Taking Action in Tight Times

By Amy Edwards, Fifth Grade Teacher, Van Horne Elementary School

Sometimes kids will surprise you. Just when you think they just don’t get it, they rise to the occasion and make you aware that they understand in ways you could never imagine. I observed my students move from a position of powerlessness to one of possibility through taking action for social justice. They were able to develop a deeper understanding of taking action for social justice because they were presented with real opportunities to address social issues that deeply concerned them (Wade, 2007).

In January our class shifted from exploring the broad concept of power to examining the power of food to influence our lives. The students had many connections to the word diet, particularly in relation to losing weight, since the TV was full of advertisements from Jenny Craig, Subway, and Nutrisystem in the post holiday season. We wanted them to talk about diet globally and locally as well as consider issues related to the power of diet and how food affects people’s lives. Our goal was to encourage them to take some kind of action to challenge their experiences of collecting canned food at Thanksgiving as requested by adults at our school. We wanted them to have a chance to come up with their own ideas about taking action that were not imposed by adults.

This semester-long project led us to understand diet, root causes of hunger, poverty and economic failure, the differences between wants and needs, and problems in the food system in our world. To make this issue real to our students we staged a global feast, where not everyone who attended got enough to eat, while others had more than they could possibly eat. Students learned that our planet produces enough food for everyone to survive, but inequitable distribution causes 30,000 children to die each day from starvation. We explored the mortality rates of different countries and even counted the calories we each ate for three days to see what it takes to maintain our health. We invited members of the Community Food Bank to speak to our students about what it means to be food secure as well as food insecure and ways they could help. We also hosted Abraham, one of Sudan’s lost boys who had relocated to Tucson, to tell his compelling story. The students kept a Hunger Journal where they noted the various causes of hunger based on these experiences, and, of course, we read and responded to books.

We explored the word diet by reading Burger Boy (Durant, 2005), a picture book about a boy who eats nothing but burgers until one day, he turns into one. Students loved this book and the discussion afterwards was fun and informative as the lesson hit home. Variety is the spice of life.

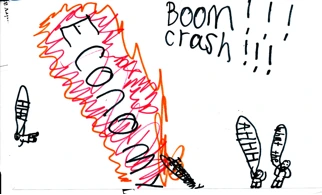

We read Tight Times (Hazen, 1979) about a family who is experiencing difficult financial problems and discussed the choices the family has to make between wants and needs. Students created flow charts that showed the consequences of tight times. They learned that hard times can bring hope for a better future as well as sadness and the loss of hope. Students engaged in Sketch to Stretch (Short & Harste, 1996), using visual images and symbolism to explore their thinking about what can happen to a family during tight times. In his sketch, AJ shows the economy crashing, writing on the back, “My picture is explaining the economy crashing. The people represent the U.S. The one flying means some people get hit harder.”

Arianna’s Sketch to Stretch shows a family happily in their home in the before picture and the same family on the street holding a sign that says “Need money” in the after picture. Arianna writes, “What I did is a before and after which means maybe you can be really rich one day, then some day else you can end up homeless.”

To further explore the difference between wants and needs, the students worked with partners to read picture books containing a range of perspectives on these issues. Afterwards they came together and discussed each book with the whole group. Thinking together the books were placed on a continuum between wants and needs. As the books were laid out, the students had to justify whether or not they belonged closer to the wants side or the needs side of the continuum. As new books were added, the books already on the continuum were shifted based on students’ discussions. The books they explored included Beatrice’s Goat (McBrier, 2001), Fly Away Home (Bunting, 1991), A Shelter in our Car (Gunning, 2004), A Castle on Viola Street (DiSalvo, 2001), Peppe the Lamplighter (Bartone, 1993), Those Shoes (Boelts, 2007), The Hard-Times Jar (Smothers, 2003), Brothers in Hope: The Story of the Lost Boys of Sudan (Williams, 2005), A Chair for My Mother (Williams, 1984), If the Shoe Fits (Soto, 2002), Homeless (Wolf, 1995), and Four Feet, Two Sandals (Williams & Mohammed, 2007). Students engaged in a great deal of negotiation and really had to think together as they debated where each book fell on the continuum between wants and needs.

Bread, Bread, Bread (Morris, 1989) was read aloud to introduce the Food Journal. The kids made many connections to the book related to the different types of breads that are eaten around the world. Students learned that calories are the energy that food provides and are needed to move and function and that protein is important as the building block for growth. They learned that food is measured in calories and protein is measured by grams. They were told that to study food around the world, they needed to study themselves first to understand what others needed to function. They were given a journal to keep track of everything they ate for three days and to record the calories and grams of protein as well. We showed them how to use the chart to determine how many calories and grams of protein are in each food item. They were also asked to add up the totals for each day. When we later examined their food journals, they discovered that they ate between 1,800 and 3,000 calories a day and that a healthy adult needs between 2,000 and 2,500 calories a day.

