By Trevor Brohard, Saundra D. Trujillo, and Mary L. Fahrenbruck, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, New Mexico

Using YA literature in the Criminal Justice field is a relatively new approach to exploring criminology theories. Saundra, a Criminology/Criminal Justice professor, and Mary, a Language, Literacy and Culture professor, implemented YA literature into Saundra’s Criminal Justice graduate course, Race, Crime and Justice, to learn if this unique approach could extend students’ thinking about various criminology theories as they applied the theories to YA literature.

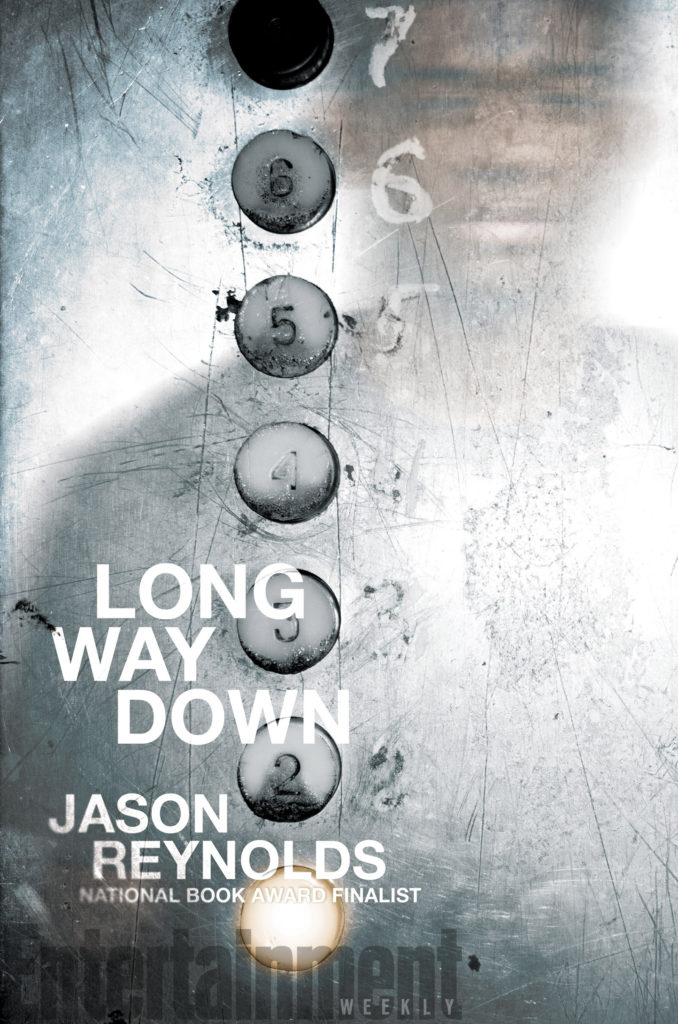

This week’s WOW Currents features Trevor Brohard’s reaction to Long Way Down by Jason Reynolds. Trevor uses a criminology/criminal justice lens to reflect on various criminology theories related to the intersections of race, ethnicity, crime, justice, cultural and structural contexts within the novel. Saundra and Mary reflect on Trevor’s reaction to close out this week’s post.

Trevor’s Reaction

National Book Award finalist, Jason Reynolds, dares the reader to peer through a window and witness the tragic street and gun violence common in predominantly Black communities across the U.S. William Holloman (Will) is faced with the decision to avenge the death of his brother or interrupt the seemingly never-ending cycle that has taken the lives of not only his brother but his father, many friends, and people he knew. Finding himself in an elevator, accompanied by the ghosts of others killed by gun violence, Will faces his choice to take revenge while his ghosts share their own experiences with gun violence and revenge. Through Will’s perspective, readers experience his overwhelming feeling of fear driven by his calling to follow the rules, knowing that this calling will, eventually, cost his life.

Will feels immense pressure from his ghosts to make the same choice (revenge) that his brother and father made before him. Reynold’s novel describes the influence of Social Disorganization Theory on crime. Social Disorganization suggests that the intersection of poverty, residential instability, and ethnoracial diversity interferes with a community’s ability to organize against social problems like violent crime. In other words, according to this theory, crime is more about characteristics of place than characteristics of people (see Kubrin & Weitzer, 2003). In places marked by social disorganization, barriers to the political economy, education, and opportunity for economic successes fuel cynicism and distrust of law enforcement thereby laying a foundation for what Anderson’s (1994) ethnographic work defines as a street code (see Kirk & Matsuda, 2011).

Reynold’s (2020) literary work presents a well-choregraphed illustration of life governed by the “Code of the Street” (Anderson, 1994) that is easy for any young audience to read with a little bit of time. As readers of Will’s story, we have a chance to feel the fear of being the one forced to pull the trigger, to feel the pressure of societal rules. Quite simply, the street code expects violence or the threat of violence as a normal response to slights, insults, and other shows of disrespect (Anderson, 1994). Reynold’s dramatization portrays the reality of living by street rules. Reynold’s novel opens a window that the reader can peer through to witness choiceful revenge. Readers are left with the questions, what would you do if you were in Will’s shoes? Would you break the cycle or repeat it?

