Creating Conceptual Understandings of Hunger

By Kathryn Tompkins, Third/Fourth Grade Teacher, Van Horne Elementary School

Most of the students in our small public school seem to be well-taken care of. They know that they have a roof over their heads, clothes to wear, food on the table and lots of love. So when our parent organization decided to sponsor a canned food drive, we wondered whether the students really understood what it is like to suffer from hunger -- not to be hungry but to know hunger.

As the holiday season approached, students collected canned goods for the food drive. In a class discussion, we talked about “tight times” and why families might need extra food. The students kept referring to the “economy” as the reason that people were going through tight times, but didn’t really know what the economy entailed. They were repeating words they had heard from the adults around them without a deep understanding of those ideas. The class did decide that they wanted to collect good food from home, not food that was out of date or that they wouldn’t want to eat themselves, and donate the food to families in need from our school, giving the remainder to the community food bank. Students brought food to donate and placed it on a large table in the hallway that was organized by proteins, grains/rice, and fruits and vegetables. The students were also aware that the student council was selling popcorn each Friday and the proceeds would go to buy additional food for hungry families.

School-wide, students collected a large amount of food. They were proud of their accomplishments but teachers couldn’t help but wonder if students understood the magnitude of the need for food, including people in their own community. To most students, hungry people are the guys who stand on the street corners holding up signs or people who live in other countries that they see on television. Hunger was not an issue that they felt was prevalent in their city or neighborhoods. As teachers, we were uncomfortable with students’ misconceptions about hunger and their lack of understanding about the global and local issues involved with hunger.

When we returned from our winter break we decided to focus on hunger to build stronger conceptual understandings of hunger as a global and local issue. We began by talking about diet, since it was January and there were constant television commericals and newspaper ads about diets. Many students thought diet was a plan to lose weight, but Elizabeth said, “What you eat is your diet. Diet also tells what animals eat. Bird has a diet of berries and bugs.” Evan simply said, “Good food or bad food is your diet.”

We also talked about whether children have power over their diets. We read aloud Burger Boy (Durant, 2005) about a boy who only eats burgers until he eventually turns into a burger and is chased by hungry animals and people. He then eats vegetables to turn back into a boy and his mom warns him that he is going to turn into a carrot -- and he does. This book led to discussions about the need for a balanced diet. Mason said that you need to “eat a little bit of everything.”

To think more about power of choice related to diet, the students were given a paper with two large circles. On one circle, students were asked to put all of the foods they would eat if they had the power over their diet, and to put what they would eat if their parents had all of the power in other circle.

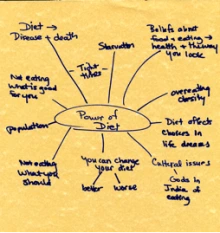

We then came back together as a class and created a web showing student thinking about the power of diet. The class decided that if we don’t eat what we need, then we face obesity, starvation, or disease. We have to change our diets. The students seemed to be seeing some of the larger issues and not just focusing on food as what they put into their mouths.

The next read aloud was Tight Times (Hazen, 1979) about a family whose father loses his job and, even though mom is still working, they can’t afford what they need. Kylie worried about the family because, “If they can’t afford vegetables, then they can’t eat healthy and they will have a low immune system.” Tayler didn’t understand why they didn’t have money if they had jobs. Each student created a Sketch to Stretch to show the symbolic meaning of the story through visual images and labels. Many created sketches that included a variation of NO $= NO FOOD.

Evan said, “I drew a no money sign equals unhappy because they are sad and don’t have food or pets.” Edel commented, “In the first picture the person has enough money to buy food for their family. In the second picture, they don’t have enough money to buy food. The food is less and the bowls are smaller and they’re having very tough times right now.”

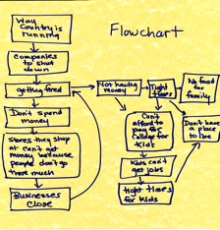

In large group, students created a flow chart to show the consequences of tight times. The flow chart traced the way problems in a country can lead to companies closing and people losing jobs and so not having money for an education and not being able to get a good job, eventually leading to people ending up homeless and without food.

