By Kelly Weese, Saundra D. Trujillo, and Mary L. Fahrenbruck, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, New Mexico

WOW Currents for June will feature reactions to young adult literature from graduate students enrolled in the Criminal Justice Program at New Mexico State University. Using a criminology/criminal justice lens, students enrolled in Saundra’s Criminal Justice course, Race, Crime and Justice examined current young adult literature as a part of their studies. Saundra, a Criminology/Criminal Justice professor, and Mary, a Language, Literacy and Culture professor, were curious to learn if incorporating young adult literature could push students’ engagement with various theories and inspire creativity in students’ ability to apply criminology theories related to the intersections of race, ethnicity, crime, justice, cultural and structural contexts.

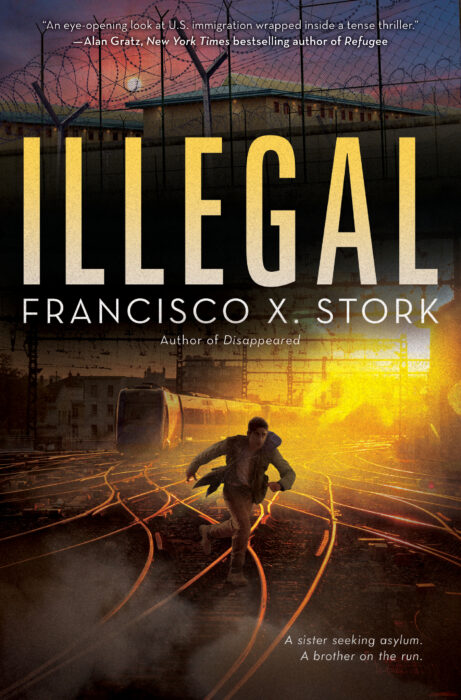

Saundra piloted this unique approach in her course using current YA literature that Mary suggested. Novels included Illegal. A Disappeared Novel by Francisco X. Stork, Long Way Down by Jason Reynolds, Punching the Air by Ibi Zoboi and Yusef Salaam, and Juvie by Steve Watkins. The narratives in each novel were informed by each author’s life experiences and by their research, resulting in novels that are rich with content directly connected to criminological theories on the causes and consequences of crime.

In this week’s WOW Currents, Kelly Weese shares his reaction to Illegal by Francisco X. Stork using a criminology/criminal justice lens. Kelly’s reaction incorporates research from the large body of scholarship on the Latin@ Paradox (see Sampson, 2008 and Barranco, Shihadeh, and Evans, 2018), social learning theory (see Giordano, 2020) and implicit bias (see Kahn and Davies, 2011).

Kelly’s Reaction to Illegal, A Disappeared Novel (Stork, 2020)

Illegal by Francisco Stork alludes to the many horrors often faced by immigrants at the U.S. southern border. Currently, at the nation’s southwest border, immigrants from Mexico are being held in U.S. detention centers for increasing amounts of time during a global pandemic (Massey, 2020; Mayorkas, 2021). Further, unaccompanied immigrant children arriving at the southern ports of entry are often met by militarized law enforcement; those without U.S. citizen family members are taken into the custody of U.S. Health and Human Services (Mayorkas, 2021), risking permanent displacement from their family (Massey, 2020).

The experiences, and often gut-wrenching decisions faced by Emiliano, the main character in Illegal (Stork, 2020), reflect those made by migrant youth today who flee the extreme violence of their home nation and seek refuge in the U.S. According to the Center for Disaster Philanthropy (2021) and the work of Massey (2020), U.S. residents’ perceptions of undocumented and recent migrants to the U.S. have been shaped by nativist propaganda often portraying migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers as dangerous criminals.

