One country: Pakistan. Two children: Iqbal Masih and Malala Yousafzai. Each was unafraid to speak out. He, against inhumane child slavery in the carpet trade. She, for the right of girls to attend school. Both were shot by those who disagreed with them—he in 1995, she in 2012. Iqbal was killed instantly; Malala miraculously survived and continues to speak out around the world. She was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2014 for her work.

- ISBN: 9781481422949

- Author: Winter, Jeanette

- Illustrator: Winter, Jeanette

- Published: 2014 , Beach Lane Books

- Themes: Children, School, slavery, Survival

- Descriptors: Asia, Biography - Autobiography- Memoir, Pakistan, Picture Book, Primary (ages 6-9)

- No. of pages: 40

I fell in love with Iqbal by Francesca D’Adamo immediately. I am a lover of all books, just on principle. However, when I begin to recommend books to family and friends, they know it’s a fantastic book. Not only is Iqual an easy read, it is a book that will engage even the most reluctant readers. It’s short chapters are overflowing with characters that speak to your heart. They simply leap off the pages.

This book calls attention to a young boy who gave of himself bravely. He started a conversation that everyone needs to be having. Where are some of our imported goods made? Who is making them? Child labor has always existed. Here, we have a true first hand account, a primary souce if you will of this horrrible injustice that occurs around the world, many times over. The narrator of this book is a young girl named Fatima. She and Iqubal were friends. She bravely tells his story, even as her own heart breaks recalling it.

This book is recommended for children ages 8-12. I think this would be a powerful book to be used in either literature circles, or as an interactive read aloud for an older audience of 10-15 years of age.

Charlene Klassen Endrizzi

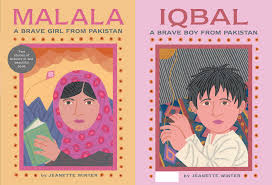

Malala, A Brave Girl from Pakistan/Iqbal, A Brave Boy from Pakistan

Jeanette Winter’s clever format consisting of two biographies in one caught my attention from the start. I was drawn to this picture book based on international attention Malala Yousafzai gained following the Taliban’s attempt on her life two years ago. Iqbal Masih’s story (featured in the second biography) might be frequently overlooked, yet his life parallels Malala’s crusade in many ways. What a courageous, powerful pair of child activists Winter chose for these parallel texts set in Pakistan.

Two years ago my travels to northern Israel, including visits to elementary schools, provided me with a new perspective on the bewildering Middle East conflicts. Subsequent discussions with Grace broadened my lens as she shared expository texts featuring kids like Malala and Iqbal. Their voices express the despair of countless children prevented from attending school in some Middle Eastern countries. Twenty years apart, each of these two brave individuals launched international campaigns demanding education for all Pakistani children. In the 1990s, Iqbal voiced his objections toward the Pakistan’s weaving industry for enslaving children and thereby eliminating educational opportunities. In 2010 Malala denounced the Taliban’s exclusion of girls from school. Heartbreakingly, schools in that country continue to be targets for terrorists. Beginning in 2005, the Pakistani Taliban started destroying hundreds of schools, and recently massacred over 100 children and teachers at an army school in Peshawar.

When I discovered Winter’s Malala/Iqbal picture book, I applauded her efforts to portray terrorist actions for young readers, who need exposure to global children’s rights issues. The publisher recommends this text for children ages four through eight. However, from my teacher’s lens, I see this book as a profound starting point for upper elementary and middle school readers.

Beginning with the book jacket and prologue, Jeanette Winter cautions readers of the dire events facing Malala and Iqbal with words like “brave,” “danger” and “unspeakable violence.” Her simple, direct word choices offer students a vision of two turbulent lives struggling to claim the right to attend school. I understood Winter’s chilling words “unspeakable violence” more deeply upon realizing Osama Bin Laden was killed near Malala’s hometown, Mingora.

