Challenging Stereotypes of Poverty through Children’s Literature

By Kaye Wingfield, Fourth/Fifth Grade Teacher, Van Horne Elementary School

Many children accept society’s stereotypes of the poor as dirty, dishonest, lazy, and dependent on free handouts from hardworking citizens. These stereotypes are so pervasive that children cling to them even when presented with contradictory evidence, and even when their own families could be viewed as poor. The sociopolitical issue of poverty and economic difficulty was particularly relevant and poignant in Spring 2009 when many families in our school experienced changes in their lifestyles due to the economic crisis in the United States. Children from a range of backgrounds, including middle class and working class families, were struggling and experiencing “tight times,” not just the families previously viewed as “poor.” Our students saw their own parents, friends, and family members struggling with financial difficulties or heard news reports about people in Tucson who were losing their jobs and worrying about their homes and feeding their families. They had previously assumed these events only happened in faraway places, not in their own families and community. We realized that this context provided an opportunity to challenge students to push their thinking and critique some of the common stereotypes associated with people living in poverty.

We wanted children to realize that many people, including themselves, experience “tight times” and difficult situations, despite working hard and often due to no fault of their own. They needed to see themselves as connected to the conditions that can lead a family to experience poverty, instead of viewing the “poor” as somehow different and inferior. At the same time, the tight times experienced by families do vary greatly, and might mean anything from delaying a trip to Disneyland or the purchase of a new toy to not having enough to eat or a place to sleep. We wanted children to recognize the significant differences between delaying “wants” and not meeting basic “needs.”

We had explored conceptual issues of power during the fall semester, and had begun talking about the power of diet and food within our school. Lisa Thomas, our Learning Lab instructor, connected to these ideas as a way to move into a discussion of tight times. Lisa reminded students of a previous activity where they documented what they would eat if they had the power to choose anything they wanted versus if their parents had the power to force them to eat only the things that they thought were good for kids. This activity included a discussion of power and diet in our world and in our lives. She also reminded students about the canned food drive at the school before the Winter Holiday. Students talked about the times in people’s lives when things are tight and how tight times can lead to situations where there is not enough food or families can not buy extra food or go out to restaurants.

Lisa read aloud a book about what causes tight times in one particular family. Tight Times (Hazan, 1979) is a story about a young boy who desperately wants a dog, but his father says no because of tight times. Examples of tight times in the book include eating generic cereal because of rising prices on name brands, playing in the sprinkler in the yard instead of going to the lake, eating lima bean soup rather than roast beef, and coming home from school to a babysitter because the mother needs to work. One day, the father comes home early because he has lost his job. When the boy goes outside while his parents talk, he hears a cat crying in trashcan. He brings the cat home, getting it milk with the hope that his parents will agree to let him keep the cat. His plea brings tears for the whole family. The father agrees to keep the cat as long as the boy promises not to ask about a dog again. In reply, the boy decides to name the cat Dog.

Lisa encouraged the students to talk about the book while she and I took notes about their comments. The students were aware that they did not have to raise their hands to speak during discussions, but they needed to wait for the person before them to finish. We had also been working with them on listening to and acknowledging previous comments.

Kaitlynn wondered why everyone in the family cried when they saw the cat drinking the milk. Zachary responded that they cried because the cat would be one more stressor and they would have to worry about having money to buy cat food. Abbey commented that they may not have been crying about the cat specifically but about the dad losing his job. Some students were interested in trying to figure out why the dad lost his job. Several wondered whether the tight times might not just be affecting this family but others as well. Maybe the company had to lay off lots of their employees like all the people at the Tucson city newspaper who were losing their jobs at that time. Also the babysitter in the book lost her job because the dad would now be home. A number of children were concerned about why someone would put the cat in the trash can. One child wondered whether the cat got in the trash can because it was looking for food. Lisa asked why the dad changed his mind about getting a pet and let the boy keep the cat. Logan and Jacob thought that maybe he thought the cat was little and needed help or wanted the kid to stop asking for a dog or cat.

After this discussion, each student created a sketch to stretch on the most significant meaning of this story. The students were asked to go to a table and work silently, independently, and focus on listening to their brain. Instead of talking, they were to think and then draw, using visual images and symbols to express their ideas, rather than sentences. Words could be used as labels for these visual images, but they were primarily to use visual images to reflect on the meanings of the story. Their stretches reflected common threads of issues, such as the father losing his job, the family having little money, and connections to pets. Adrianna’s sketch went further with her words and symbolism focusing on emotions, such as stress and depression. Sean used the symbol of a rainbow going from bright colors and happiness to more somber colors and tears of sadness.

