Using the Inquiry Cycle with Young Children: A Global Study of Fairy Tales

By Jennifer Griffith, First Grade Teacher, Van Horne Elementary School

We met as a staff in January for our annual winter retreat to reflect on the fall and decide where we want to head with our kids related to our school-wide concept. In the fall we chose the broad concept of power and at our winter retreat we saw the need to bring our concept back to the forefront. We were familiar with utilizing inquiry studies, a philosophy of building a curriculum with kids, and were excited about exploring this option in both the Learning Lab and our classrooms. First we knew it was important to define inquiry for us to have an understanding of where to go with our students. Kathy Short (2009) defines inquiry as a collaborative process of connecting to and reaching beyond current understanding to explore tensions significant to the learner. Inquiry is natural to how we learn, based on connection, problem-posing and problem-solving, conceptual understanding, and collaboration within a community of learners.

Jaquetta Alexander and I had been team-teaching first and second grades and we knew moving into an inquiry study with 60 students was going to be a challenge but we were up for it. We had recently been to NCTE in San Antonio where we listened to Brian Edmiston talk about dramatic inquiry with fairy tales and young students. We were intrigued and excited about bringing fairy tales and inquiry into our classroom. We knew we needed a framework, something to provide a bigger picture for our work, and in our study group we were re-introduced to the inquiry cycle, an authoring process where learners engage in authoring or constructing meaning about themselves and the world (Short, 2009). It was this framework that set up our work with fairy tales.

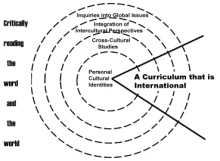

Not only was the inquiry cycle a focus for us, but Van Horne Elementary had been involved in working with Kathy Short from the University of Arizona for three years, focusing on international literature and weaving it into the curriculum so this piece of our study was just as important. She has created a framework that supports a curriculum that is international and we referred back to this model to help us set up the international piece of our inquiry.

A Curriculum that is International (Short, 2008)

Using international literature with young children can often be challenging to find the "just right" book for their level but international fairy tales were easily accessible. We were excited to work at the integration of international perspectives, where cultural views are woven into an inquiry. According to Short (2008) integrating international perspectives encourages more complexity in the issues kids consider. They are challenged to move past their own cultural perspective into more of a world view.

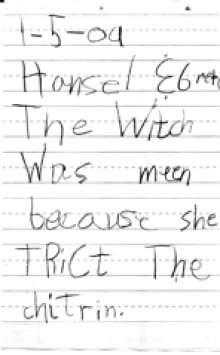

Our inquiry of international fairy tales began by using the inquiry cycle as our framework. There is a beginning point to the inquiry process and that is connections to children’s lives. According to Short (2009) connection helps kids get at the why rather than the what of a unit. Our goal was to immerse students in engagements with fairy tales so they could explore their current understandings. Our students had a background with fairy tales so we chose to spend the first week by exploring a variety of familiar fairy tales. We began our inquiry in early January, by reading Hansel and Gretel as our first fairy tale. Jaquetta and I were eager to bring in dramatic inquiry, an inquiry that invites kids to use drama to engage with a piece of literature by taking on the roles of the characters and engaging in problem solving. Edmiston (1993) argues that, “Drama enables students to respond thoughtfully and insightfully to literature” (p.250). We decided to focus on the emotions of the characters to get the kids connecting to the characters.

After every read aloud Jaquetta and I gave kids an opportunity to process and buddy buzz, a strategy that has kids turning to a partner to share their thoughts about the story -- what they noticed, connections and wonderings. After a few minutes of buddy buzz, students shared their thinking with the class. As a group we discussed the emotions the characters showed and how that might look in drama to connect with a story. Kids were engaged with this activity, always wanting to show the emotion and what it would look like. To connect to their own life experiences, we asked them to connect the emotion of the character to a time they had experienced that same emotion. We created an emotional word wall that the emotions we found that first week in our introduction to fairy tales.

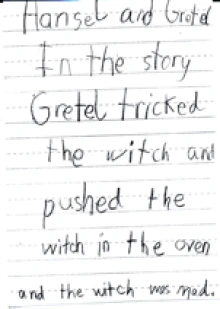

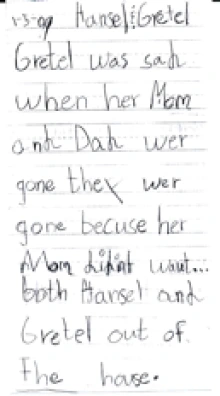

Not only did we discuss the read aloud as a class but we felt it was important for kids to have an opportunity to self-reflect on the story and make connections and noticings. We introduced them to their response logs, a place for them to do their own thinking and writing about the fairy tales. Abby wrote about how Gretel was sad when her mom and dad were gone and then went on to explain why they were gone. We had been pushing the kids to explain their thinking in order to go beyond what they thought and explain the why. It was encouraging to see the kids attempt this. Not only did Abby take the challenge but Cory did too when he talked about how Gretel tricked the witch and pushed her in the oven and because of that the witch was mad. Abbey A. used the important "because" to describe why the witch was mean. We knew we were headed in the right direction and continued to focus on giving the kids time to reflect and connect to the fairy tales we were exploring.