Biographies of Malala continue to appear on the book market in light of her various humanitarian awards, most notably her 2014 Nobel Peace Prize. Almost twenty years ago, Iqbal Masih lost his life due to his outspoken criticism of Pakistan’s carpet factory owners. He too received international recognition (Human Rights Youth in Action Award). Two years after Iqbal was assassinated, Listen to Us: The World’s Working Children, came out. Notably, the first illustration in this photo-packed informational text is a large snapshot of a solemn Iqbal, looking squarely at the photographer/reader. Jane Springer deftly analyzes the global dilemma of using children as unskilled laborers, and closes with thoughtful options students can explore to help end this battle. Middle school readers can further investigate Masih’s gripping life story in the chapter book, Iqbal (D’Adamo, 2001).

Grace Klassen

The impact of Iqbal and Malala’s stories on the hearts of my middle school students has been profound. As we began our investigation of issues facing children around our community, country and world, my students generated questions on our Focus Wall such as “Does slavery still exist today? What rights do kids have? Who speaks for the young ones? Why do adults have so much power?”

Our subsequent debates, enlivened by texts such as Winter’s parallel stories of Iqbal and Malala, generated even more personal questions: “What do I stand for? How do I act on what I believe? What is the meaning of courage? How do I find it? What about unexpected consequences?” The depth of conversation was heartening. The simplicity of Winter’s picture book belies the complexity of the underlying global social justice issues. My students’ reflections on their roles in a complex world raised awareness and built empathy, truly grand outcomes of powerful literary encounters.

As a teacher working to create a classroom that honors differences and encourages debate through careful deep reading, I highly recommend Winter’s vivid parallel picture book. It can become a springboard that inspires collaborative projects about young people who have made a difference in our world as they advocate for basic human rights for all children. Better yet, it challenges students to ask themselves, “How can I make a difference?”

Charlene Klassen Endrizzi

Grace, I want to visit your classroom and hear for myself these grand conversations between your Latino and Caucasian students. Questions generated by your 7th graders reflect young citizens’ critical consciousness of their place in our world.

I do not want to overlook Jeanette Winter’s distinct artwork portraying life in Pakistan. I appreciate her rich palate of pink and purple hues, depicting buildings, clothing, even mountains. I wonder how quickly readers of all ages will notice the symbolic kite, hidden in most scenes.

Grace Klassen

Another text I found which layers beautifully with Jeanette Winter’s Malala/Iqbal, was David Parker’s Stolen Dreams, that deepened middle school reader’s understanding of the complexity of children’s rights issues today. A physician from America, Parker uses his camera to capture the dreadful conditions children face in work places around the world. His photographic journey takes us to settings the reader may never visit personally. With his lens, he spotlights enslaved children, thereby opening readers’ minds. His accompanying narrative reveals his compassionate heart, curious intellect, and willingness to name the often-ignored harsh realities. In clear prose, he balances expository text rich with facts and statistics alongside powerful narratives of actual children, whose stories make the heart ache. It is a small wonder that Jose, one of my adolescent students, remarked, “I will never be same after reading this book.”

Teachers wishing to enhance the deep reading experience might use a gallery walk of Parker’s evocative photographs before delving into the text itself. After reflecting briefly on “the hardest work I’ve ever done,” I asked my students to examine each stark photo and consider these questions: “What is this child doing? What conditions do you notice in the environment? How do you think the child feels? How do you know this?” After a period of noticing and frank discussion, groups of children explored the causes and implications that Parker lays out in well organized chapters. They formed presentation groups dedicated to teaching others about their new knowledge. I was not surprised when Parker’s book, Stolen Dreams, was voted the number one High Impact Book of the Year by my middle school readers.

Charlene Klassen Endrizzi

I really like your reader award label, High Impact Book of the Year, on several levels. In working alongside graduate students, I often hear frustrations over the saturated, district-mandated curricula, leaving little room for critical literacy explorations like your Workers and Activists inquiry. Deep reading experiences, a central focus of the Common Core States Standards, regularly occurred in your middle school classroom even before No Child Left Behind requirements. Engaging adolescents in relevant texts like Malala/Iqbal and Stolen Dreams enables teachers to find purpose in their teaching. Your question “How can I make a difference?” challenges both teachers and students to seek new opportunities for using their voice in order to construct their own contribution to our ever-changing society.