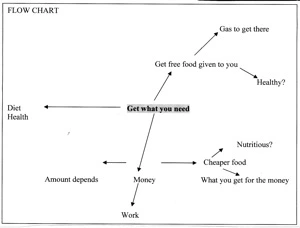

After completing their sketches, the students returned to the whole group and created a flow chart of their thinking about the possible consequences of tight times for food/diet and health.

During the discussion about getting free food, Frank said his family had been to the Community Food Bank to get a food box because his mom’s hours had been cut at work and there just wasn’t enough money for food. He was worried about his mother having enough to eat. Sometimes students associate laziness and the expectation of handouts with people who are poor. There is also a disconnect between people that students perceive as poor and themselves. Frank’s comment indicated that students were becoming comfortable with sharing their experiences and not being ostracized by the group because of an economic situation. His comment helped other students realize that there were classmates in their midst who were experiencing what they thought was happening elsewhere. Through personal experience, books, news reports and class discussions, students seemed to be moving away from some of the more common stereotypes and were beginning to understand that everyone experiences these tight times to some extent.

During Learning Lab the following week, students were encouraged to think about the differences between needs and wants and consider how the consequences of tight times can differ from family to family in significant ways. Lisa had the students review a book they had previously discussed, The Lady in the Box (McGovern, 1997) which Kygatheo summarized as a story about a homeless lady who needed shelter, food, and blankets. Lisa also asked them to revisit Tight Times, which Terrell summarized as a book about a boy who had to do without a pet he wanted. Terrell pointed out that the boy had food, just not the kind he wanted. Lisa reminded the class that we had been discussing food and the issues of tight times and that we wanted to think more about these issues, in particular by talking about how tight times can mean different things to families, including doing without, waiting and/or getting help from others.

Mary Cowhey (2006), author of Black Ants and Buddhists, finds it powerful to draw on personal experiences or experiences that are public knowledge when talking with students. Consequently, Lisa talked about a current news report in the United States about the executives who run the car companies and make millions. They were asking for tax dollars to help their plants stay open because they were in trouble, but then got in private jets and flew to Washington to meet with Congress to ask for that money. People in the country were upset and wondered whether the government should spend money to help these companies. The next time the auto executives had to go to Washington, they drove in cars, showing that even they were being affected by the economy, however, the debate continued about whether they really needed the help.

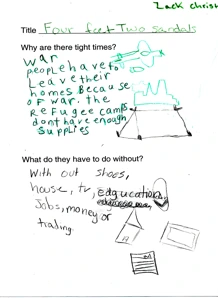

Lisa asked the students to work with a partner to read a book and think about the causes of tight times. The characters in the books make decisions about what they need and what they want and students were to infer the causes of the tight times and think about what the characters were doing without or had to wait for as well as whether that was a need or a want. Lisa asked the students to fill out a sheet answering two questions: Why are there tight times? and What do they have to do without? Students were to consider different possibilities and think about who struggles more in tight times, people with needs or people with wants.

Each partner chose one book to read together from a text set that included: Beatrice’s Goat, Fly Away Home, A Shelter in Our Car, A Castle on Viola Street, Peppe the Lamplighter, Those Shoes, The Hard Times Jar, Bothers in Hope, A Chair for My Mother, If the Shoe Fits, Homeless, and Four Feet, Two Sandals. They read together and then talked through and wrote their responses to the questions.

Students noted a range of reasons for why people experience tight times:

- War leads to lack of food (leave their homes/refugee camps may not have enough food)

- Losing jobs (not enough money for medicine/food/shelter)

- Sickness (parents sick/can’t work/no money for food or shelter)

- Both parents working but jobs don’t pay enough to cover food/shelter/clothing

- Too many bills to pay

- Business not selling enough merchandise so can’t afford much food or clothing

- Can’t replace things that break

Students also noted a range of things that people do without in tight times:

- Shoes and clothes

- House/Large enough house to fit large family/Repairs in a house

- Money

- Education

- Car

- Books

- Pets

- Friends

- Family

After reading the books and recording their thoughts, students returned to the whole group and shared a short summary of each book and talked about the needs and wants evident in the books. During the discussion, Max shared that he was saving for some Bionicle toys and instead gave his money to his mom because they had run short on food for the week. The students did not directly comment on what he said, but in looking around the room, it was evident that this gesture tied directly into what they were reading and made it relevant to their lives.

