Making Personal Connections: Conceptual Thinking in Kindergarten

By Kathryn Bolasky, Kindergarten Teacher, Van Horne Elementary School

Being able to connect various pieces of information to a larger concept is a critical skill that students need to make meaning out of what they are learning. Concepts are mental constructs, organizing ideas that categorize a variety of examples or facts (Erickson, 2002). Conceptual thinking about big ideas is typically developed in intermediate grades. This does not mean that young children are not capable of making meaning of what they are learning and thinking about ideas -- it just looks different.

At our elementary school, we have a school-wide focus on using international literature to teach our students about the world through inquiry studies. Students, kindergarten through fifth grade, participate in instructional experiences that challenge them to think critically about different concepts and topics that are important in our world. Our school has a unique learning environment that engages all of our students at their level. Many of these engagements take place in our schools Learning Lab that is conducted by our school’s project specialist, Lisa Thomas. We are also lucky enough to consult with Kathy Short from the University of Arizona. I have had the pleasure of teaching third grade and kindergarten at Van Horne, which has allowed me to experience our research from two distinctly different vantage points.

During my year as a third grade teacher I was amazed by the advanced thinking the students were able to engage in. I remember looking back and being in awe of the way students conceptualized major life issues, like embarking on forced journeys. We had spent time looking at refugee experiences. My students wrote essays synthesizing their thinking (see http://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi2/?page=11). One essay in particular stands out in my mind, written by Andy who had been dealing with his parents divorce throughout the year. He used his personal experience to make sense of the feeling of loss that refugees experience. His thesis statement was, “When you move, you leave things behind.” In his essay he argues, “Life will not fit in a suitcase. When my mom had to move she had to leave pictures of me as a kid. She was really sad because she wanted them. Refugees have to leave their homes, toys, and pets behind.” At eight years old he understand the concept of loss and value of belongings. Moments like these are precious and this year I learned quickly that they are not ones that happen in kindergarten!

While kindergarteners do not typically make conceptual statements like “Life will not fit in a suitcase,” it is important not to underestimate what they can think and say. As I look back at the statements my kindergarteners made, I am pleased and excited to see that they too are able to think conceptually. Each time my class visited the Learning Lab, we read a story aloud, discussed it, and drew about it in some way. Lisa and I took dictation during the drawing engagements to record their thinking. These drawing and dictations allowed me to see a major shift in my kindergarteners thinking over the year. My students started the year by retelling events of the stories and then moved into connecting the stories to their own lives to make meaning of the story.

Figure 1. Graffiti response to Fred Stays with Me! Reyna: This is a picture of the dog taking the socks. Micaela: I think the story is pretty good and I like it. The dog eats the socks.

Retellings

At the beginning of the year, my students were still adjusting to their new school setting. A simple drawing engagement was a way for them to explore not only using markers, but drawing what they thought about the story. Drawings and dictation at the beginning of the year were basic retellings of the stories that were being read aloud. For example the very first time that we went to lab, Lisa read aloud Fred Stays with Me!, by Nancy Coffelt (2007). Our focus was on the power of choice and the decisions students feel they are able to make in their lives. My students discussed this concept on a very surface level. When asked to draw about the story, they created images that were retellings of the story. Reyna responded by drawing a picture of the part in the story when the dog, Fred, is stealing socks. Micaela responded by drawing a similar picture depicting the same part of the story and in her dictation she says, “I think the story is pretty good and I like it. The dog eats socks.” Both Reyna and Micaela responded to an event from the story, but it was not a significant part of the story. They did not make connections to the bigger concept of the power of choice.

Figure 2. Graffiti Board response to I Will Never, Not Ever Eat a Tomato

Making Personal Connections

During our next session in lab the drawing responses started to change from retellings to making self-to-text connections. I was amazed at how fast the shift in thinking was starting to happen. The graffiti board that was created after reading and talking about I Will Never, Not Ever Eat a Tomato, by Lauren Child (2000), contained many responses that made personal connections to the story along with retellings of story events. The students’ personal connections were topical in nature. For example, Sarah drew a picture of a tomato and fish sticks and said, “I like tomatoes. Fish Sticks are yummy.” Sarah connected personal preferences to a minor detail in the story. Although this is not a connection to the story’s main theme about the influence of others on one’s diet, the move from retelling to connections of topics is a significant step in thinking conceptually.

Figure 3. Response to Please Louise.

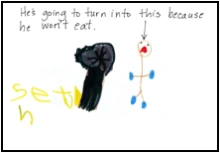

Students continued to make topical connections in the next few sessions of Learning Lab. Seth responded using both a retelling and a personal connection to a topic. He drew a picture of the part of Please Louise! by Frieda Wishinsky and Marie-Louise Gay where the character, Jake, finds the dog and the dog licks his face. Seth drew Jake and the dog and said, “I am drawing a dog jumping on the face because it was funny and I have a dog.” Again Seth connected the fact that there was a dog in the story to the fact that he has a dog at home. This connection is not one that shows Seth understood the main concept of sibling influence, but it does show that Seth was beginning to use his personal experience to make sense of the text. During the same session in Lab, Isaac made a connection that did move into conceptual thinking. After hearing the story, Isaac shared in our discussion that he too has an older brother who is sometimes mean to him. He said, “My brother does not let me battle with him with Pokemon cards.” This comment demonstrated to me that Isaac did understand the big idea of the story because he connected his life to the concept that older siblings have influence over you.

