Thinking About Thinking with Young Children

By Kathryn Bolasky, Kindergarten Teacher, Van Horne Elementary School

When I moved from teaching third grade to kindergarten, I had to develop a whole new set of expectations for the ways in which young children think about and respond to literature. Now, as I look back over my first year of teaching kindergarten, I am impressed with the progress my students made in their ability to think. Every child walked into my classroom with the innate ability to think and make sense of their world, but they left my room at the end of the year able to think about their thinking and to use literacy to create meaning. When I reflect on how this development occurred, there are several key instructional experiences that supported this shift. Throughout the year I wanted students to engage in reading as a meaning-making process that went beyond learning how to read, the typical focus of kindergarten classrooms. I wanted my students to experience reading as a process of constructing meaning for purposes significant to the reader (Goodman, 1996). In order to accomplish this, I worked to create a literacy rich environment where we learned to read, but also used reading to learn about our world. My students engaged in consistent instructional experiences that allowed them to talk about their thinking and to facilitate their thinking through sketching.

The particular experiences in this vignette occurred in Learning Lab, where I am able to observe and take notes of students’ responses and where I have someone to think with to make sense of their understandings. The Learning Lab is a place of learning and inquiry for us as teachers. We each take our students to the lab once a week for specific instructional engagements and then meet in a teacher study group every other week to analyze student work and think about where we will go next in our inquiry. The Learning Lab is facilitated by Lisa Thomas, our instructional coach, and the work in the lab is determined by our professional learning focus as a school. In this case, we were looking at issues of power through literature.

The first instructional experience with my students was unforgettable -- for the wrong reasons. My students gathered on the story floor and Lisa explained that she was going to read a book and then ask questions. In an attempt to have students explore the concept of power, she read aloud the picture book Fred Stays with Me!, by Nancy Coffelt (2007). My students squirmed, giggled and commented on the illustrations during the read aloud. When Lisa finished the story, we discussed the choices that the character in the story had the power to make and the choices her parents had the power to determine. The students were then posed with the question “Who has the power over your choices at school?” The discussion led to their determination that some choices are made by students and some choices are made for them by others. Lisa supported the discussion by asking questions such as, “Who decides what you do at free choice time?” The students were able to distinguish between a choice they made for themselves and a choice that was made for them.

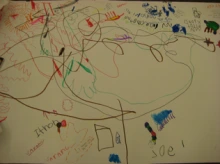

After the discussion, the class responded to the story on a large graffiti board. They moved to a large piece of butcher paper on the floor that had markers scattered in the middle, arranging themselves around the paper. They were asked to draw something from the story. I was elated that at one point all of my students had a marker in their hands and were drawing images on the paper. As the students drew, Lisa and I took dictation from them about what they were thinking. It was not long before markers began to fly and large scribbles appeared on the graffiti board. It was clear that our first instructional experience was coming to an end.

Each week we spent time reading a text, talking about it, and responding through drawing. Although the individual sessions were centered on different ideas about power through the read alouds, the structure of the instructional experiences stayed the same. This was significant because the routine assisted in developing their thinking. Students could anticipate what they were going to be asked to do and so could focus on their thinking instead of the procedures. Dictations changed from “I liked the silly part” to retelling key points in the story. Initially, we were just happy if they stayed with the task and responded to the book instead of wandering off, but gradually we noticed that students were engaging with the story and going beyond retellings or telling what they liked about the story.

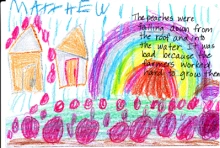

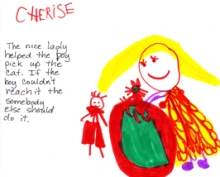

After several months of reading, discussing, and drawing, there was a visible shift in students’ abilities to think about and respond to literature. At the end of March we were exploring the concept of hunger and the power of food. When looking at how weather affects food sources, Lisa read aloud Peach Heaven, by Yangsook Choi (2005) in which farmers lose their crop when a huge rain brings peaches down the mountain to the town below where children eagerly eat the expensive treat. After the read aloud we had a discussion and I remember thinking for the first time that we had moved past discussing what they liked about the story into thinking about the important events from the story. I was excited to see this change. The sketches that the students produced were also beginning to reflect their thinking about the stories we were reading.