Finally the group worked through where to place the books on a continuum between doing without needs and doing without wants. For each book, they had to decide where it would go on this continuum between needs and wants in relation to the other books, requiring some difficult and complex thinking and distinctions. They clearly understood that doing without food and shelter was definitely a need and doing without a new or popular pair of tennis shoes was a want, but placing books in the center of the continuum involved a great deal of discussion and negotiation. They agreed to put the family where the mom still worked and the dad had lost his job in the same spot as the family where both parents were working but did not make enough money to support the family with the appropriate housing and food. They put books where both parents were working but not making enough money to meet the family needs slightly to the right on the continuum towards doing without wants. To the left on the continuum, they put books where the parents were not able to work due to war, illness, and job loss as well as books where children did not have parents to support them.

The students did not blame the victims in these circumstances and didn’t fall back on stereotypical judgments that sometimes are connected to these situations. For example, when they encountered a family that was doing without things, they didn’t write or say, why don’t these parents get a job? If there wasn’t enough money to support the family, they didn’t say, why did they have so many children? or why did they spend their money on this item instead of that item? They seemed to grasp the concept that these issues are deeper than just the individual family unit and that these situations happen for many reasons around the globe. This discussion reflected a major conceptual shift in their thinking and recognition of complexity in the functioning of societal systems.

The students continued to make connections about the concept of needs and wants throughout the rest of the semester. One such time involved a discussion that followed our Global Feast, a school-wide simulation of food distribution and hunger around the world. Each group of students represented a percentage of the world and reflected how food is distributed –- those who have more than their fair share of food, those who have just enough to eat, and those who never get enough food to stay healthy. The food they received ranged from an abundance of pizza to just enough beans and rice for each small group to one small bowl of rice for a whole group. The students who had just enough beans and rice for their small group to eat realized that they wanted pizza, but it wasn’t a necessity. They could survive on their portions, while the large group that had only one small bowl actually needed more to survive.

Another situation involved the Scholastic Book Fair that occurs twice a year at school. Students usually rush in during the preview time and list all sorts of books, toys, and posters that they want to buy. During the spring, I noticed a few students looking at the toys and the posters and telling each other that, with money being an issue for their family, they were going to spend some of their own money and ask their parents for less. They were going to limit themselves to one book and one poster, even though they wanted more than that. Some even commented that they didn’t need any of the merchandise. Nate said he needed to get a book for his book report and Colton replied that he could actually get a book from the library. Jeremiah commented that the PTO needed the students to buy books to help with their fundraising.

These comments and distinctions between needs and wants indicated that students had taken on a new awareness about needs and wants as part of their thinking and actions. By starting with personal connections to tight times, students were able to look at their everyday lives and community from a new perspective and not just locate economic struggles as a problem that was “out there” away from their own immediate worlds. Literature provided a safe way for them to make these connections without revealing too much about their own family situations, unless they chose to do so. Literature also provided a way to look at multiple family contexts and societal situations that might cause difficulty, so that they did not reduce tight times to a narrow view of the causes and consequences. Through the literature, they came to recognize the complexity of these causes and the range of possible consequences, as well as to develop empathy for those who struggle with tremendous needs, not just wants. These understandings of causes and consequences, in turn, provided students with ways of thoughtfully taking action. Instead of holding onto stereotypes, they took an important step away from blame and charity to considering how to make a difference in the world.

References

Bartone, E. (1993). Peppe the lamplighter. Ill. T. Lewin. New York: HarperCollins.

Boelts, M. (2007). Those shoes. Illus. N. Jones. New York: Walker.

Bunting, E. (1991). Fly away home. Ill. R. Himler. New York: Clarion.

Cowhey, M. (2006). Black ants and Buddhists: Thinking critically and teaching differently in the primary grades. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

DiSalvo, D. (2001). A castle on Viola Street. New York: HarperCollins.

Gunning, M. (2004). A shelter in our car. Ill. E. Pedlar. San Francisco: Children’s Book Press.

Hazen, B. (1979). Tight times. Ill. T. Hyman. New York: Viking.

McBrier, P. (2001). Beatrice’s goat. Ill. L. Lohstoeter. New York: Atheneum.

McGovern, A. (2007). The lady in the box. Ill. M. Backer. New York: Turtle.

Smothers, E. (2003). The hard-times jar. Ill. J. Holyfield. New York: Farrar, Straus, & Giroux.

Soto, G. (2002). If the shoe fits. Ill. T. Widener. New York: Putnam.

Williams, K. & Mohammed, K. (2007). Four feet, two sandals. Ill. D. Chayka. New York: Erdmans.

Williams, M. (2005). Brothers in hope: The story of the Lost Boys of Sudan. Ill. G. Christie. New York: Lee & Low.

Williams, V. (1984). A chair for my mother. New York: Greenwillow.

Wolf, B. (1995). Homeless. New York: Scholastic.

WOW Stories, Volume I, Issue 3 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi3.