Understanding by Looking Below the Surface

By Kathryn Tompkins, Third/Fourth Grade Teacher, Van Horne Elementary School

By my eighth year of teaching elementary school, I assumed that I had pretty much figured out children by the end of the first day of school. With Elise, I learned how wrong my initial impressions could be. Elise not only taught me the importance of carefully observing a child in multiple contexts, but also the significance of curriculum that really engages children as thinkers. I think we often underestimate children, particularly children who are quiet or unpredictable in their responses. This experience forced me to be a “kidwatcher” as I got to know Elise in as many contexts as possible and came to see her as a unique and valued person (Goodman, 1978).

Elise started out as quiet, almost withdrawn. She was the type of child who disappeared in a large group of students, especially my classroom which was dominated by a group of boys who were highly verbal and loved to hear themselves talk, whether or not they had anything to contribute. She was probably also somewhat intimidated by the fact that she was a third grader in a third/fourth combination classroom and so younger than many other students. Elise was not a typical quiet child, because she would fly off the handle at things that seemed minor -- someone knocking her paper off her desk or brushing by her too closely. She would yell and dissolve into tears, asking to be left alone. It was almost as if she allowed her resentment to build up inside like a pressure valve that would suddenly blow over something relatively minor. I was worried how I would work with this young lady for nine months.

When we started to look at the world through literature, a different side of Elise began to emerge. I recognized a sense of compassion like none I had ever seen in a child. Elise sees the bigger picture in life. I would describe her as someone who “gets it” in the sense that she understands how the world works and the larger social issues that influence our actions and thinking. She thinks about the “why” behind actions, not just what is happening and that’s unusual at this age level. As sensitive and bright as she was, she still held back in class discussions. She would make one or two comments that would blow me away, but never monopolized a discussion with her thoughts. Her connections were always to the bigger issues in a story, not the details, and she often took a stance that was in opposition to the popular view being expressed by other class members.

For example, after listening to Tight Times (Hazen, 1983), about a family where the father loses his job and tells his son that they cannot afford a pet, many children focused on the cat the boy found in a garbage can or the family’s lack of money in their sketch to stretch responses. Elise’s sketch highlighted the economic system and how the closure of stores affects people in losing their jobs and therefore not having enough money for food. She also noted that while people can lose their jobs, animals never do.

Even in relatively straightforward projects, Elise’s thinking stood out. When class members drew two plates with their choices of food on one plate and what their parents would choose for them on the other plate, most drew hamburgers, pizzas, sodas, and ice cream. Elise’s plate held broccoli, dim sum, mango nectarine. Horchata popsicles, and yogurt.

I began to see her as a child who was constantly engaged in deep, complex thinking and who could see the underlying interconnections between events and people. She thought about how people thought and why they took particular actions, but she had also learned, for a range of reasons, to only occasionally share that thinking with others. Elise seemed to think and feel deeply but to suppress much of those feelings and thoughts within her, only occasionally letting them emerge; the problem was they did not always emerge in socially appropriate ways. She was often overlooked by other children in the classroom because she so rarely took initiative. All of that changed at our global banquet.

For our school’s global banquet we decided to have the students separate into three different groups to represent the world’s population. There was the very small blue group that represented the wealthy. They each received a large pizza to eat. The largest group was the yellow group and they had bowls of rice and beans. The red group represented the 25% of the population in the world that never gets enough to eat. They had one small bowl of rice to share among 25 children.

Elise was a member of the red group. The red group, consisting of first through fifth graders, sat on the floor in a circle around a tarp. They watched as the other two groups got their food, eagerly awaiting their portion. When the small bowl of rice was set in the middle of their circle, they were very disappointed. Several of the older students edged their way to the outside of the group, staring longingly at the pizza being devoured by the blue group.

One of the dominant fourth grade boys from my classroom grabbed the bowl for himself and another friend, turning their backs on the group and stuffing the rice in their mouths. Most of the students just stared in shock. They weren’t about to say anything, but. Elise wasn’t like most students. With her emotions raging, Elise jumped up, grabbed the bowl out of his hands and carefully began passing the rice out to each member of her group, making sure that each got a handful. She stood up for what she thought was right, is a rarity among elementary-school aged girls.

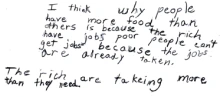

At the end of the banquet, the students were asked to each write a reflection before leaving to go back to their classrooms. Elise’s reflection indicated her understanding of the interdependence among different groups of people and the problem of the “haves” getting more and more so that the “have nots” continue to get less and less.

Back in the classroom, we talked about what students would like to do to help fight hunger. Elise said that it was important to take action because “it helps people in need and makes the world a better place.” She also thought it was important to learn and tell people about it in order to “form a group” to work together.

At the end of the school year, the students each created a sketch to stretch using visual symbols to show the meaning of taking action. Elise told us that her sketch focused on the need to help the hungry and that everyone in the world, whether from the yellow, blue or red group, has to help. The light bulb signified the need to know about hunger and what causes hunger to figure out how to help others, and the heart signified that people have to want to do it by caring and making a choice to help. This sketch reflected her understanding of the complexity of the issues involved in taking action on the global problem of hunger. Her understandings of the need to connect the heart and mind and to hold everyone responsible for action are impressive, especially given that she was only nine years old at the time. Elise sees the bigger picture in life and wants to work with others to make positive changes in the world.

What I found interesting was that this experience seemed to help Elise find her voice in the classroom. I noticed that she spoke up more frequently in whole class meetings and was more likely to express her perspective. She was willing to publicly take unpopular positions in discussions and to explain her thinking. When the dominant boys tried to override her voice, she asserted herself to make sure her perspective was heard. Taking such a public stand against greed and inequity in the global feast seemed to have given her a sense of personal empowerment and she continued to act on her own sense of power. The tears and outbursts almost completely disappeared as she expressed her thinking rather than holding it inside her.

I believe that our classroom learning environment played a key role in supporting Elise in developing this sense of empowerment. In a more traditional setting, I think she would have remained silenced, keeping her thoughts and feelings inside. Elise flourished in a classroom where her thinking was challenged and where she could engage with critical and complex issues about the world. Another essential aspect of this environment was that we valued multiple perspectives, never settling for one “right” answer or response. We always for a range of perspectives on any issue or piece of literature and this supported Elise in being willing to make her ideas public. We were inquirers, more focused on creating new understandings and asking new questions about complex issues, than on finding a simple answer. In more than one way, Elise taught me to look below the surface -- of both children and ideas.

References

Goodman, Y. (1978). Kidwatching: An alternative to testing. Journal of National Elementary School Principals, 57(4), 22-27.

Hazen, B. (1983). Tight times. Ill. T. Hyman. New York: Puffin.

WOW Stories, Volume I, Issue 3 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi3.