In February we held a Global Feast in our Learning Lab/Library. The large room was divided up into three areas. The Blue group (15 kids) represented 15% of the world’s population and got more than enough to eat. This group was served pizza and apple juice. The Yellow group (60 kids) represented 60% of the world’s population and got just enough to eat. This group was served warm rice and beans along with water. The Red group (25 kids) represented 25% of the world’s population and did not have enough food to go around. This group got one bowl of cold rice and dirty (food coloring) water. This simulation got an astonishing response. Kids realized that the world produces enough food for everyone but the food does not reach everyone fairly due to famine, war, politics, and economics. One of the biggest surprises was that hunger doesn’t just happen in other places; it is present in the United States as well. This was a huge eye opening experience for students.

Along the way students were developing a sense of responsibility and an understanding of the root causes of hunger. They were starting to understand that hunger and poverty are not the result of laziness. Homeless people are not hobos and are not all trying to pull scams. These were misperceptions students had referred to earlier in the year. Another misperception was that hunger only exits in other countries and that we should pity these people. Students realized that tight times and hunger can happen to anyone.

In March we learned about child mortality rates and the difference between chronic hunger and starvation. Scientists determine the child mortality rate from the number of children who die of hunger by the age of five out of 1000. For comparison, the children learned that the U.S. has a child mortality rate of eight per 1000. This led us to explore the root causes of hunger. To connect hunger to economic failure and poverty, we showed the students several short clips from the movie Cinderella Man about the Great Depression. The students reacted strongly as they watched the mother add water to the milk to stretch it out and the father give his small share of the food to his kids. Especially poignant was a scene where the little boy steals a sausage because he is afraid his parents will be forced to send the children to stay with wealthier relatives and so doesn’t want to ask his parents for food.

Later in March we looked at food systems, reading the book Famine: The World Reacts (Bennett, 1998) as one example of what might go wrong to prevent people from getting enough food. We looked at each of the steps food takes to get from the field to the table and what has to happen to ensure this delivery. Students charted the possibilities that might cause the system to fail and discovered that many things could happen at each stage of the food system.

In reading Sami and the Time of Troubles (Heide & Gilliland, 1992), we looked at war and violence as causes of hunger. Earlier in the year we had read books by Deborah Ellis that highlighted war as a cause of hunger in Afghanistan and so students had insights about this cause of hunger. The students also reported on newspaper articles they had been bringing on food and diet. Some of the articles were about drought in Argentina, salmonella in peanut butter, farm foreclosures, and truckers who couldn’t afford gas.

These discussions led students toward taking action. They researched organizations on the internet to see what others were doing to help fight hunger and became excited about choosing an organization to partner with in some way. They liked the Save the Children website because of the personal connection of adopting a child and talked about ways they could earn money. I did not want to dampen their enthusiasm, but was a bit worried about how we could maintain the adoption commitment after the school year ended. As it turns out, the students solved this problem for themselves.

It was about this time that a devastating event happened to one of our families. A boy in our class whose dad was out of work and had lost his health insurance suffered a major seizure and died. Many of my students knew this father because of his involvement with Boy Scouts. He picked up his son everyday on the playground after school and was a reliable chaperone for all of our field trips. The mother had recently lost her job, and was not having any luck finding a new job. On top of the emotional loss for this family, they were now dealing with serious financial difficulty. Not only was the family in danger of losing their home, they had car repairs and a family of four to feed. Loss of a breadwinner was an issue that the students immediately recognized as a cause of hunger.

Our class met several times that week to discuss what had happened and talk about why their classmate would not be at school for a while. Students were concerned about him and many attended the funeral. Our counselor talked with the whole class and later with a small group to help them process this loss. We about changes that occur in families and how we can help kids and families get through difficult times. We talked about what to say to this young student once he returned to school and what would make him feel better. Our counselor shared what other kids had told her was not helpful after they had experienced similar losses.

When it became known that this family was struggling financially, the adults in the school started to take up collections and rally some monetary support. The kids heard about these efforts and started to think about what they could do. A small group who were meeting with our counselor formulated a plan. All of these kids had suffered significant loss and were in a position to understand what our little guy was going through. One boy, Joel, who was not known for being particularly caring of others, and who was not a model student, came up with the idea of selling chips and lemonade at lunch to earn money for the family. He organized the class and created a plan. He got his dad to donate the chips and diligently followed through each day, scheduling who would be manning the table, who was in charge of the money, and who was on the clean up detail. The kids made posters, wrote advertisements for the morning announcements, and discussed strategies for maximizing sales, but it was clear that Joel was in charge. This was the most engaged and excited I had seen him that entire year. This young man was not particularly looked up to for anything except goofing off at school. He was not academically a top student and struggled with peer relationships. Taking action seemed so completely natural to him because it was personal and touched him directly. The plans for contributing to Save the Children were pushed onto the back burner. This was so much more important to our kids because there was a personal connection to the family.