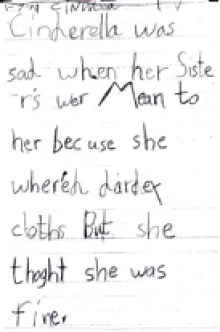

We looked at Cinderella, The Three Pigs, Rapunzel, and Jack and the Beanstalk in our first week of the study. We wanted to give kids a good background on the traditional European versions of these fairy tales and have them connect with the characters through emotions and their thinking about the stories. Cory demonstrated why Cinderella was sad when he explained that it was because her step-sisters wouldn’t let her go to the ball. Abby made the same comment and added that they were mean to Cinderella because she wore dirty clothes but Cinderella thought she was fine. The kids were not only able to explain their thinking but added additional details like Abby’s comment on what Cinderella thought about her step-sisters being mean to her.

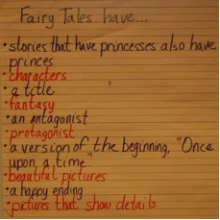

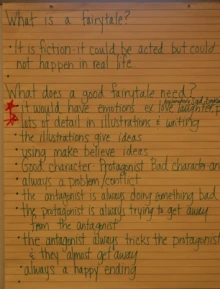

After being introduced to the five fairy tales we felt it was important for the kids to define a fairy tale so they could refer back to their definition throughout our study. We made a chart of the things they had learned about fairy tales and what they noticed as characteristics across them. They shared that fairy tales have:

- princesses and princes

- characters

- a title

- fantasy

- an antagonist and protagonist

- a version of the beginning, “once upon a time…”

- a happy ending

Through this first week of connections we wanted to provide the children with the structure of a fairy tale and so Jaquetta and I had used the terminology of antagonist, protagonist and genre in talking with the kids. As a group we put our thinking together and came up with a definition of a fairy tale -- “A fairytale is a make believe story that has a protagonist that tricks the antagonist in the end.” We referred back to this definition throughout our study to see if it still held true.

We knew after a week the kids were ready to move into invitation within the inquiry cycle. Short (2009) defines invitations as an opportunity for kids to expand their knowledge, experiences and perspectives in order to push their thinking beyond their current understandings. As teachers, Jaquetta and I knew it was our job to immerse our students in meaningful invitations to support this part of the cycle. We chose to narrow our fairy tale inquiry down to three popular fairy tales and pull in as many international variants as we could to help us develop in-depth invitations and support our international focus. We chose to study variants of Cinderella, Rapunzel, and Little Red Riding Hood.

Our 60 kids were divided into the three groups. Jaquetta focused on Rapunzel, I focused on Little Red Riding Hood and our classroom aides, Jill and Anna, focused on Cinderella. The kids spent roughly a week studying variants of each fairy tale. According to Short (2009), invitations should provide engagements that expand their knowledge to build new understandings and raise tension. With that in mind we chose to read a different variant each day, have a literature discussion, chart their "I wonder’s" and "I see’s" and then conclude with some self-reflection time focusing on perspective and emotion. After kids were done with responding we encouraged them to browse through several titles of fairy tales that we had put together in bins for them to do wide reading to engage with other variants of the fairy tale they were working with each bin holding 15-20 titles. We utilized our literacy block which was roughly ninety minutes.

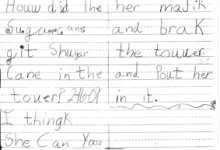

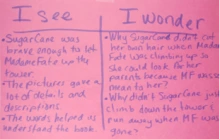

In our study group, Kathy had mentioned how a teacher in the younger grades had used a t-chart to support kids’ thinking about what they saw in a story and what left them wondering. Jaquetta and I thought this sounded simple enough for our kids but we also wanted to invite them to think thoughtfully about the story. Kids naturally would come up with an "I See" and automatically share an "I wonder" that was closely related to what they saw. An example can be seen in Jaquetta’s groups chart for Sugarcane (Storace, 2007) where a student shared that Sugarcane was brave to let Madame Fate climb up the tower. But on the flip side the kids wondered why Sugarcane didn’t cut her own hair instead of letting Madame Fate climb up the tower.

