Children's Literature and Strong Emotions During Civil Unrest

Multiple cities in the U.S. have been racked by civil unrest, whether the protesters are frustrated with racial inequalities, face mask policy or simply tired of the limitations of living in a pandemic. Children cannot miss hearing the strong emotions that are projected in the media or felt by adults as they eavesdrop on conversations. The resulting need is to help them think about these big events and the strong emotions that ensue.

While the previous three blog posts have been about just that--helping children think about strong emotions--this week I focus on the thoughts of children as they face civil unrest. What do children think of in the middle of unrest? What do they dream of? As adults working with children, these stories can give us a new focus for discussion as we hear about ways kids cope with stress.

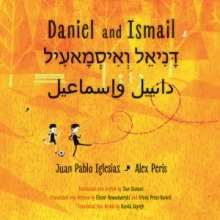

The Middle East is one part of the world that frequently experiences civil unrest. In an extraordinary trilingual book, translated from the original Spanish into Hebrew, Arabic and English, Chilean author and illustrator Juan Pablo Iglesias and Alex Peris tell the story of Daniel and Ismail, two boys who share a birthday. One is Jewish, the other Palestinian. They both receive a soccer ball and a scarf (a Jewish tallit and a Palestinian keffiyah), and they take both to the park where they meet for the first time and share a soccer game. They are so engrossed in the game that they lose track of time and, after dark, grab a ball and scarf and head home. They inadvertently grab each other's scarf and, when they arrive home and discover the mistake, they hear their parents' fears and stories of the "other" as they scold their sons for the mix-up. The boys meet the next day to exchange scarves, but then they go off and do what they do best--play soccer with no concerns of where each comes from.

European countries have been on the receiving end of many refugees from the Middle East and Africa. It is natural that European authors and illustrators would address the adaptation of children during civil unrest. Idriss and His Marble by René Gouichoux and Zaü is an example of what kids focus on in the middle of unrest. Idriss has to flee with his mother and what follows is a refugee journey that involves days of walking, an overcrowded bus, crawling under barbed wire, and finally a bribe for a ride on a leaky boat. Through it all, Idriss hangs on to the one thing he has from home--a marble. It is almost lost at sea when the boat is bumped by a coast guard vessel, but a fellow refugee does a miracle recover right before the marble sinks out of sight. Idriss arrives in his new home, and the marble becomes the mechanism that helps him make a new friend as he plays with his marble and meets a boy who shares a love of the game.

Using an object as a source of comfort and stability is illustrated in a similar story, Lubna and Pebble by Wendy Meddour and Daniel Egnéus. Lubna finds a pebble on the beach and cares for it like a doll. She uses her "friend" for play and as a comfort buddy while waiting in a refugee camp for a new home. When she and her father are assigned a new place to travel to and live, she passes her "friend" on to a new refugee as a source of comfort and stability.

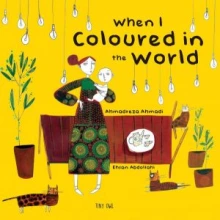

The last two books I profile are an interesting pair that describes civil unrest and other social issues through color. One book discusses the way color disappears in the dark world of civil unrest, while the other book talks about the color a child would add to the world to solve world problems like war, hunger, sadness and drought.

Vanishing Colors, by Norwegian author Constance Ørbeck-Nilssen and Norwegian-Turkish illustrator Akin Duzakin, uses words and images to describe the desolation of civil war. As a young girl waits for daybreak with her mother, she describes the colorless ruins of the deserted city in a conversation with a giant and wise black bird. As they wait for the dark of night to pass, the bird encourages her to reminisce about her past life with her father and friends. Beginning with her red dress, she remembers the colors of a life filled with family, friends and community celebrations. The girl wonders if she will ever see her father and friends again, but is reminded through a story of a flock of birds of the power of staying together with the few people she has left in her life. As the sun rises, splashing color all over the ruined city, the girl and her mother prepare to leave the city to an unknown destination but guided by a colorful rainbow bridge.

In a natural book pair, Iranian author Ahmadreza Ahmadi uses short poems to highlight an emotion and color describing what children would do to return peace and happiness to their world. The poems are illustrated in vibrant colors by Iranian illustrator Ehsan Abdollahi. Each page in When I Colored In the World takes on one problem, and the child narrator erases out the problem, replacing it with a color and something that changes the world. For example one page says "Hungar / I rubbed out the word hunger. / I wrote wheat with my green crayon. / Green / Wheat / I made wheat grow in fields all over the world. / I gave the world green." The final page expresses my hope. "Despair / I rubbed out the word despair. / I wrote hope with my yellow crayon. / Yellow / Hope / All over the world children smiled. / They ran into the fields and up the hills / looking at the beautiful new life growing all around."

I share the conviction of Italian illustrator Roberto Innocenti (Myers, 2009) when he says that children need to engage with the history that impacts them. These past few months they have watched their world change dramatically, and deserve the chance to talk about the emotions caused by all the changes as people they know die, basic necessities disappear or anger erupts. My hope is that the texts profiled over the last four weeks will help give families or classrooms a forum for discussions around the strong emotions tied to the big events they have experienced.

Reference Myers, L. (2009). What Do We Tell the Children?: War in the Work of Roberto Innocenti. Bookbird 47(4), pp. 32-39.

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit its archival stream.