Integrating Fiction and NonFiction Texts to Build Deep Understanding

By Lisa Thomas, Project Specialist, Van Horne Elementary School, and Kathy G. Short, Professor, University of Arizona.

Howard Gardner (1991) argues that the purpose of education is to enhance understanding. This straightforward statement challenges the current emphasis on testing and standards in schools and the resulting focus on the acquisition of knowledge and skills at the expense of understanding. This loss of focus on understanding is particularly problematic since understanding involves “making connections among and between things, about deep and not surface knowledge, and about great complexity, not simplicity” (Perrone, 1994, p. 13). These beliefs about the value of deep and complex understandings lie at the heart of our work at Van Horne, with a particular focus on developing conceptual understandings about culture and global issues.

We rely heavily on fiction to help students develop global perspectives and intercultural understanding. Stories that are authentic representations of cultures allow students to live through the characters and go beyond superficial understandings of culture. Literature can help children see how people within that culture actually think and believe and how they view their world. They can see how their own lives and needs for belonging and safety connect in fundamental ways with children in another part of the world as well as what makes those children’s lives and ways of thinking unique and distinctive. When we identify confusions or misperceptions in students’ understandings, we almost automatically search for a piece of fiction that we think will push their thinking.

Our inquiry into global issues of hunger began, like most of our work, with fiction. We knew that that students needed to develop a deep understanding of the causes of hunger to recognize possible solutions and take thoughtful action. Without a deep understanding of the complexity of the causes, social action often ends up taking the form of charity -- giving handouts to the “poor” to meet immediate needs without addressing the larger societal factors that produce the need or supporting the individuals involved in taking action for themselves (Cowhey, 2006). We consulted a range of resources, particularly a teacher resource handbook, Finding Solutions to Hunger (Kempf, 2005), to help us think about the causes that needed to be considered, and gathered picture books and novels that included food or hunger in some way within the plot.

As we discussed the causes of hunger and looked at the books, we realized that we would need to access a broader range of texts to support students in developing a depth of understanding about hunger. In particular, we needed to move from our dependency on fiction to more nonfiction and multimedia texts. We had only located a few fiction books that addressed hunger, but more importantly, we realized that students needed access to a range of resources if they were to really understand the different reasons for hunger.

Story provides a single point of view, one family or character, but our students needed a broader range of texts in order to develop an understanding of the extent of the problem in our world. Nonfiction would provide students with definitions, terminology, and facts to make the issues real; not just an interesting story, but something actually happening in the world. Through story, students come to understand the human emotions and struggles related to issues, but not necessarily the broader world context of those issues. Students needed to explore the extent of the problem of hunger in the world, especially since most had not experienced hunger themselves. Hunger affects many people in the world and the results are dire, going far beyond the stomach rumblings that our students associated with being hungry. We had also noticed that the characters in fiction usually found solutions to hunger that did not reflect the realities of ongoing chronic hunger.

Our professional inquiry as teachers focused on the roles and use of different types of nonfiction and fiction texts within the children’s inquiry into hunger. We saw nonfiction as helping students develop an understanding of the extent and severity of the problem and the lack of easy solutions, along with a recognition that the problem exists in their own community as well as in other places around the world. We believed that story humanizes numbers, but recognized that students needed the numbers in this inquiry -- they needed to know the facts. Through story, they might come to feel empathy and sympathy for those who go hungry, but still not feel the need to get involved or be socially responsible without also understanding the extent and causes of the problem.

Locating accessible nonfiction texts remained a difficult issue throughout the inquiry. The majority of nonfiction texts on the causes and experiences of hunger are written for middle school and high school students, which we took as an indication that many have underestimated the ability of young children to consider complex social issues. We found some nonfiction; mostly series books that provide information but are not particularly well written. We also found it interesting that most of these books were written and published first in the U.K., not the U.S., another indication of how American society underestimates the ability of children to consider and understand complex issues. We also located other types of texts, many of them real world materials, such as newspaper articles and brochures from agencies as well as films and guest speakers.

One source of information on causes of hunger is the nonfiction series books that are available in libraries to support students in researching a topic. These books are not well-written powerful nonfiction literature -- they are written to inform rather than to engage and so the writing is fairly pedestrian. Even so, these texts do provide access to a range of information and photographs. We used excerpts from these series books because they were the only nonfiction books that we could locate that we thought were accessible reading materials for students.

One series book that was particularly useful was Famine: The World Reacts (Bennett, 1998), which is organized around major aspects of hunger and famine around the world. Each section briefly introduces the facts related to that aspect of hunger, followed by a specific example from some part of the world. We made multiple copies of the sections that addressed the causes of hunger, such as poverty, natural disasters, war, foreign debts, cash crops, and inequality in food distribution. Students worked in small groups of four with each group reading a different section. We encouraged students to discuss the reading in their group and decide together what was most important for other students to know. The groups then each created posters to illustrate and present the important points of their section. These posters were shared in a gallery walk where students moved from table to table to examine what the other groups had learned. Through this process students were introduced to a broad range of issues on hunger as well as to the language that we would explore in depth throughout our study.