Ousey and Kubrin (2018) caution that there is no uniform relationship between immigrant populations by reason for migration or home nation and crime; rather most studies on the relationship between immigrants and crime find that overall, immigrant populations reduce crime in their communities (Ousey & Kubrin, 2018). Moreover, Massey (2020) finds that refugees and asylum seekers are the largest proportion of migrants currently held at the U.S. southern borders. Similarly, Stork’s characters Emiliano and his sister Sara, both fled cartel and gang violence only to be met with exclusion and isolation upon arrival at the U.S. border. Rather than define asylum seekers and other immigrants as criminals and people who should be feared, it is important that U.S. residents and students recognize asylum seekers and other immigrants as human beings – no different from themselves – deserving a fair chance to legally live in the U.S.

Often, popular movies and literature portray a dramatic image of immigrants as dangerous criminals. These portrayals make their way into public and political discourse as facts. U.S. public opinion is influenced by the information they receive through television, social media, or from books they read for entertainment (Mutz, 2018). Therefore, media can contribute to individuals’ implicit biases against immigrants and these biases are constructed by dramatized, often fictional or sensational, content (Mutz, 2018). For example, a movie like Sicario (Villeneuve, 2015) portrays Mexicans at the border as violent cartel members. This portrayal can fuel how individuals view the current border crisis and how we act/react to recent immigrants. In addition, people living in the U.S. can further attribute the shaping of their implicit biases against immigrants and asylum seekers to the history of colonialism and racism in the U.S. The reality is that many people currently trapped at the border fled the violence portrayed in media and seek asylum in a safer, new country.

In a young adult novel like Illegal (Stork, 2020) it is important for readers to identify with the characters; incorporating Illegal into young adult learning can encourage future generations to understand the struggles of immigration and the reasons why many migrants make very tough decisions. Despite sensationalized media, and anti-immigrant rhetoric, readers can learn to be discerning, ignoring coverage or dramatized criminal portrayals of immigrants wishing to join our communities. Illegal challenges youth to empathize and consider possible truths beyond what is presented by the media they consume. Learning to consider context, truth and fact–seeking are key components in critical thinking skills. Readers can be encouraged to use a book like Illegal as a springboard to think for themselves and do their own research.

Educators can use young adult novels like Illegal (Stork, 2020) to challenge the students’ pre-conceived notions of immigrant populations. After reading Illegal, students can conduct research on the southern border’s detention centers and then share their findings with classmates. Challenging students to consider their thoughts on immigration, then sharing how their thoughts were supported or refuted by their findings can encourage a dialogue of different perspectives of classmates. Similarly, criminologists can take advantage of narratives in books like Illegal to explore new avenues for theoretical development regarding immigration. Young adult literature like Illegal can promote a more humanitarian awareness of immigration issues and allow us all to question and learn through well informed literature. Instead of allowing biases influenced by the context of politics and fear to drive our understandings, young adult literature can help us discover truths and alternative perspectives that might otherwise remain unseen.

Saundra’s Reflection

The criminology/criminal justice discipline focuses on the causes of crime, consequences of crime, and systems of formal and informal social control. As an educator in higher education whose graduate students are often legal and law enforcement hopefuls or current professionals, I have often incorporated elements from popular cinema, television, and documentary films to illustrate and facilitate student engagement with key concepts and mechanisms in theories of crime and justice. Although students enjoy using popular media in classroom discussions and in online activities, I’ve always sensed that many students still struggle to truly learn the theoretical basics and, sheerly as a matter of course outcome expectations, turn to rote memorization of foundational theoretical materials that are quickly obtained and more quickly forgotten.

Admittedly, I was skeptical at first when Mary suggested incorporating young adult literature into a heavily theoretical criminal justice course. As I developed the syllabi, I wondered: How could a fiction novel, intended for a young adult audience add to a course like Race, Crime, and Justice? If I struggle to encourage the careful, intentional reading of criminology/criminal justice work that is so relevant to the policing and social justice issues today, how on Earth am I going to convince them to read fiction meant for young adults? Despite these initial hesitations, Mary and I jumped in full force. And, once again, the students became my teachers.

