Codeswitching: Translation and Linguistic Issues

I don’t mind reading books that deal with code-switching because this is the way that I speak and other people do as well. (Paula) Students talk this way and we hear it just the same . Often, I don’t realize they even do it. (Chris) As Paula and Chris note, for many people codeswitching is a way of life. People hear codeswitching in their homes and communities. It is part of who they are. When people codeswitch as they talk, they aren’t randomly mixing languages, but using complex linguistic strategies for communication. Because codeswitching is ruled by a set of grammatical norms it is possible to codeswitch incorrectly.

When using codeswitching in writing, authors can play with these grammatical norms, just as authors play with language in monolingual texts. However, it is still possible for authors who are unfamiliar with the ways that people codeswitch in daily life to codeswitch in texts in ways that are awkward or inauthentic. For example, authors sometimes use a Spanish word, then immediately translate it into English. Such translations are often redundant for bilingual readers. While they may be useful for monolingual readers, this type of translation can make the text feel disjointed and unnatural.

Authors use various ways to mix English and Spanish. As a group of teachers explored a set of children’s books that codeswitch they noted the following:

- Some books included an English translation directly before or after the Spanish phrase.

“En un tiempo pasado,” Papá Grande began. “Once upon a time….on a windy night a man was riding a horse through a forest.” (from Tomás and the Library Lady)

- Some books used the word first in English, then later uses of the word were in Spanish.

“This is the pot that the farm maiden stirred. This is the butter that went into the cazuela that the farm maiden stirred.” (from The Cazuela that the Farm Maiden Stirred)

- Some books carefully use context (both textual and illustrations) to make the meanings of Spanish phrases easily understood.

“Abuelito takes me to the seashore. He loves to walk by the ocean. We sit on the pier and look down at the water. –Mira el pez grande—Abuelito says. He points to a big fish. –Me gustan los chiquitos—I answer, and show him some little silver fish that are nibbling by a rock.” (from I Love Saturdays y domingos)

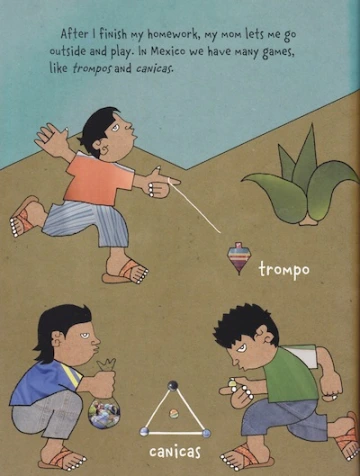

- Some books use the Spanish word in the text, but label the illustration with the English translation.

Children’s books that use codeswitching in authentic ways can help children explore the varied languages and dialects used in the real world.

For children who hear codeswitching in their homes and communities, these books show that their language is valued and that people like them have a place in literature.

Many thanks to Chris, Gracia, Anita, Selia, Ida, Mayra, Leslie, Irma, and Paula for their help with this blog series.

Editor's Note: Codeswitching in a global society has been further discussed by Janine Schall regarding its purposes and tensions in children's literature and holiday picture books.

Please visit wowlit.org to browse or search our growing database of books, to read one of our two on-line journals, or to learn more about our mission.

I had the nice opportunity to read about this article, which made me think about how important is to accept the bilinguism families, societies; that nowadays you can see that at home children are being raised with more than two languages, where they have a lor of code mixing or code switching. My question is, Do you think it is important for translators to be aware about Linguistic Racism? or How important is for translators to know about this in their daily work to not affect the readers (when they are part of translations)or to respect this language varities (which sometimes is an interference in translation? :D