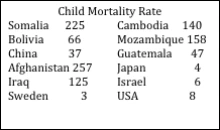

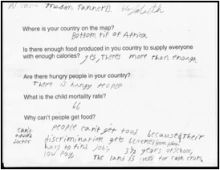

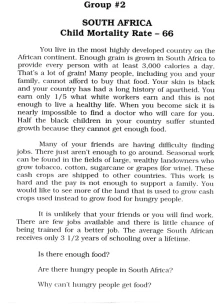

Another nonfiction text were fact cards used to support students in understanding that hunger is world wide and that food scarcity is not the primary cause of hunger. The most common myth about hunger is that people starve because there are too many mouths to feed and not enough food in the world. The reality is that there is more than enough food produced around the world to feed everyone; the issue is not the production of food but sharing that food more fairly. We borrowed and adapted an engagement from Finding Solutions to Hunger (Kempf, 2005). Students were introduced to the child mortality rate as a means of measuring the extent of the problem of hunger within countries around the world. The child mortality rate is the number of children out of 1000 who die of hunger and hunger-related diseases before the age of five. We showed students a chart of child mortality rates in ten countries and talked about what those differences meant.

Students then worked in small groups, each focusing on a fact card from a specific country. They had to determine if enough food could be produced by the country to support its population, how significant the hunger problem was within that country, and why people were going hungry. They read and discussed the fact card together and recorded their thinking about these three questions. Each group shared their findings with the class so that students could then compare issues across countries. Students were surprised to find that even in countries that they had seen as impoverished, such as India and Rwanda, enough food could be grown to feed everyone but that the land instead was used for cash crops like coffee or tobacco or the food was not equally distributed among the people of that country. They also realized that people can work hard but not be paid enough to buy the food they need and that some governments sell their food to other countries, even though that means their own people go hungry.

Another key engagement was creating a drama text where students took on roles within a global banquet. Students were assigned to three groups and given food at the banquet that reflected the world’s population -- those who have more food than what they need (15%), those who have just enough food (60%), and those who never get enough and are always hungry (25%). The 25 students who received only one small bowl of rice to share watched as 12 students each received a large pizza and another 60 sat in small groups with their own bowls of rice and beans. This drama text provided students with a concrete visualization and experience to understand that enough food does exist in the world but is unequally distributed.

These engagements provided students with information that challenged their misconceptions related to hunger and with facts about the many different reasons for chronic hunger. They helped kids understand that chronic hunger over long periods of time was the major issue, not famine and starvation. We wanted kids to do more than know that there was a hunger problem -- we wanted them to care that people are hungry in our world. We knew we needed to return to story as a way to humanize hunger.

We had not found any strong picture books with stories focused around hunger and so looked for other types of texts that might humanize hunger; specifically we looked for movies that would offer a glimpse into the life of an individual or family struggling with hunger. We decided to use excerpts from the movie Cinderella Man — the story of a boxer who loses his job during the Great Depression in the U.S. and goes from great wealth to devastating poverty. We showed three short clips from the movie. In the first, the students watched as the mother added water to the milk to make it stretch further and the father gave his share of breakfast to his daughter because she was still hungry after finishing her portion. The second clip showed the father walking past a homeless camp to a factory gate where he waits in a crowd of other men all hoping to be chosen for a day’s work. The last was a scene where the father is angry with his son for stealing salami from the butcher until the boy admits that he stole to try and keep the family together. His fear was that the father would send the children away to a farm family. Following each clip we asked the students to show their thinking through words and pictures on a large graffiti board at each table. The movie clips were a powerful text because the actors and story line drew the children into the situation. They empathized with the struggles of this family and the deep silence that filled the room after each short excerpt as children quickly wrote and drew was an indication of their emotional involvement.

After the third excerpt and response on the graffiti board, we talked together about their observations. Students’ comments focused on the father’s desire to work but inability to find a job to feed his family. They stated that he was not lazy and condemned the business owner who only hired nine workers when there were so many crowded at the gate. Other students pointed out that if the owner hired everyone, his own family would go hungry. They noted that the family didn’t have enough food; they had just enough to get by but were still hungry. One group of students had a major debate about stealing and whether it is better to steal than to die from hunger. The full extent of the impact of this movie became clear as they continued to refer to the events from the movie months after viewing the clips. They felt the family’s pain and hunger in ways that they could not put into words but that stayed with them throughout our inquiry.

Another nonfiction text was an oral story related to food distribution and food safety. This story was told through the use of visual picture cards similar to Kamishibai and a flow chart that focused on the steps involved in growing tomatoes and taking them through the food system to eventually getting them to someone’s dinner table.