What seemed hardest for the students to understand was the idea that children could suffer from hunger in a home where there were two working adults. They couldn’t figure out how people could have jobs and still be hungry.

We contacted the community food bank and a representative was able to come out and do a presentation that included informing the students that most food bank recipients do have jobs -- they just don’t make enough money to take care of themselves. The representative told the students that the other two major groups of people who need food in Tucson are children and senior citizens. The picture of the homeless man in ragged clothes at the stoplight or the child in India seemed to be fading.

A turning point came when students worked in small groups to read sections of Famine: The World Reacts (Bennett, 1998) and focused on the differences between hunger and feeling hungry. The information they received from this book helped them understand the difference between rumblings in your stomach and going day after day without enough food to ever satisfy hunger and so always feeling sick, weak, and tired. They also began to understand the difference between chronic hunger where a person has just enough food to stay alive over a long period of time before eventually dying from disease and famine where there is suddenly no food and starvation often leads to a quick death.

Then we held a global banquet with all of the classes from the school. As the students entered the library, they drew a red, yellow, or blue card. Those with red cards sat together on the floor and represented 25% of the world’s population who are experiencing chronic hunger. They only received a tiny amount of rice to share. Those with yellow cards represented 60% of the world who get just enough to eat. They sat at small tables and shared rice and beans with enough for everyone to get a good portion. Those with blue cards represented the 15% of the world who get more than their share. They sat at fancy tables and had tons more pizza than they could possibly eat. During the banquet some students “lost their jobs” and had to switch toanother group and one student doubled her income and got double her share of pizza. The experience demonstrated to the students that there is plenty of food in the world to feed everyone, but that it isn’t distributed properly.

After the banquet we returned to our room to discuss what happened. I tried to get the students to think about what the banquet represented by asking “why?” to their complaints about not being in the blue group. After much discussion, they decided that location plays a huge part in food availability. They realized that they were fortunate to be born in a location where so many foods are available. They also felt that parents’ jobs and incomes make a big difference in what kind of “hunger situation” kids face. Evan seemed to sum up our thinking when he said that, in the real world, people don’t share their abundances and so others face horrible hunger. Engaging in this drama experience helped students understand that hunger is often the result of factors over which people have no control and to feel frustration over being in the wrong place and so not getting the food they needed or wanted.

Our explorations of hunger continued through read alouds, such as the novel Nory Ryan’s Song (Giff, 2000), the story of a young girl’s experience of hunger in the Irish Potato Famine, along with picture books that provided a range of perspectives. These books put a human face on the misery that accompanies hunger so that the students would see hunger as more than numbers.

The students decided that they needed to take action to help those suffering from hunger, in particualr they wanted to help a country in Africa. We did some research on various Web sites, and students wanted to focus on raising money for food and water for refugee camps. They practiced learning the different countries in Africa and the states in the United States. Then they asked family members to sponsor them for our “map-a-thon” and they studied the maps each night! After the test and the donations had been collected we had raised almost $300. The students had worked on their own to raise money to help fight hunger. The most valuable lesson they learned was that children can make a difference and take action. They just had to come together to work for the cause.

Through these many experiences, the students began to develop a conceptual understanding of hunger and of the causes and prevalence of hunger in the world and in their community. Most adults, when asked to define hunger, would refer to the charitable organizations that ask for sponsors of starving children across the world. They would say that hunger is an issue faced by other countries, particularly in times of drought. It’s not a surprise, then, that our students have these same misconceptions. Hunger is right in their neighborhoods as well as a real problem all over the world. We may have enough food available to feed the world’s population, but without a more complex awareness of hunger and its causes, nothing will change. As teachers, we need to develop deep conceptual understandings of global and local issues like hunger or we risk maintaining the status quo -- feeling pity for those who are in need without any sense of responsibility for understanding that need or taking action for social change.

References

Bennett, P. (1998). Famine: The world reacts. Mankato, MN: Smart Apple.

Durant, A. (2005). Burger Boy. Ill. M. Matsuoka. New York: Clarion.

Giff, P.R. (2000). Nory Ryan’s song. New York: Scholastic.

Hazen, B. (1983). Tight times. Ill. T. Hyman. New York: Puffin.

WOW Stories, Volume I, Issue 3 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi3.