Exploring World Languages in an After School Language Club

By Lisa Thomas, Project Specialist, Van Horne Elementary School

Language is at the heart of the human experience. We know that understanding language is an important part of understanding cultural identity because the way that people view and interpret their world is reflected in their language (Banks, 2001). For three years we have worked at Van Horne to develop intercultural understandings using children’s literature. As we gather books to support our inquiries into other cultures, we intentionally include texts in the languages of those cultures. We learned early in this work that students find the world languages represented in these books compelling and return to them over and over to try to make sense of the symbols and structures and to compare the new language to what they know about English.

Our students’ interest in world languages has caused us to inquire into language study practices in other elementary schools and to consider expanding our curriculum to include language study. We found several models that schools use to engage students in world language study, choosing the one that best matches their resources, beliefs, and goals. One model is Language Immersion which provides content area instruction in specific target languages. Students are taught math or science in a target world language for between 50 and 80 percent of their school day. A second model is a FLES program where language is taught as a separate subject. World language classes in FLES programs are typically taught for about 30 minutes a day, three to five days a week. A third model is a FLEX program which focuses on exploring target language/s through a collection of group engagements and independent activities. Many proponents of foreign language instruction dismiss FLEX programs, arguing that Immersion and FLES result in greater language fluency. While we agree that students won’t become fluent speakers of a new language through a FLEX program, the after school FLEX classes at our school are valuable learning opportunities because they compliment and enrich our cultural studies and generate an interest in studying a range of languages.

We decided to begin our world language exploration at Van Horne by creating an after school language club. Holding the club after school was less disruptive to classroom schedules but meant that we had to create, structure, and plan engagements that were appropriate for children who had already been in class all day. Our students work and study hard during the school day and we believe that, because they are children, their after school time should be playful. Participation in the Language Club was a choice and so we hoped that children would want to join us and look forward to attending each week. We intentionally planned experiences that children would find interesting and fun.

Our focus in the club was on language exploration within a cultural context. We envisioned a club where children were invited to sample a range of languages across multiple aspects and across multiple cultures. Their experiences in the club would be broad and varied; an opportunity to consider and compare. We knew that the language club experiences would only touch the surface of culture, but would compliment the deep explorations of culture that our students experience as part of our regular school curriculum.

We also didn’t expect that students would become fluent speakers of a new language during the club. Our goal was to promote interest in world languages through games, cooking, songs, story and drama. Our hope was that this interest would result in a more focused study of a world language in the future. We saw the language club as the school’s first step toward more comprehensive language study opportunities in the future.

Jenny, arts integration specialist, and Lisa, librarian, organized and facilitated the Language Club. We are both native English speakers so we needed guest experts who were native speakers of world languages. We employed the help of international students from the College of Education at the University of Arizona. Three graduate students expressed an interest: Ke, from China, was our Mandarin expert, Junko, from Japan, taught Japanese, and Dan, who moved to the U.S. from South Korea as a teenager, taught Korean. It was significant that our students had the opportunity to work with and learn from these specialists over time. In school settings guests typically visit for one day. This can result in the sense that they are on display and leave students feeling as if these international visitors are exotic. Working with the language specialists over time gave our students the rare opportunity to develop relationships with people from other countries and cultures.

In introducing herself at a conference, Korean-American author, Linda Sue Park, said, “My parents are from Korea. It is near China and Japan but it is NOT China or Japan.” This point of view resonates for us as we work to help our students understand that countries that are close to each other geographically may share some physical and cultural characteristics but each is distinct. Outsiders to those cultures tend to generalize and stereotype all people from Asia as one group. In the beginning stages of our planning we thought that it would be effective to have language specialists from different parts of the world. It was a happy accident that the graduate students who first showed an interest all came from different countries in Asia. As our students developed relationships with Ke, Junko, and Dan, they began to see the connections and distinctions between the peoples and cultures of China, South Korea, and Japan. Later, when another university student from Taiwan visited the club, they realized that there are differences within Chinese cultures.

Students in first through fifth grade were invited to participate in the Language Club. We limited participation to 50 students and the spots filled up quickly. The tuition was fifty dollars for ten weeks but we were able to offer scholarships to families that needed them so no one was turned away because of their inability to pay the tuition. The club met on Wednesday afternoons for 90 minutes. Each meeting included a story time, language lesson, and centers.

We began each club meeting with a snack and whole group story time. We selected literature written in the native languages of our specialists. Dan, Ke, and Junko helped us locate books that were originally published in China, Japan, or South Korea with stories that authentically represented the cultures within these countries. Some of the books had been translated into English, some were in the original language, and some were bilingual. The students enjoyed listening to the stories in their original language, relying on the illustrations to make sense of the story. At times we read the book in both the world language and English. The children were curious about the patterns and repetitions that they heard as the specialists read and they asked many questions, trying to make sense of the structures and sounds within the language. It was evident that they were connecting the new language experiences to what they knew about English.

