By Kathy Short, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ

The increasing global mobility and multilingualism of our world are playing out in interesting ways in recent books for children. Some of these books focus on children learning to speak English or on English-speakers struggling to pronounce a child’s name. Still others naturally integrate multiple languages in a translingual book where characters weave additional languages into their dialogue, drawing from the multiple languages they speak and understand. Another trend is an increase in bilingual books with the entire text in two languages.

The increasing global mobility and multilingualism of our world are playing out in interesting ways in recent books for children. Some of these books focus on children learning to speak English or on English-speakers struggling to pronounce a child’s name. Still others naturally integrate multiple languages in a translingual book where characters weave additional languages into their dialogue, drawing from the multiple languages they speak and understand. Another trend is an increase in bilingual books with the entire text in two languages.

One intriguing trend is translingual books where the text is written in English, but in which characters naturally draw from the multiple languages they speak as they interact with each other. In I’ll Go and Come Back by Rajani LaRocca and Sara Palacios (2022), a young girl from the U.S. visits her grandmother in India, initially struggling to communicate since they speak different languages. As they interact, both gradually integrate each other’s languages of English and Tamil into their conversations. This book reflects a significant shift in not italicizing the non-English words, a common practice in translingual books. This practice is considered problematic because italicizing signals that English is the norm and marks non-English languages as “different.” The book also does not contain a glossary of Tamil words and phrases, taking the stance that the words are understandable in context, just as they would be in daily life, and so do not need to be translated. The decision to include a glossary varies with some translingual books including a glossary as an additional support for pronunciation and translation.

Authors and illustrators are finding creative strategies for integrating multiple languages into a book. In Alone like Me, Rebecca Evans (2022) integrates written Chinese characters in the notes exchanged by two lonely girls sending messages across apartment buildings. The story line is in English, but the illustrations display the notes in Chinese. The illustrations are in soft shades of blue and gray so that the red and yellow coats of the girls stand out as do their messages in red or yellow Chinese characters. In Luli and the Language of Tea by Andrea Wang and Hyewon Yum (2022), children in a preschool classroom who speak many languages come together around their shared love of tea. When one child invites them to tea, using the Chinese word for tea, each child replies by saying tea in their language. Their words for tea are written in the orthography of that language and are highlighted in color and italicized with the pronunciation in parentheses. The colors relate to maps at the end of the book to show where those languages are spoken. The color and italicizing in this case serve to celebrate multiple languages and orthographies.

Authors and illustrators are finding creative strategies for integrating multiple languages into a book. In Alone like Me, Rebecca Evans (2022) integrates written Chinese characters in the notes exchanged by two lonely girls sending messages across apartment buildings. The story line is in English, but the illustrations display the notes in Chinese. The illustrations are in soft shades of blue and gray so that the red and yellow coats of the girls stand out as do their messages in red or yellow Chinese characters. In Luli and the Language of Tea by Andrea Wang and Hyewon Yum (2022), children in a preschool classroom who speak many languages come together around their shared love of tea. When one child invites them to tea, using the Chinese word for tea, each child replies by saying tea in their language. Their words for tea are written in the orthography of that language and are highlighted in color and italicized with the pronunciation in parentheses. The colors relate to maps at the end of the book to show where those languages are spoken. The color and italicizing in this case serve to celebrate multiple languages and orthographies.

An especially intriguing book is A is for Bee: An Alphabet Book in Translation by Ellen Heck (2022). On each page is a letter of the alphabet with a surprising label, such as A is for Bee. Next to the bee are five words for bee that start with A, such as aamoo in Ojibwe and ari in Turkish. The featured animals are ones that English readers are used to seeing in alphabet books with the familiar pattern of A to Z, but the 69 words and languages included across the book provide many surprises for readers. An extensive Author’s Note explains the author’s complex decisions on how to represent these languages.