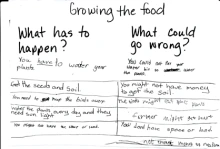

The students then broke into five small groups with each small group discussing on what had to happen and what could go wrong in the five stages of food distribution -- getting ready to grow food, growing the food, moving the food from the field, processing and selling the food, and buying, preparing and eating the food.

Students had been collecting newspaper articles about food or hunger and posting them on a bulletin board in the hallway. They examined a number of the articles to think about what aspect of the food distribution process was breaking down -- drought that was affecting a country’s ability to grow food, salmonella in peanut butter processing factories, farm foreclosures, and truckers unable to afford gas to transport food.

We continued to use fiction texts throughout the study in a variety of ways. We read and discussed stories in whole group that addressed specific issues that might cause hunger, such as Tight Times (Hazen, 1983) about a family experiencing job loss and economic difficulty and Sami and the Time of Troubles (Heide & Gilliland, 1992) about a family involved in war and conflict. We gathered a text set of picture books about families facing tight times. Students read across the texts and recorded their thinking. As a group, they then created a continuum of wants and needs to show which families were doing without things that they wanted (new shoes, a pet, or a favorite food) and which were doing without needs (food, shelter).

Another text set of picture books supported students in exploring how war can be a cause of hunger for many people in our world. While many of these stories didn’t address hunger specifically, they gave students a sense of the disruption caused by war. Students sketched or wrote their thoughts about these books on graffiti boards as they read and we then talked as a whole group about how this disruption could result in hunger.

We also scheduled guest speakers to address issues of hunger. We invited Abraham, who was a lost boy of Sudan to share his story of fleeing the war in his native country. The students had read books about this event but having Abraham talk to them in person made the experience more real. Amanda, a volunteer from the Community Food Bank, talked with the children about food security and food insecurity. She provided information about who depends on the food bank and how it works to support community members in finding food security. The children particularly noted that the food bank met immediate needs through emergency food boxes, but also provided more long-term solutions through a low cost grocery store and a food production program where people learned to help themselves through growing food in gardens.

Abraham provided a story that was compelling for the students while Amanda provided information that connected children to the problem of hunger in their community. These two guests contrasted the compelling nature of “living fiction,” a personal narrative story, with the effectiveness of “living nonfiction,” information about hunger and need. Together, these two types of texts/guest speakers gave students different perspectives on the extent of the problem and ways of taking action.

When it was time for students to make decisions about how they might take action to address hunger in our world, we turned to the internet. Using links to websites from a range of organizations, students discovered that some organizations addressed only the surface issue of money to buy food to meet an immediate need. The organizations they found compelling were those that focused on children and involved donations to purchase seeds for gardens or animals like goats and chickens as ongoing sources of food and income for families to provide for themselves.

This experience demonstrated for us the importance of using more nonfiction and multimedia texts as a way to connect the classroom with real life -- to make the context of global issues real for students and to provide the information they need to understand the causes of those issues. We also recognized that an overemphasis on fiction can cause other problems for students as readers and inquirers. Stephanie Harvey (2002) points out that 80-90% of the reading we do as adults is nonfiction -- newspapers, magazines, memos, manuals, directions, and informational books -- while elementary classrooms typically have over 80% of their reading as fiction. She argues that kids need more time to read nonfiction in classrooms to learn how to read it and make sense from it as well as to feed their curiosity, passion, and engagement with the world.

The use of such a wide range of types of texts, including drama, visual images, film clips, fact cards, guest speakers, nonfiction excerpts, and picture books provided students with multiple perspectives on the causes of hunger. This range of texts supported more diversity in the types of engagements with these texts and the use of tools to organize information, such as flow charts and T-charts. More significantly, the integration of fiction and nonfiction created a powerful context for students to build deep understanding and knowledge. They were able to connect emotion and reason, the heart and the mind.

References

Bennett, P. (1998). Famine: The world reacts. Mankato, MN: Smart Apple.

Cowhey, M. (2006). Black ants and Buddhists: Thinking critically and teaching differently in the primary grades. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Gardner, H. (1991). The unschool mind: How children think and how schools should teach. New York: Basic.

Harvey, S. (2002). Nonfiction inquiry: Using real reading and writing to explore the world. Language Arts, 80(1), 12-22.

Hazen, B. (1983). Tight times. Ill. T. Hyman. New York: Puffin.

Heide, F. & Gilliland, J. (1992). Sami and the time of troubles. Ill. T. Lewin. New York: Clarion.

Kempf, S. (2005). Finding solutions to hunger. New York: World Hunger Year (distributed by Kids Can Make a Difference).

Perrone, V. (1994). How to engage students in learning. Educational Leadership, 51, 11-13.

WOW Stories, Volume I, Issue 3 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi3.