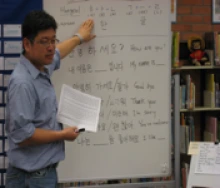

The students were divided into three smaller groups for language lessons. Each group was taught by a different specialist. Ke, Junko, and Dan planned lessons that introduced specific types of vocabulary or engaged students in a more focused look at some aspect of their native language. During the first three weeks of language club students rotated through all of the languages get a taste of each and to allow them to see the distinctions between these three different, but connected, languages. After this introduction we asked the students to choose the language that they most wanted to study for the remainder of the club. This gave our specialists a chance to connect one week’s lesson to the next and provided more focus and continuity for the children.

During language lessons, Junko, Ke, and Dan taught the words for family members using family tree diagrams, introduced games that required students to combine number words with words for facial features and body parts, taught word patterns that are used for large numbers, and shared the origins of the written symbols, encouraging students to form the word with their bodies. Students learned songs that the specialists had sung as children, practiced writing their names in the languages, wrote words that are commonly used at school, and read simple phrases, stories and poetry in the new languages.

After the language lessons we invited students to choose from a range of small group language centers. This was a chance to explore across the languages and cultures represented by our language specialists through art, games, music, movement, technology and cooking. Each individual center emphasized one of the three languages or an engagement from one of the countries and students were free to go to the centers that they found most intriguing. We relied on our specialists to plan center engagements that were culturally relevant and tried to choose experiences that encouraged students to speak or write a new language in some way. Each language specialist worked at one of the centers, while Jenny and I facilitated the other choices.

During center time the children were invited to learn about the Chinese art of cut paper with Ke. They dressed in traditional Korean clothing with Dan. They learned to use chopsticks with Junko. Students played games from each country, surfed websites, prepared sushi, mandu and egg drop soup, created a range of folded paper art, wrote using bamboo brushes and ink, and created watercolors inspired by music and images from all three countries.

Many of the center engagements came from the childhood experiences of our language specialists, making them more than fun activities from a strange land for the children. The songs, games and projects were an authentic part of the identities of our specialists and a reflection of what was important in their lives. The personal stories they told around the projects that the students did at each center deepened the cultural significance. Using chopsticks is a part of Junko’s identity, so learning to use them from Junko gave students insight into her as a cultural being. As Dan helped the students try on his own children’s traditional Koran clothing, they came to understand how Korean traditions play a role in his life as a Korean American father. Using short video clips from YouTube of Chinese students doing morning exercises, Ke shared her experiences as a young school girl in Beijing. Students associated the center engagements with the identity of the language specialists rather than seeing them as exotic, isolated practices from another part of the world.

Our students didn’t become fluent speakers of any of the languages that they explored during the Language Club and we didn’t expect that they would. (They did learn and use more words in each language than the Jenny and I!) But, this introduction into the language and culture of these three countries accomplished what we hoped -- our students recognized similarities and distinctions across the cultures. They had the opportunity to meet and develop a relationship with people from other parts of the world. Finally, students developed an awareness of and interest in a world language that might lead to deeper language study in the future.

The parents in our community were pleased that their children had this opportunity to explore Chinese, Japanese, and Korean. Many have asked us to offer the after school language program again. We are interested in finding languages specialists from other parts of the world to expand our students’ experiences with world languages.

The success of our brief exploration of language inspired our staff to look closely at ways to develop second language fluency in students at Van Horne and we began reading professional literature about world language instruction. We learned that in addition to opening the door to other cultures and helping a child to understand and appreciate people from global cultures, becoming bilingual and biliterate would benefit our students in a number of significant ways. Cognitive research shows that second language learning has a positive effect on intellectual growth and enhances a child’s mental development. Students who learn a second language develop flexibility in thinking, greater sensitivity to new language learning, and a better ear for listening. Students who study a second language in elementary school have improved overall school performance and superior problem-solving skills (Suarez-Orozco & Sattin, 2007).

Technology and economic interdependence have made the world a smaller place. Never before have so many people from different countries been able to come together to share knowledge and do business (Stewart, 2007). We want the students at our school to be able to interact successfully in this interconnected world and we believe that the ability to speak more than one language will help them achieve this success.

We are in the process of securing the resources necessary to offer Spanish and Mandarin language immersion programs at Van Horne so that our students will have the opportunity to become fluent in a second language. In the meantime, we will continue to offer our afterschool language program and give our students a chance to play with a wide range of languages taught by people from around the world. This experience will broaden students’ experiences and open their minds to the world.

References

Banks, J. (2001). Cultural diversity and education. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Suarez-Orozco, M. & Sattin, E. (2007). Learning in the global age. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Stewart, V. (2007). Becoming citizens of the world. Educational Leadership, 64(7), 8-14.

WOW Stories, Volume I, Issue 3 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi3.