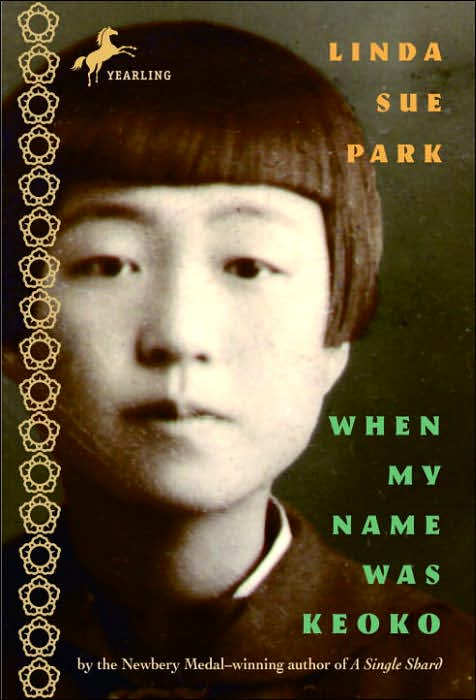

When My Name Was Keoko

Written by Linda Sue Park

Clarion, 2002, 208 pp, ISBN 13: 978-0-168-13335-6

This historical fiction novel focuses on the lives of a brother and sister in Korea during the Japanese occupation in the 1940s. Life is difficult because the Japanese are forcing Korean people to give up their culture, their language, and even their names, to be replaced by all things Japanese. The story is told in the alternating voices of Sun-hee and Tae-yul, who describe the hardships their family faces as Japan becomes immersed in World War II, offering complementary and sometimes differing versions of events. Sun-hee, the obedient daughter, is in the last year of elementary school and loves studying, while her older brother, the favored son, loves speed and machines. Tension mounts as Uncle publishes an underground, anti-Japanese newspaper and Tae-yul takes a drastic step to protect the family. Sun-hee is forced to take on the Japanese name of Keoko, and takes refuge in her writing, worrying that she can only write her Korean thoughts in Japanese; only to have her diary burned by Japanese soldiers. Her father reminds her that they can only burn her paper, not the words or thoughts. Both Sun-hee and Tae-yul develop subtle ways to resist the enemy. Like the Rose of Sharon tree, symbol of Korea, which the family hides in their shed until the country is free, they endure and grow.

This beautifully crafted and moving middle-grade novel of a close-knit, proud Korean family addresses issues of courage, injustice, and determination in the face of oppression. It is an excellent novel for discussing cultural identity because the characters struggle with the obliteration of their culture and language. The structure of the novel in two voices is quite effective in providing two sometimes-opposing points of view and to witness two different paths to resistance. Park provides insights into the complex minds of both characters. The structure also highlights issues of gender as Sun-hee struggles to resist gender restrictions on her participation as a female within the family context.

Linda Sue Park includes an author’s note in which she details her research and the specific historical events and people, including the connections to stories by her parents. She lists additional fiction and nonfiction resources. No issues of cultural accuracy or authenticity have been raised by Korean readers, except in the spelling of Keoko. The actual Japanese spelling is Kyoko, but Park was concerned that the name, which was her mother’s name during the occupation, be pronounced accurately by English-speaking children and so used an alternative spelling. This novel can be read alongside Year of Impossible Good-byes (Choi, 1992), a more harrowing Korean perspective of the same events, and So Far from the Bamboo Grove (Watkins, 1986), a memoir of fleeing as a Japanese child from Korea at the end of WWII. Reading the three books together provides children with an opportunity to see how each author takes a different perspective on the same historical event. So Far from the Bamboo Grove is a controversial book because the author has many historical inaccuracies and negative portrayals of Koreans, but the book provides an important alternative Japanese perspective and accounts of Korean acts of revenge.

Kathy G. Short, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ

WOW Review, Volume I, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/review/i-1/