Another student was so touched by this loss that he and his mom walked their neighborhood and collected donations for the family. Mark told the story of what had happened to his friend and asked his neighbors if they could help. He collected over $1000 that day. These two examples of taking action by kids were really significant. Many times adults organize events and kids witness others helping but rarely is the action kid-centered and organized completely by children.

As others at the school worked to contribute to this family, these efforts snowballed into a major event. The local natural foods store held a fundraiser for organizations once a month on Saturday called “A Buck a Burger.” A BBQ was held in the parking lot and members of an organization could buy supplies at cost and take whatever profits they made from the sale of the burgers. The store had never done a benefit for just one family but they were willing to help. The school had to supply tables, chairs, awnings, condiments, paper products, and labor. The market supplied burgers, lettuce, tomatoes, onion, and the grill at cost. We also held a bake sale in conjunction with the BBQ. It was a whole school effort and successful as 1500 hamburgers were sold that day. The newspaper covered the event and as a result of telling this family’s story, the mother was offered a job. Students participated by helping out but this event was organized by adults in our community.

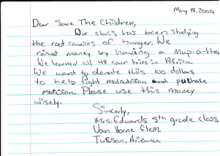

In my classroom, students were still thinking about hunger and ways to take action. They decided to hold a Map-A-Thon and collect pledges from sponsors to pay for each correct country they could identify on the continent of Africa. Initially, the money they raised was to be contributed to Save the Children. In retrospect this fundraiser was much less significant and the students only raised about $100, with me kicking in $11 to round out the donation. In discussing the practicality of adopting a child, we went back to the Web site and saw there was another way to donate that made more sense. They chose to make a onetime donation that would go towards nutrition and medicine for needy children. They wrote a letter to the organization and we sent off the check.

Meanwhile the students were still busy selling chips and lemonade at lunch. The first thing they did each morning was to check with Joel to see who was scheduled to work that day. It was such a central part of what was important in their last few days in fifth grade. Joel kept them supplied with a variety of chips to sell, never running out and never forgetting to bring them. I only wish he could have been so reliable in turning in homework! In the end, they raised several hundred dollars from their lunch sales. This experience was significant because the action was initiated and carried out by the students themselves.

Lewison, Flint, and Van Sluys (2002) point out that informed action is based in expanded understandings and perspectives. They argue that unless students have critiqued their everyday lives, considered multiple points of view, and examined sociopolitical issues and systems, the action often remains superficial and adult-directed. In our case, students had the opportunity to connect literature to issues of poverty and hunger and to consider the consequences of tight times on the needs and wants of families. These understandings provided a basis for taking action when the need arose, instead of just feeling sorry for their classmate. They took action in ways that were personal and much more meaningful than just making a contribution to Save the Children. In reflection, I realize that they did adopt a child -- one of their own classmates who needed their support and caring in a time of need.

Professional References

Lewison, M., Flint, A., & Van Sluys, K. (2002). Taking on critical literacy: The journey of newcomers and novices. Language Arts, 79(5) 382-392.

Short, K. & Harste. J. (1996). Creating classrooms for authors and inquirers. Portsmouth. NH: Heinemann.

Wade, R. (2007). Social studies for social justice: Teaching strategies for the elementary classrooms. New York: Teachers College Press.

Children’s Literature References

Bartone, E. (1993). Peppe the lamplighter. Ill. T. Lewin. New York: HarperCollins.

Bennett, P. (1998). Famine: The world reacts. Mankato, MN: Smart Apple.

Boelts, M. (2007). Those shoes. Illus. N. Jones. New York: Walker.

Bunting, E. (1991). Fly away home. Ill. R. Himler. New York: Clarion.

DiSalvo, D. (2001). A castle on Viola Street. New York: HarperCollins.

Durant, A. (2005). Burger Boy. Ill. M. Matsuoka. New York: Clarion.

Gunning, M. (2004). A shelter in our car. Ill. E. Pedlar. San Francisco: Children’s Book Press.

McBrier, P. (2001). Beatrice’s goat. Ill. L. Lohstoeter. New York: Atheneum.

Smothers, E. (2003). The hard-times jar. Ill. J. Holyfield. New York: Farrar, Straus, & Giroux.

Soto, G. (2002). If the shoe fits. Ill. T. Widener. New York: Putnam.

Williams, K. & Mohammed, K. (2007). Four feet, two sandals. Ill. D. Chayka. New York: Erdmans.

Williams, M. (2005). Brothers in hope: The story of the Lost Boys of Sudan. Ill. G. Christie. New York: Lee & Low.

Williams, V. (1984). A chair for my mother. New York: Greenwillow.

Wolf, B. (1995). Homeless. New York: Scholastic.

WOW Stories, Volume I, Issue 3 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi3.