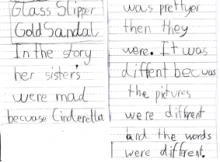

In conjunction with thinking and recording what they saw and wondered about the fairy tale the kids were also reflecting in their response logs on what they thought about the story. The use of response logs were used throughout our study. Abby began in the Rapunzel group and wrote about why Rapunzel was sad, giving details and using that important word "because." Cory was in the Cinderella group to begin with and his responses were awesome -- he was not only talking about why the stepsisters were mad at Cinderella but he compared the Cinderella we had heard during our first week, a European variation, to the one Jill read to them, an international variant goes across cultures, Glass Slipper Gold Sandal (Fleishman, 2007).

As we met and discussed our kids’ thinking and wonderings about the variants we were reading in each group we felt we had hit a wall. The kids were producing these great wonderings but we weren’t offering the opportunity for them to explore these ideas. We went back to Kathy’s chapter on inquiry, and, sure enough, tension comes after invitation, where there is a shift from teacher-guided inquiry to student-driven inquiry. It was obvious our kids had questions that needed to be answered and it was our job to encourage them to investigate their wonderings.

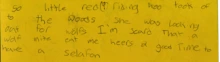

We provided students with time to do investigations through opportunities to problem-solve and explore their wonderings in more depth. At the end of the week, we asked the kids to review their wonderings and choose one that resonated with them and that they wanted to explore further. We offered several possibilities to give them an idea about what we meant by choosing something to explore. In the group I worked with, we created a chart of their wonderings from which they could choose an investigation. Some international variants of Red Riding that we read don’t depict her as having parents and many kids were intrigued by this. Others wondered why the setting was always the same. They were also interested in the different emotions of the wolf. We left the projects open ended, but did introduce several different mediums and processes they could use. Some possibilities for the first projects included drawing your wonderings, using drama to express your interpretations or blocks to build your thinking, and writing letters to the author asking them why they made particular choices.

When the projects were complete, Jaquetta and I came together to discuss the results of the projects and realized they were not what we were hoping for. We felt the kids didn’t engage thoroughly with their wonderings the way we were hoping, so we decided to rework the investigation part of the inquiry cycle by bringing in more demonstrations. We noticed that the kids hadn’t actually delved into the investigation portion of the cycle but instead focused on the representation first. Many students heard about the mediums they could use and began their projects with a focus on what they could do, instead of engaging in a dialogue about the ideas in their investigation. Jaquetta and I knew that we may have begun this process too early and that we should have given them more guidance and time to investigate their questions before introducing the projects which were actually the representation portion of the inquiry cycle. Therefore our investigations were unsuccessful the first time around.

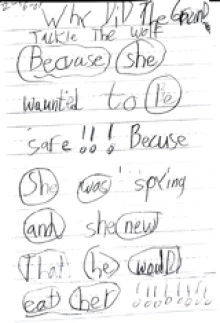

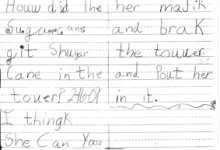

Demonstration is the part of the cycle where teachers offer support in the students’ investigations and this was the area we knew we had to revise for the kids to get the most out of their investigations. The following week we had a new group of kids exploring a new set of fairy tales but, as teachers, we each stayed with the same fairy tale to help strengthen our skills and knowledge of the stories. Doing it this way allowed us to compare and contrast the students’ engagements and wonderings in each group. After working with these stories for a week, we put the kids together and talked about what they noticed that all the stories had in common. We also asked them to think about questions they might investigate further. This seemed to make it easier for the kids to think about the stories and choose a question to explore. While thinking about the Little Red Riding Hood stories, Abby was intrigued with Little Red Riding Hood: A Newfangled Prairie Tale (Ernst, 1995) and explored the question, "Why did the Grandma tackle the wolf?" by using her background knowledge and inferences. Her interpretation was that grandma simply wanted to be safe and so was spying on the wolf and knew that he would eat her. Abbey A. was curious to know how Sugarcane got in the tower and explored that question using her knowledge and inferences as well. She thought that the sorceress, Madame Fate, used her magic to break the tower and put her in it. Giving them adequate time to engage in dialogue helped them think about their investigations with more depth. Jaquetta and I felt that having the opportunity to reflect on what the stories had in common and choosing a question to investigate produced more thoughtful, meaningful representations.

