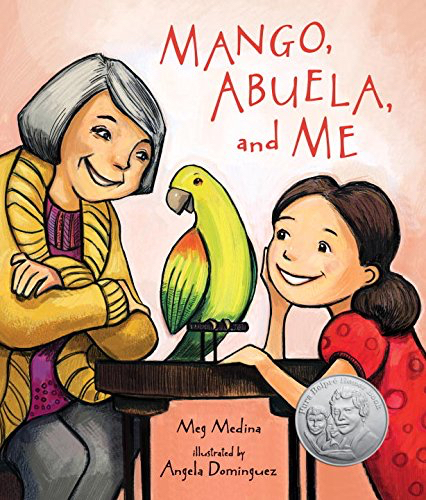

If a child loses fluency in the first language, communication with extended family can become challenging. A book that portrays the communication between grandparent and grandchild who do not share a common language is Mango, Abuela, and Me by Meg Medina and Angela Dominguez (USA). The author inserted Spanish words into the English text. The result is an introduction to some Spanish vocabulary while reading a story about communicating across two languages. Mia and Abuela go from having “mouths as empty as our bread baskets” to “mouths full of things to say.”

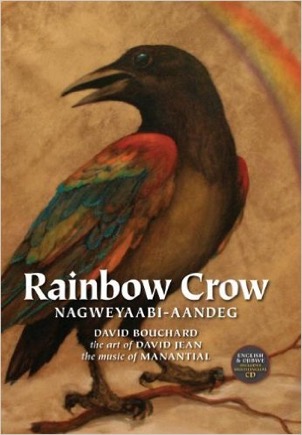

Rainbow Crow by David Bouchard and David Jean

Next week we will look at supporting refugees through narratives with strong characters who take action.

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday through Friday 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., Saturday 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. Check out our two online journals, WOW Review and WOW Stories, and keep up with WOW’s news and events.

- Themes: Susan Corapi

- Descriptors: Books & Resources, Debates & Trends, WOW Currents