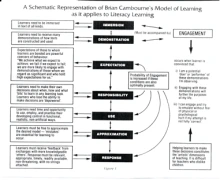

As I reflected on these changes in my students as thinkers, I found that Brian Cambourne’s Model of Learning (1988) was useful in understanding why these experiences were valuable. Cambourne’s model identifies the natural environmental factors that contribute to a learner’s success in attaining oral literacy and how these might be applied to written literacy. In my classroom these environmental factors were present in our quest to develop the ability to think about our thinking, particularly in response to literature. In the model there are eight concepts or conditions that are imperative for the learner’s development: Immersion, Demonstration, Engagement, Expectation, Responsibility, Use, Approximation, and Response. These eight factors helped me explore the academic experiences of my students and consider their role in helping students begin to think about their thinking. Cambourne (1988) represents his model in this diagram:

Immersion, Demonstration, and Engagement

Exposure to new learning experiences is a constant factor in kindergarten. As Lisa and I created new learning experiences for students, it was clear that immersion, demonstration, and engagement were vital components that needed to be addressed to assure success. When trying to develop student thinking, immersion does involve flooding them with books but must also include access to engagements that challenge students to think and respond. Susan Kempton (2007) argues that “Kindergarteners, especially early in the year, can understand much more complex texts than they can read” (p.104). To honor that notion my students were immersed in experiences to develop their thinking from the very beginning of the year. I wanted them to have a full picture of school as a place to push their thinking.

Often kindergarten teachers believe that they should start with simple routines and expectations and hold off reading complex books and asking students to respond and talk about books until much later in the year. Each week Lisa and I set aside time to read a selected book and gave my class a chance to interact with the text. We started this from the beginning of the year and did not wait until they were older because I wanted my students to become accustomed to the expectation that they are thinkers. Even if their initial responses were a few retellings and “I like” statements, we were creating the expectation of thinking and talking about literature.

Careful consideration went into selecting a text to read aloud to students. A key aspect of immersion is to create quality experiences that expand their life experiences. My students came with a wealth of knowledge and I wanted to give them the chance to use what they already knew in order to gain more insight about their world. One way that we accomplished this was by creating sustained immersion experiences. Lisa would read a text with a complex issue and then give students the chance to talk about the book. After the discussion, students responded on paper using sketching to continue their thinking about the story. Students were involved with a single text for close to fifty minutes during these instructional experiences. That is a major feat with five-year-olds, especially my class of 17 boys and seven girls.

Spending time every week on these experiences not only gave students the opportunity to be immersed in literature-rich experiences, but the time spent also served as a demonstration of the thinking process. This demonstration came in many forms. According to Cambourne (1988), demonstrations can be “actions or they can be artifacts” (p. 34). The first demonstration the students experienced was the teacher language and dialogue that was facilitating their talk. Lisa and I did not speak to or treat my students like they were little kids; instead we referred to them as thinkers. We shared our thinking about a story as a demonstration for them, but were careful not to lead them to believe that our thinking was what they should be thinking. We diligently fostered an open dialogue that accepted all thoughts so students felt safe to share their ideas without fear of judgment.

Immersion and demonstrations are only successful if the students are actively engaged in what they are doing. Cambourne (1988) argues that while learners are subjected to thousands of demonstrations, “a high proportion of these demonstrations merely wash over them and are ignored” (p. 34). To keep the students engaged, time spent during these literacy experiences was completely focused on the students and their thinking. Apart from the read aloud, the experiences were student driven. Students voiced their opinions and connections during discussions and recorded and developed their thinking in artistic responses. Of the 50 minutes that we spent in these experiences, 35 of them were devoted to active participation by students. The experiences were structured to give ample time for them to talk and explain their thinking. It was important for students to discover their thoughts and not for Lisa or I to lead them where we wanted them to think.