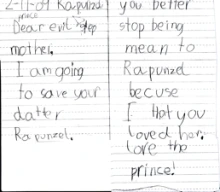

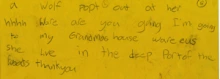

Throughout the study we continued to think about emotions the characters took on in the stories and really delved into perspectives as a way to think about others. Our response logs gave the kids that needed opportunity to pull back and reflect on their learning. It is these opportunities that fill the re-vision part of the inquiry cycle. We introduced our kids to letter writing and challenged them to push themselves in their self-reflection time by taking on the role of a character and writing a letter to another character using emotion. It was at this point in our study that we saw the kids become engaged and transfer their thinking to other content areas. The kids showed such emotion and conviction in their letters. Cory took on the role of the prince and wrote to the Evil Stepmother in Rapunzel telling her he was going to save her daughter Rapunzel and she better stop being mean to her because he thought she loved her.

We finished the next four weeks so that every kid got to experience all three fairy tales, take on the roles of characters, and investigate their questions. When each child completed studying Rapunzel, Cinderella, and Little Red Riding Hood, we felt something was missing and knew we hadn’t completed the inquiry cycle. We had encouraged kids to connect with fairy tales and use their background knowledge to further their understanding, we had invited students to expand their knowledge through responding and creating class charts on what they saw and wondered, we gave them time to ask and investigate their questions, a chance to represent their thinking and pull back and reflect in their logs. We were missing valuation and action and so again put our heads together to think about where to head next so our kids saw our inquiry all the way through.

At about this time our staff presented at the IRA conference in Phoenix and we sat in on a session about Kamishibai, a Japanese storytelling method used with young kids. We went through the process as a group of creating our own Kamishibai of The Three Little Pigs. Jaquetta and I both looked at each other with the same thought -- this would be perfect for a culminating project to finish our inquiry on fairy tales. We were thrilled to get back to school and take on this new endeavor to support our inquiry.

Valuation was where we were on the cycle, a place for the kids to step back and think about what is of value from our inquiry thus far. Short (2009) argues that valuation allows learners to reposition themselves differently in the world. So Kamishibai seemed perfect, a new storytelling method to tie into our fairy tales. Demonstrating for the kids what Kamishibai was and looked like was imperative, so we purchased several and used these to model how they worked. We created a chart of what we noticed about the Kamishibais, how they are structured, and how they differ from a book. The kids were engaged in the structure of Kamishibai and we knew they would enjoy using them in our final work with fairy tales. We reviewed what makes a fairytale by creating a chart to be used during our work with Kamishibai.

Although the valuation piece of the cycle does not necessarily mean having to do a large summative assessment that consists of a time consuming project, we felt that allowing the kids to create their own variation of one of the fairy tales through Kamishibai would be valuable. Taking on this project encouraged the kids to pull from their work and experiences with the fairy tales. In creating their Kamishibai, they were using what we had learned about emotions to express their characters’ feelings and perspectives and the characteristics of a fairy tale to help them understand and create their stories -- all within the structure of a Kamishibai. All of these components were used when working on this project. Some students chose to re-create a variant of a fairy tale they’d studied and others chose to take what they knew about fairy tales and created their own variant of Cinderella, Red Riding Hood or Rapunzel.

Part of valuation is presenting what students have learned to an audience. We had a Kamishibai party where the kids were put in small groups and parents were able to listen to what their children had learned about the process and fairy tales. It was impressive to watch these kids talk to their parents about their learning and understanding of both the Japanese storytelling method and fairy tales.

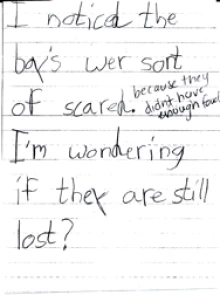

The final part of the inquiry cycle is action where we address the "so what?" of the project and think about how this will apply to our lives. It was obvious that the use of perspective and emotion were two components that kids engaged in and where we saw the transfer to other areas such as the playground and other content areas. Throughout the year the kids were able to see others’ perspectives and be compassionate to emotions of characters. We particularly saw evidence of this in their literature discussions and responses as we moved into our conceptual thinking about the power of food after we completed the fairy tales inquiry. In April, when we were discussing the Lost Boys of Sudan, Abby talked about how she noticed the boys were sort of scared because they didn’t have enough food and she was wondering if they still were lost today. So when I reflect on the last piece of the cycle it’s easy for me to see that the action part integrated into students’ thinking as they connected what they had learned about perspective, emotion and questioning from our inquiry on fairy tales into new inquiries.

Short (2009) argues that inquiry is not merely a new set of instructional practices, but a theoretical shift in how we view curriculum, students, learning, and teaching. We want to remember this as we go through the inquiry cycle, which can be daunting. Surprisingly enough, we found that as we moved through an inquiry with our students, that it was natural to progress from invitation to tension, investigation, demonstration, re-vision, representation, valuation, and action. Taking inquiry as a stance is a powerful way to move through the curriculum with students, providing the opportunity to engage in meaningful, thoughtful invitations together and to take action in their thinking and lives.

