by Mary Starrs Armstrong, University of Alaska, Anchorage, AK

This is not the conventional great-teaching-deep-cultural-exploration and learning-Rosenblatt-inspired-response entry. This is a what’s-on-my-mind, I’m-exposing-my-dismal, disappointing-failure entry.

Typically, teachers use non fictional texts to explore cultures within and beyond their students’ world, knowing the importance of gaining information as they their develop a global perspective of others from the outside in; however, we’ve found that getting acquainted with characters in story may open the world to children in ways expository text doesn’t. Enter biography, with its factual base and strong narrative style to function as a literary bridge between fiction and non fiction, and a cultural link between characters’ lives and environments and our children’s lives and environments.

Children connect with story almost on a visceral level. Similarly they are fascinated by the lives of others, especially if they have a cultural framework of the times surrounding that character. Young children ages 6 – 9 are at a critical time for social and attitudinal growth. Biography can provide rich examples of problems and solutions, challenges and strategies utilized by people in history and those who are our contemporaries.

The exploration of life and culture through biography is written about eloquently in Language Arts text books, Children’s Literature text books, heralded in break-out sessions at conferences, and read about in journals. Accounts bring to light successful, upbeat lessons with widely inspiring results.

We know that one way children learn about people’s lives is through biography. They can learn about culture and environment, perseverance and persecution through biography as well. Duthie (1998) writes, “Biography and autobiography are important components of lifelong literacy … open a door for reflection and discussion, and can satiate curiosities with positive resolve at a crucial time in their development.” Who argues? What better way to grow a global perspective of others?

Well, that’s what I’d like to know. Read on:

Continue reading →

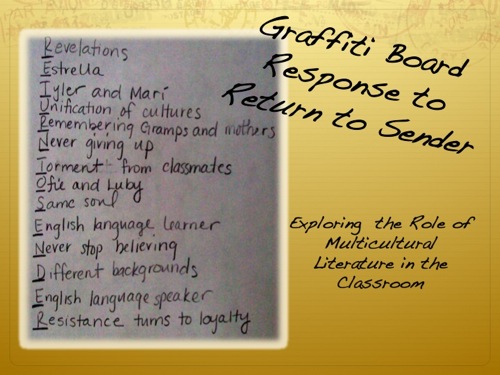

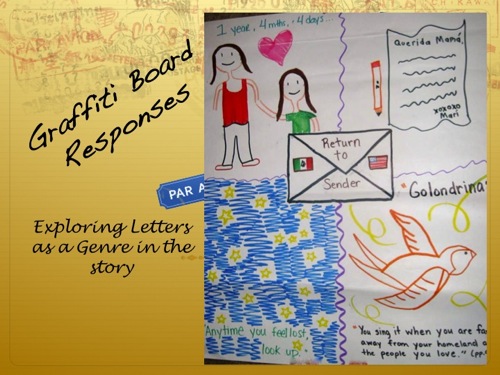

As teacher educators we believe we must engage future teachers in the important work of finding quality children’s and adolescent literature students they or their students might not find otherwise. We encourage students to read a wide variety of recent texts and discourage students from using overly popularized texts, not because we necessarily dismiss the quality of these texts, but because we believe that often texts with the richest possibility for critical, social, and intellectual richness may not be a part of the popular mainstream. Furthermore, we want to expose preservice teachers to texts that portray diverse groups that mirror the students with whom they will eventually work.

As teacher educators we believe we must engage future teachers in the important work of finding quality children’s and adolescent literature students they or their students might not find otherwise. We encourage students to read a wide variety of recent texts and discourage students from using overly popularized texts, not because we necessarily dismiss the quality of these texts, but because we believe that often texts with the richest possibility for critical, social, and intellectual richness may not be a part of the popular mainstream. Furthermore, we want to expose preservice teachers to texts that portray diverse groups that mirror the students with whom they will eventually work.

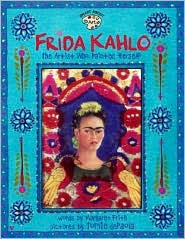

Reading biographies, studying the genre while having access to a variety of titles about the same person offers choice as well as opportunities for depth and exploration. Consider Elisabeta, a Mexican American fifth grader who did not see herself as a reader, who expresses surprise at the extent she got hooked on reading about the life and work of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo:

Reading biographies, studying the genre while having access to a variety of titles about the same person offers choice as well as opportunities for depth and exploration. Consider Elisabeta, a Mexican American fifth grader who did not see herself as a reader, who expresses surprise at the extent she got hooked on reading about the life and work of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo: