The Power of Power in Responding to Literature

By Kathryn Tompkins, Third/Fourth Grade Teacher, Van Horne Elementary School

As the end of the school year approached, Lisa Thomas, our project specialist, sat down with my third/fourth grade class to discuss what they had learned that year. She told them that each class in the school was writing an article for the school newspaper on a topic that they knew a lot about and that had been significant for them. She reviewed the various inquiries and engagements from across the year and then asked them to list what they saw as important insights from those experiences. We heard loud and clear that they wanted to write about power. Initially their focus surprised me, but as I reflected on the year with these students, their choice made sense.

We have been using a broad concept each year to frame our work with global inquiry at our school. Using concepts, such as change or journey, across classrooms and subject areas supports students in making connections across the different parts of their day and encourages them to develop conceptual thinking. They don’t just learn facts and procedures but connect these details to bigger ideas and to their own lives outside of school (Ericksen, 2002). We decided to use power as our concept because we had noticed students’ interest in issues related to power the previous year and it made sense that power was an issue children struggled with on a continuous basis in their interactions with adults and peers in school and at home.

The teachers participating in our study of power had long discussions about power and decided to define it as the capacity to influence outcomes. We used this definition to help us in our planning of engagements and in gathering resources. We did not impose our definition on students, but immersed them in experiences so they could develop their own definitions and understandings. We began by reading books and inviting discussion about the issues in these books as a way to encourage students to identify the types of power and issues related to power.

There were several read alouds over the first few weeks of school that were significant for students. Yoon and the Jade Bracelet (Recorvits, 2008) invited students to think about the power to stand up for yourself. Yoon ends up finding self-power to get her bracelet back from another girl at her school. There was also the power of knowing one’s identity in Cooper’s Lesson (Shin, 2004) as Cooper found power in being both Korean and American. There was even the power of standing up against a “power” to not be bullied in Rebel (Baillie, 1994). The students took different perpsectives on power from each story and discussed the books in ways that helped us understand their thinking. Through these various experiences, students built more complex conceptual understandings of power that could then be used as a frame for other engagements. What I did not expect was that students, without prompting, would continue to find examples of power woven through literature all year long.

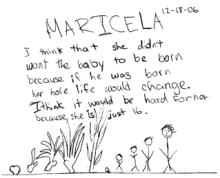

Our early discussions focused on the power in making decisions, particularly the kinds of decisions that children get to make and the ones adults make for them. The class decided they had power over things like their attitudes or who to be friends with but they did not have the power to make decisions about many things at school, such as how to do a fire drill or when they had to stop playing at recess.

Once the students had explored the power in making decisions, we moved into a discussion of the consequences that come from making those decisions. We read aloud Fox (Wild, 2001), the story of a fox who lures Magpie away from his friend, the dog, and then abandons him far off in the desert. The book was read aloud to the whole group and then they went to tables to complete flow charts showing the consequences of a decision made by one of the characters in the book. The students discussed how the bird had the power to leave the dog and faced some sad consequences when the fox abandoned her in the desert. They realized that everyone has power but some have more power than others.

After each read aloud discussion and response, Lisa took a few minutes to record students’ big ideas about power on an ongoing chart. To challenge students to pull together these insights into larger categories and ideas, the power statements from the chart were typed and cut into strips that small groups then worked together to sort into larger categories. Each group determined their own categories and labels for those categories.

This process was clearly a difficult one that students found intellectually stimulating even as they struggled with the categories and with negotiating in their groups. They had to consider power in more complex and in-depth ways and look for connections across ideas that were just lists for them. Their categories reflected the ways in which they were thinking about power. I was excited to see that each group had the same set of power statements on paper strips but grouped them in different ways, reflecting their thinking as a group. The large categories developed by each group included:

- Power can change in different ways, you always have power whether your life is good or bad, you need to have power into thinking, and power changes in different places.

- You can have power to choose and get a consequence, sharing power, some people think they have power but they don’t, when power backfires, and losing power.

- Power changes as you grow, the consequences of power, how power changes, choosing power, and unfair/mean power.

- Bad power, good and bad power, people power, choices that other people make for you, and power that we don’t know.

- Learning sequences, choices, everything is not your way, standing up for yourself, and what’s right and wrong.

- Thinking, bad things with power, change, and you have power.

- Power can be used in bad ways, changing power, different kinds and types of power, and power that doesn’t matter who you are.

- Different kinds of power, bad power, power that changes, and people having power.

After this expereince, I noticed that the concept of power was embedded in my students’ thinking and they brought this idea into many of our literature discussions in class without any prompting from me. As the students read books about hunger, such as Nory Ryan’s Song (Giff, 2000), they talked about power as a root cause of hunger. They noticed that some people had power over land, such as the English who were ruling Ireland. They had power over the streams and didn’t allow the native Irish to fish. They also had power over the land because they collected rent and kicked people out of their homes if they were unable to pay the rent. They even had power over the possessions of others because they took livestock if someone was late on rent. The livestock provided food, such as eggs, and so this action caused even more hunger. The students felt that having power went hand-in-hand with having food.

The story of a young Indian widow in Keeping Corner (Sheth, 2007) again brought up a discussion of power. Twelve-year-old Leela is a young Brahman girl who has a comfortable life. She is spoiled by her mother and loves her glass bangles and pretty saris. She is preparing to move in with her husband as they have already had their marriage ceremony. Everything in her life changes when he is bitten by a snake and dies. She is forced to “keep corner” which means she must strip herself of her precious jewelry, shave her head, and wear only dark colors. In addition, she can’t leave her house for one year, except to go to her husband’s funeral. The students were outraged at the power adults had over this young girl, and their concerns led to a discussion of having power because of one’s gender. Leela notices that if a man is widowed, he is free to go on living his life as he chooses and to remarry, but a woman’s life must, in a sense, come to an end and she is forever shunned as a widow and, therefore, considered unlucky.

The students felt that there was great power in being male in this culture. The men make decisions for Leela and she must listen to them. When Leela’s brother comes home from college to try and convince his father and uncle to allow Leela to live her life and not be shut up in the house, he is unable to convince them to change their minds and go against tradition. In researching India, students found that often men get to eat more food than women because they go out into the workplace to earn money for the family. Many students decided that the story showed that not only was there great power in being male, but there was also power in cultural customs and the beliefs that had to be followed, no matter what the consequences or the inequity.

Students also found issues of power in picture books and novels about World War II, mainly from books about the Holocaust and the Japanese Internment camps. They were baffled at how someone like Adolf Hitler could gain power over a nation, and yet as they read more about him and about that time period, they realized that there is great power in fear. Instilling fear in others is one way of gaining power over them. Hitler was able to begin his conquest by convincing the German people to fear the Jews for taking their jobs and for being “different.” Hitler then turned this fear toward anyone who was different because he could blame them for any problems that the nation was facing. The students also felt that even when people realized that what was happening was wrong, they were unable to take action because they feared Hitler and what he would do to them. A book that was particularly significant was The Terrible Things (Bunting, 1989). This book helped them realize that sometimes we don’t question power because it doesn’t affect us, but if we stand silent then we aren’t claiming our own power. They felt that power could be taken away from people like Hitler, but only if others take action.

The concept of power was even evident in writing workshop. Joey wrote that he was very upset about how some people tried to exert power over others and control them. He was particularly incensed about leaders like Hitler who needed to control others and the English who ruled Ireland in Nory Ryan’s Song. Joey could spend an entire writing session listing what upset him and the root always seemed to be issues of power.

When students began to work on their article about power for the school newspaper, I could see why these ideas flowed so easily for them. In reflecting back over the year, they decided that power means “you have control over people, land, decisions, or food.” Power comes from having money and people want power. Their ending thought was that power should be used to “benefit everyone in the world.” They understood that power is not inherently evil or bad and can be used in positive ways.

As I read their article in the newspaper, I was struck by how their understandings of power had changed throughout the year and become more complex, reflecting multiple perspectives and encouraging them to question their everyday experiences. They recognized that power is embedded in every situation, every story. They were aware that power weaves through literature and life and that each encounter provided a chance to develop new understandings and questions. By weaving this concept across the year, not only did students see connections across our different inquiries and read alouds, but they also were able to gradually build increasingly complex understandings of the issues and ideas.

A new understanding for me was the significance of staying with a sustained idea or concept over time so that students are able to move to deep understanding. So much of school involves jumping from topic to topic to “cover” the curriculum, resulting in surface-level understandings and a focus on information. My students did learn information but, more importantly, they also examined the “why” behind that information and considered the larger forces influencing their lives and the world. As they move through life, the information they learn in school will soon become outdated and replaced, but conceptual understandings about the functioning of society and people will continue to be relevant and to provide a frame for asking difficult questions instead of being satisfied to skim the surface of life.

References

Baillie, A. (1994). Rebel! Ill. D. Wu. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Bunting, E. (1989). Terrible things. Ill. S. Gammell. New York: Jewish Publication Society.

Erickson, H. (2002). Concept-based curriculum and instruction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Giff, P. (2000). Nory Ryan’s song. New York: Scholastic.

Recorvits, H. (2008). Yoon and the jade bracelet. Ill. G. Swiatkowska. New York: Frances Foster.

Sheth, K. (2007). The keeping corner. New York: Hyperion.

Shin, S. (2004). Cooper’s lesson. Ill. C. Cogan. San Francisco: Children’s Book Press.

Wild, M. (2001). Fox. Ill. R. Brooks. La Jolla, CA: Kane/Miller.

WOW Stories, Volume I, Issue 3 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi3.