References

Edmiston, B. (1993). Going up the beanstalk: Discovering giant possibilities for responding to literature through drama. In Holland, K., Hungerford, R & Ernst, S., eds. Journeys among children responding to literature. Portsmouth NH: Heinemann.

Short, K. (2008). Exploring a curriculum that is international. WOW Stories, 1(2), https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi2/?page=5

Short, K. (2009). Inquiry as a Stance on Curriculum. In S. Carber & S. Davidson, eds., International Perspectives on Inquiry Learning (pp. 1-16). London: John Catt.

Rapunzel Text Set

Rogasky, B. (1982). Rapunzel. Ill. T. Hyman. New York: Holiday House.

Stanley, D. (1995) Petrosinella: A Neapolitan Rapunzel. New York: Penguin.

Storace, P. (2007). Sugar Cane: A Caribbean Rapunzel. Ill. R. Colón. New York: Hyperion.

Vozar, D. (1998). Rapunsel: A Happenin’ rap. Ill. Betsy Lewin. New York: Doubleday.

Wilcox, L. (2008). Falling for Rapunzel. Ill. Lydia Monks. New York: Putnam.

Zelinsky, P. (1997). Rapunzel. New York: Dutton.

Little Red Riding Hood Text Set

Daly, N. (2008). Pretty Salma: A Little Red Riding Hood story from Africa. New York: Clarion.

Emberelly, M. (1990). Ruby. Boston: Little, Brown.

Ernst, L. (1995). Little Red Riding Hood: A newfangled prairie tale. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Forward, T. (2005). The Wolf’s story. Ill. I. Cohen. Cambridge, MA: Candlewick.

Grimm, J. & Wilhelm (1993). Little Red Cap. Trans. A. Ball. Ill. By Monika Laimgruber. New York: North-South.

Harper, W. (). The Gunnifwolf. New York: Dutton.

Hyman, T. (1983). Little Red Riding Hood. New York: Holiday House.

Levert, M. (1996). Little Red Riding Hood. Toronto: Groundwood.

Lowell, S. (1997). Little Red Cowboy Hat. Ill. R. Cecil. New York: Holt.

Roberts, L. (2005). Little Red: A fizzingly good yarn. Ill. D. Roberts. New York: Abrahms.

Zwerger, L. (1982). Little Red Cap. Natick, MA: Picture Book Studio.

Cinderella Text Set

Coburn, J. (1998). Angkat: The Cambodian Cinderella. Ill. E. Flotte. New York: Shen’s.

De la Paz, M. (2003). Abadeha: The Philippine Cinderella. Ill. Y. Tang. Auborn, CA: Shen’s.

Fleischman, P. (2008). Glass slipper, gold sandal: A worldwide Cinderella. New York: Holt.

Greaves, M. (1991). Tattercoats. Ill. M. Chamberlain. New York: Potter.

Hickox, R. (1998). A Golden Sandal: A Middle Eastern Cinderella. Ill. W. Hillenbrand. New York: Holiday House.

Hayes, J. (2000). Estrellita de oro: Little Gold Star. Ill. G. & L. Perez. El Paso, TX: Cinco Puntos.

Karas, G. (1994). Cinder-Elly. New York: Viking.

Louise, A. (1982). Yeh-Shen: A Cinderella story from China. Ill. Ed Young. New York: Philomel.

Lowell, S. (2000). Cindy Ellen: A wild western Cinderella. Ill. J. Manning. New York: HarperCollins.

McClintock, B. (2005). Cinderella. New York: Scholastic.

Martin, R. (1992). The Rough-Faced Girl. Ill. D. Shannon. New York: Putnams.

Perlman, J. (1992). Cinderella Penguin. New York: Viking.

Pollock, P. (1996). The Turkey Girl: A Zuni Cinderella story. Ill. E. Young. Boston: Little, Brown.

San Souci, R. (1998). Cendrillon: A Carribean Cinderella. Ill. B. Pinkney. New York: Simon & Schuster.

San Souci, R. (1994). Sootface: An Ojibwa Cinderella story. Ill. D. San Souci. New York: Doubleday.

Sierra, J. (2000). The Gift of the Crocodile: A Cinderella story. Ill. R. Puffins. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Winthrop, E. (1991). Vasilisa the beautiful. Ill. A. Koshkin. New York: HarperCollins.

WOW Stories, Volume I, Issue 3 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi3.