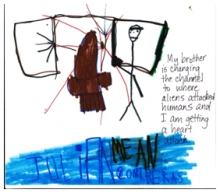

Figure 4. Responses to The Book of Mean People

One particular session in Learning Lab involved a majority of the students making significant gains in their ability to talk about conceptual connections. We were exploring our understandings of power using The Book of Mean People by Toni and Slade Morrison (2002). The students had a lot to say in the discussion that followed the read aloud, making connections from their lives where people were mean to them. For example, Ricky connected the story to a time that his sister was mean to him. He said, “My sister kept changing the channel on the TV when I was watching it.” This connection demonstrates his understanding of the concept that other people and their attitudes and action have power over your life. These connections appeared in their individual responses. This session showed Lisa and I that a majority of the class in fact understood big concepts. While they did not put these big ideas in abstract comments, they evidenced their exploration of these ideas by sharing more conceptual connections that linked to significant themes in the books. We were able to then start planning sessions and engagements that focused on more abstract concepts.

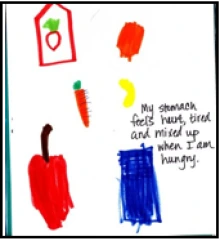

Figure 5. Matthew’s and Seth’s understandings of the concept of hunger.

The most significant example of students’ conceptual thinking came during our investigation into the difference between hunger and hungry as part of our study of the causes of hunger in our world. Students gathered with Lisa on the story floor and were asked, “What are the differences between Hunger and Hungry?” Lisa recorded their thinking on a T-chart. The class came up with clear distinctions based on their personal experiences of being hungry and knowledge they had learned about hunger from previous lab sessions. After we completed the T-chart the class was asked to choose either hunger or being hungry and draw a picture to represent that concept. The responses were throughtful and evidenced conceptual thinking. Ricky used a personal experience to explain being hungry, explaining that his “stomach feels hurt, tired, and mixed up” when he is hungry. Matthew depicted hunger by drawing a picture of a stick figure standing behind an empty table. He dictated that “Hunger means you are starving.” Seth clearly showed his understanding of malnutrition as a result of hunger when he drew a picture of a stick-thin person and said, “He’s going to turn into this because he won’t get food to eat.” The hunger is an abstract concept that not many kindergarteners experience, but many students showed their understanding of hunger by making conceptual comments.

Figure 6. Ricky’s explanation of what it feels like to be hungry.

Strategies That Supported Developing Conceptual Understandings

As I look back over the shift that occurred in my students’ thinking I clearly see that there are two instructional strategies that Lisa and I used to foster their thinking. One of the most important aspects of Learning Lab was creating engagements that built on each other. During our bi-weekly study group meetings, we reviewed the student work and thought carefully about the logical next step for our students’ learning in the lab. By being conscious that our students were engaged in a process, we were careful not to create isolated engagements. This created a context for our students to use in their thinking. They were able to use the information or ideas that they learned from the previous session to help them make sense of what they were currently engaged in learning. We developed instruction from careful assessment of student thinking and learning.

Figure 7. Julian’s Response to The Book of Mean People- a conceptual connection.

Book selection was one of the most important instructional decisions and truly promoted my students’ ability to make personal connections. When I look at the responses that my students created over the year I see a commonality across the most thoughtful ones -- they are all responses to books that the students easily related to. Texts like Please Louise! and I Will Never Not Ever Eat a Tomato gleaned significant responses based on the fact that they deal with sibling interactions, which is easily relatable to my students’ life experiences. I was amazed at the influence that book choice can have on the quality of responses that are produced. As I reviewed my students’ responses chronologically across the year, I was surprised by two sets of responses that were vastly different in significance, yet they happened only a week apart. The first set of responses was from The Book of Mean People where students made strong personal connections to the main themes of the story. I then moved on to look at the following week’s responses and was surprised at the simplicity and lack of connection. I was sure that students would continue the connections they had made the previous week, but I was wrong. Lisa read aloud Clancy the Courageous Cow by Lachie Hume (2006) to discuss the issue of power in relationships and shifting power. My students clearly did not relate to this story based on their responses. The students all responded by creating retellings or making a personal connection to a topic from the story. Not one student made a conceptual connection. I was left confused by the vast difference in the responses.

Figure 8. Responses to Clancy the Courageous Cow. Zachary’s response is a topical response and Isaac’s response is a retelling.

As I compared the two sets of responses, I realized that it was the books that played a significant role in how the students responded. Clancy was a very entertaining read aloud for my class, but not one where they could easily make an immediate connection to their lives. I found the texts that successfully elicited meaningful responses were the ones in which the students could easily find a connection to their own life and that were challenging in content or subject manner. It was imperative that the students relate with the text because it allowed them to make connections to their life in order to make sense out of the ideas we were exploring.

By honoring the notion that kindergarteners can think conceptually, Lisa and I were created learning experiences where students could think about more than just the literary elements of a story during read alouds. My students were able to use their own life experiences to help them make sense of complex issues, like power and hunger. Their statements about these personal connections were not abstract conceptual statements, but evidence of their understandings of large concepts.

References

Child, L. (2000). I will never, not ever eat a tomato. Cambridge, MA: Candlewick.

Coffelt, N. (2007). Fred stays with me! New York: Little, Brown.

Erickson, H. (2002). Concept-based curriculum and instruction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Hume, L. (2007). Clancy the courageous cow. New York: Greenwillow.

Morrison, T. & S. (2002). The book of mean people. New York: Hyperion

Wishinsky, F. (2007). Please Louise! Toronto: Groundwood.

WOW Stories, Volume I, Issue 3 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi3.