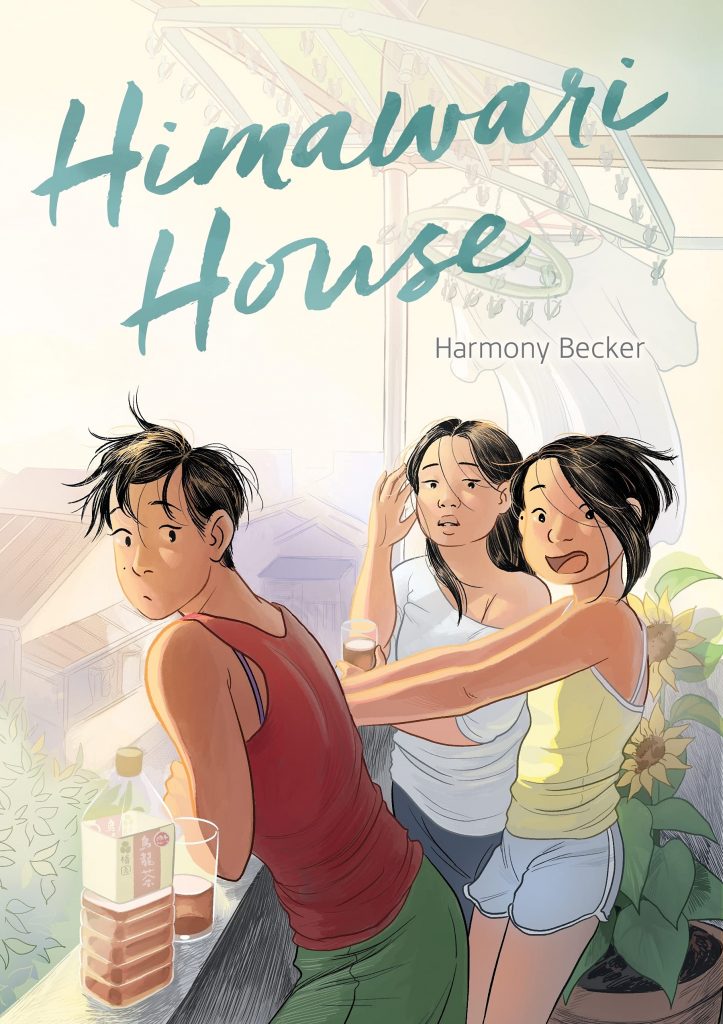

Himawari House by Harmony Becker (2021) is a fabulous example of a YA graphic novel that is bilingual and translingual. Five teens from different parts of the world are living together in a house as they attend a Japanese-language school in Tokyo. The graphic novel follows their changing relationships and identities. The speech bubbles are in multiple languages and reflect their language learning; for example, using blurred lines when the Japanese being spoken is not understood by a character or writing English phonetically when a character is speaking in accented English. Much of the dialogue is written bilingually in the speech bubbles to reflect the language being spoken by a character followed by a translation for the English reader.

Himawari House by Harmony Becker (2021) is a fabulous example of a YA graphic novel that is bilingual and translingual. Five teens from different parts of the world are living together in a house as they attend a Japanese-language school in Tokyo. The graphic novel follows their changing relationships and identities. The speech bubbles are in multiple languages and reflect their language learning; for example, using blurred lines when the Japanese being spoken is not understood by a character or writing English phonetically when a character is speaking in accented English. Much of the dialogue is written bilingually in the speech bubbles to reflect the language being spoken by a character followed by a translation for the English reader.

Another way that recent books highlight multilingualism is bilingual books, especially Indigenous picturebooks from Canada, such as Mii maanda ezhi-gkendmaanh/This is How I Know by Brittany Luby and Joshua Mangeshig Pawis-Steckley (2021). This picturebook about an Ashinaabe child talking about the seasons with her grandmother reflects a trend of placing the Indigenous language first on the page and English second. Many bilingual books, especially English/Spanish books, signal that English is the language of priority by placing English in positions of power on the page and in the title. This book also reflects efforts by tribal nations to maintain and revitalize their languages through books for children. The Immortal Boy by Francisco Montaña Ibáñez (2021) is a bilingual YA novel from Bogota, Colombia that tells the intertwining stories of two separate lives that come together. The book is organized in a flip-book style so the reader can decide which language to read in which order.

Language learning for new immigrants is a continuing focus in books for children, but with some shifts. The Day Saida Arrived by Susana Gómez Redondo and Sonja Wimmer (2020) reflects one of the few books in which two children learn each other’s languages. Typically, these books portray the immigrant child gaining a new friend who helps the child learn English, so that the learning is always one-sided. In this book, a new girl from Morocco, forms a relationship with another girl and both enjoy teaching their languages of Arabic and English and learning about each other’s cultures. The two languages float through the air and both alphabets are included at the end. The original languages were Spanish and Arabic since the book was originally published in Spain, so the translation involved translating text and images to move to English and Arabic.

Two noteworthy picturebooks focus on language learning from the perspective of the child who is an immigrant, rather than a child from a Western English-speaking culture. In My Words Flew Away Like Birds by Deborah Pearson and Shrija Jain (2021), a new immigrant finds that the English words she had already learned fly away when she moves to a new place. She also notes the assumptions people make about her as the “new” girl that are not true. Gibberish by Young Vo (2022) visually depicts a young immigrant’s experiences in a new country, with speech bubbles showing the gibberish that he hears instead of English. The people he interacts with appear as 1940s style cartoon figures. Gradually, the gibberish in classmates’ speech bubbles start to contain recognizable English words and their features become realistic in the illustrations. This picturebook is effective in conveying the uncomfortable experience of a new country and language as well as infusing humor.

Sometimes the language struggle is on the part of English-speaking classmates and teachers, rather than the immigrant, particularly in pronouncing names. In Thao (2021) by Thao Lam, a Vietnamese Canadian child tires of her name being mispronounced and decides to call herself Jennifer—until she realizes that her name connects her to her family. The Boy Who Tried to Shrink His Name by Sandhya Parappukkaran and Michelle Pereira (2022) is the story of an Indian Australian boy who knows that his long name, Zimdalamashkermishkada, will cause problems in a new school and considers shortening his name to Zim. In addition to pointing out the importance of English-speakers learning to pronounce unfamiliar names, the book also offers a strategy for pronouncing long names, in this case the boy adds another syllable to his name each time he introduces himself. By the end of the book, the reader can pronounce his name.

This focus on language and language learning brings a positive lens to multilingualism as a valuable resource for a person and for a community. Instead of viewing a new language as a problem, these books view multilingualism as a natural part of our world and an asset for the community. They challenge common stereotypes and provide new insights into language and identity.

Access our 2022 lists of recommended K-12 global children’s and YA literature, organized by grade level bands and themes with text complexity information and plot summaries for each book.

WOW Currents is a space to talk about forward-thinking trends in global children’s and adolescent literature and how we use that literature with students. “Currents” is a play on words for trends and timeliness and the way we talk about social media. We encourage you to participate by leaving comments and sharing this post with your peers. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit its archival stream.

- Themes: Kathy Short

- Descriptors: Books & Resources, Debates & Trends, WOW Currents