Criminal justice scholars and practitioners can use this young adult novel as a window, or glimpse, into phenomena that can be examined through research. Although fiction, books such as Long Way Down (Reynolds, 2017) provide readers with truths and experiences of those whose lives are very different or might mirror their own. Reynolds’ novel offers a different lens, a different filter, into juvenile delinquency and the rational thought processes behind youth who feel forced to commit a criminal act. Researchers can pull from novel characters’ first-person perspectives, using details from narratives to identify topics and concepts worthy of closer examination. Young adult literature offers scholars the ability to shift into understanding crime events through the eyes of an offender or potential offender. This shift provides different angles that scholars can use to develop new conceptualizations related to crime, delinquency, and any rationale behind such behaviors.

Saundra’s Reflection

As Mary and I embarked on incorporating young adult literature into a heavily theoretical graduate criminal justice course (Race, Crime and Justice), Mary introduced me to Rudine Sims Bishop’s (1990) assertion that literature offers readers the opportunity to peer through windows of others’ lives, become a part of an imaginary world, or see our experiences reflected in the narratives. Bishop’s assertion also captures social scientists’ goal to contextualize human behaviors and experiences in ways that challenge us to confront social constructions that too often divide and threaten the values we claim to cherish. Reynolds’ novel led to seminar discussions centered on how stepping into Will’s world encouraged us to self-reflect on the power of environmental influence, accounting for context in our definitions of crime, criminals, and imagining each of our roles as criminologists and criminal justice professionals in influencing the world around us.

Using Will’s experiences, Trevor used Reynold’s poetic narrative to connect abstract criminology concepts and suggest theoretical integration. Trevor’s connection between Reynold’s novel and Anderson’s (1994) street code highlights criminology’s incomplete understanding of how a street code contributes to the racial disparity in U.S. firearm homicide rates. In 2019, the CDC reported that 16 in 100,000 U.S. Black males born in the year 2000 were killed in an incident of gun violence (56% of the firearm homicides for this age group); however, in 2019, the U.S. Black male population as a whole represented only 12% of the population. In comparison, white males in the U.S. under 20 years of age accounted for 26% of the firearm victims in this age group yet comprised 60% of the 2019 U.S. population.

Mary’s Reflection

The goal of reading is comprehension. Literacy educators know that readers’ background knowledge and prior experiences influence their comprehension of a text. Trevor’s reaction to Long Way Down (Reynolds, 2017) provides a clear example of the way his background knowledge of criminology theories helps him better comprehend the deep complexities of the novel. Trevor’s application of Social Disorganization Theory (Kubrin & Weitzer, 2003) and the Code of the Streets (Anderson 1994) frame’s his thinking about Will’s decision whether or not to avenge the murder of his brother. Trevor’s criminology background positions him to more thoughtfully answer his own questions; “…what would you do if you were in Will’s shoes? Would you break the cycle or repeat it?”

I think that if literacy educators shared criminology theories like Social Disorganization Theory (Kubrin & Weitzer, 2003) and the Code of the Streets (Anderson 1994) with students before they read Long Way Down (Reynolds, 2017), students would be better able to empathize with Will. They would be also be better equipped to discuss complex issues and to answer questions about the criminology aspects featured in the novel. Like Trevor, they will be able to more thoughtfully decide if they would break the revenge cycle or repeat it if they were in Will’s shoes.

We are interested in hearing about experiences in ELA classrooms. If you decide to use the resources in this post to support students’ discussions about Long Way Down (Reynold, 2017) in your classroom, we invite you to share your experiences in the Leave a Reply box below.

Young Adult Literature Cited

Reynolds, J. (2017). Long way down. Atheneum/Caitlyn Dlouhy Books.

References

Anderson, E. (1994) “The Code of the Streets”. The Atlantic.

Bishop, R. S. (1990). Mirrors, windows and sliding glass doors. Perspectives. 8(3).

Kirk, D. S., & Matsuda, M. (2011). Legal cynicism, collective efficacy & the ecology of arrest. Criminology, 49(2), 443-472.

Kubrin, C. E. & Weitzer, R. (2003). New directions in Social Disorganization Theory. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 40(4), 374-402.

NCHS Vital Statistics System for numbers of deaths. “2019, United States Homicide Firearm Deaths and Rates per 100,000: All Races, Both Sexes, Ages 0 to 19”. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC. United States https://webappa.cdc.gov/cgi-bin/broker.exe

- Themes: Jason Reynolds, Long Way Down, Mary Fahrenbruck, Saundra D. Trujillo, Trevor Brohard

- Descriptors: Books & Resources, WOW Currents

The criminologist’s take on Long Way Down by Jason Reynolds is thoughtful and compelling. It adds a fresh layer of understanding to an already powerful story. I appreciated how it blends personal expertise with empathy and respect for the author’s message.