Incorporating novels like Illegal by Francisco Stork sent ‘light bulb moments’ through the students like the wave at a baseball game. Student engagement with the narrative of Illegal prompted many to genuinely seek out a deeper understanding of criminology and criminal justice theory on the constructions of crime, criminal labels, race, ethnicity, immigration, and justice. Discussions in class and online became deeper and more meaningful, far beyond the basic “have to learns” and toward “need to learn more”.

Mary’s Reflection

Looking at YA literature through a criminal justice lens is a new experience for me. When I read novels like Illegal. A Disappeared Novel (Stork, 2020), I often wonder about the intersection between identity, crime, race and justice. I will pause my reading to google the twists and turns in the plot to see if the author might have anchored some of them in actual facts and events. Even though my investigations enhance my transactions with the novel, I continue to feel as though I have only skimmed the surface of the story. This feeling surfaced many times while I was reading Illegal, especially during the scenes of Sara’s experiences at the detention center. I needed to understand and name the possible motives that the refugees, law enforcement officers and allies have to act and interact with each other in the manner that they did in the story. Participating in Saundra’s Crime, Race and Justice course with grad students provided me with a new lens to explore Illegal. The theories Kelly mentions in his reflections offered me the framework and language I needed to unpack and discuss the deeper complexities Emiliano, Sara, and the other characters experienced throughout the novel. As a result, I am better able to understand the characters, plot and themes in Illegal.

For those of you who enjoy reading YA novels, I highly recommend Illegal. A Disappeared Novel (Stork, 2020). Along the way, check out a few of the references Kelly has cited. If reading the novel with a criminal justice lens affords you a surprisingly new experience, let us know about it in the comments below. We would enjoy learning about your experience.

Young Adult Literature Cited

Reynolds, J. (2017). Long Way Down. Atheneum/Caitlyn Dlouhy Books.

Stork, F. X. (2020). Illegal. A Disappeared Novel. Scholastic Press.

Watkins, S. (2017). Juvie. Candlewick.

Zoboi, I., & Sallam, Y. (2020). Punching the Air. Balzer + Bray.

References

Barranco, R. E., Shihadeh, E. S., & Evans, D. A. (2018). Reconsidering the usual suspect: Immigration and the 1990s crime decline. Sociological Inquiry, 88(2), 344-369.

Center for Disaster Philanthropy (2021, April). Southern border humanitarian crisis. https://disasterphilanthropy.org/disaster/southern-border-humanitarian-crisis/.

Kahn, K. B., & Davies, P. G. (2011). Differentially dangerous? Phenotypic racial stereotypicality increases implicit bias among ingroup and outgroup members. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. 14(4), 569-580.

Massey, D.S. (2020). The real crisis at the Mexico-U.S. border: A humanitarian and not an immigration emergency. Sociological Forum. 35(3), 787-805.

Mayorkas, A. N. (2021, March 16). Statement by Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro N. Mayorkas regarding the situation at the southwest boarder. Homeland Security. https://www.dhs.gov/news/2021/03/16/statement-homeland-security-secretary-alejandro-n-mayorkas-regarding-situation

Mutz, D. C. (2018, April). Mass media and American attitudes toward immigration. Global Shifts Colloquium. Philadelphia, PA, United States. https://global.upenn.edu/sites/default/files/Mutz.pdf

Ousey, G. C., & Kubrin, C. E. (2018). Immigration and crime: Assessing a contentious issue. Annual Review of Criminology, 1, 63-84.

Sampson, R. (2008). Rethinking crime and immigration. Contexts, 7(1), 29-33.

Villeneuve, D. (2015). Sicario. Lionsgate: United States.

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit its archival stream.

- Themes: Francisco X. Stork, Illegal A Disappeared Novell, Kelly Weese, Mary Fahrenbruck, Saundra D. Trujillo

- Descriptors: Books & Resources, WOW Currents