Expectation and Responsibility

The high level of engagement that my class exhibited during these experiences was closely related to the expectations I had for my students. Brian Cambourne (1988) explains that “expectations are subtle and powerful coercers of behavior” and that through these expectations “young learners receive clear indications that they are expected to learn … and that they are capable of doing it” (p. 35). Simply setting aside time in our week to engage in literature experiences was a significant aspect of developing the expectations I had for my students, and a strong signal that I valued this thinking time. I demonstrated to my students that what we were doing was important enough to spend a significant amount of time doing it week after week. Each time my class engaged in a literature experience, they understood that what they were being asked to do was meaningful and, more significantly, attainable. By routinely engaging in literature experiences, my students were able to build a sense of confidence about their abilities as thinkers. During these experiences, my students knew that they were going to be responsible to share their thoughts, and knowing they had something to share validated their thoughts.

Use

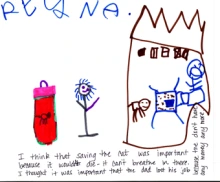

These weekly experiences also gave students ample time to use their thinking. Cambourne (1988) argues that “learners need time and opportunity to use, employ, and practice their developing control in functional, realistic, non-artificial ways” (p. 33). Each week students had the opportunity to hear a text and engage in meaningful response strategies that enabled them to make meaning. One response strategy that was particularly effective for my students was graffiti boards. This response strategy is a flexible and so was easily adjustable to fit the needs of my students. At the beginning of the year Lisa and I had my class respond together on a large piece of butcher paper on the floor. By having a single board we were able to keep them in close proximity as they explored using markers to record and facilitate their thinking about a story through sketches, words, and dictation. As the year progressed the graffiti boards changed from being one large piece of paper to small group boards and eventually to individual pieces of paper. As my students started to gain ownership of their thinking it was important to support them by giving them more individualized way to respond.

In January, students responded to Tight Times (Hazen, 1983), a picture book about a young boy who is not allowed to have a dog because times are tight, but who brings home a starving kitten he finds in a trash can on the same day that his father loses his job.

Approximation and Response

Graffiti boards were successful throughout the year not only because they were flexible response strategies, but because there was not a targeted answer. From the beginning of the year Lisa and I accepted any response the students gave as meaningful. Of course the responses that were given at the beginning of the year were simple when compared to the more complex responses at the end of the year, but that was to be expected. Lisa and I made it a point from the beginning of the year to value students’ understandings and resisted the desire to talk them into a thought.

Lisa and I wanted to understand the ideas we were exploring in literature through their eyes. We achieved this by accepting and celebrating their work and ideas, even at the first when their responses were short statements and retellings and it would have been easy to be discouraged. Their early responses were approximations of responses to literature, but we responded to them as meaning-makers who were working to make sense of text. Cambourne (1988) discusses approximation as related to children who are learning how to speak, stating that “there is no expectation that fully developed ‘correct’ (fully conventional) adult forms will be produced. He points out that adults expect baby talk from young children and it is “warmly received and treated as legitimate, relevant, and meaningful” (p. 37). The students’ responses on the initial graffiti board were, of course, raw and simplistic, but they were still representations of their thinking. It was important initially to accept these responses as they were in order to promote their confidence for the next time they were asked to respond. By validating their thinking, I sent my students a strong clear message that they were thinkers and they had the skills to engage and be successful in these literacy experiences. This was the most important teacher response I could have given.

Conclusion

Looking back on the school year through the frame of Cambourne’s work, my actions as a kindergarten teacher seem purposeful and effective. At the time, however, Lisa and I were both struggling and often questioned ourselves on how to most effectively invite students to respond to literature and to be aware of themselves as thinkers. What we did not want to do was to give up or wait until later to signal that we expected them to engage meaningfully in our work around literature. Out of desperation, we developed a routine of read alouds followed by talk and response and kept that routine, no matter how discouraged we were after a particular session. I realize now that it was this consistency of engagement and expectation of thoughtfulness that created an effective learning context for all of us.

References

Cambourne, B. (1988). The whole story. Auckland: Ashton Scholastic.

Choi, Y. (2005). Peach heaven. New York: Farrar, Straus, & Giroux.

Coffelt, N. (2007). Fred stays with me! New York: Little, Brown.

Goodman, K. (1996). On reading. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Hazen, B. (1983). Tight times. Ill. Trina Schart Hyman. New York: Puffin.

Kempton, S. (2007). The literate kindergarten. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

WOW Stories, Volume I, Issue 3 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi3.