The Significance of Perspective in Exploring International Literature with Educators

By Kathy G. Short

Courses and workshops on international literature for teachers and librarians have become increasingly popular in recent years in response to the growing availability of these books and the emerging interest in global education. Because of the complex issues that surround global education, these courses must go beyond immersing educators in the books. Becoming familiar with international books is a first step in a much more complicated process of challenging educators to consider issues of cultural authenticity and the types of engagements with these books that build intercultural understanding, not stereotypes (Short, 2011).

The first time that I taught a course on international literature, we took on a different continent each evening, meeting in literature circles for small group discussions of books from that part of the world and reading Bookbird articles written by authors from those cultures. This broad survey of literature from the world was interesting and a range of perspectives and writing styles were evident in both the professional articles and the children’s literature. The struggle for me was that we stayed on the surface of each culture through this survey approach, instead of digging more deeply. Class members gained a sense of the types of books available in different regions of the world and the issues for each of the regions, but we only had a week with each book or set of books before moving on to the next continent. We gained a breadth of reading experiences, but we sacrificed depth and critical thinking.

The value of a cross-cultural study is the opportunity to focus deeply on one culture to understand its complexity and diversity, so the next time I taught the course we engaged in an in-depth study of Korean culture for several weeks. We read and discussed When My Name Was Keoko, by Linda Sue Park (2002) about her parents’ experiences during the Japanese occupation of Korea during World War II. We responded to this book in a range of ways, including creating cultural x-rays of characters to show the external features of culture that were visible to others as well as the internal values and beliefs within the heart of that person. We compared the perspectives in this book to two other books from the same time period, So Far from the Bamboo Grove (Watkins, 1993), a memoir by the child of a Japanese officer in Korea, and Year of Impossible Goodbyes (Choi, 1991), a memoir of a North Korean child. Comparing the perspectives in these three novels provided strong evidence that authors’ life experiences influence the stories that they tell. In addition, we created a jackdaw, a box of information, newspaper articles, maps, photographs, and artifacts relating to the time period and events in these books. Each person took an issue or event that intrigued them and did further research on the internet to identify an artifact to share and add to our jackdaw. Jackdaws are a teaching tool that connects historical books with real events of the time through concrete objects (Lynch-Brown & Tomlinson, 2007).

|

|

|

We also browsed and read picture books about Korea published in the U.S. and compared these with picture books from South Korea. An international student from South Korea shared her collection of picture books currently being published in that country and talked about her analysis of these books and the changes in literature for children within South Korea. This experience brought to the forefront the problem of the dominance of folklore and historical fiction in books available in the U.S., resulting in outdated images of life in that country, as compared to the many contemporary images of life in the South Korean books. It also led to discussions about translated books and the issue of which books are chosen for translation into English and who makes that decision.

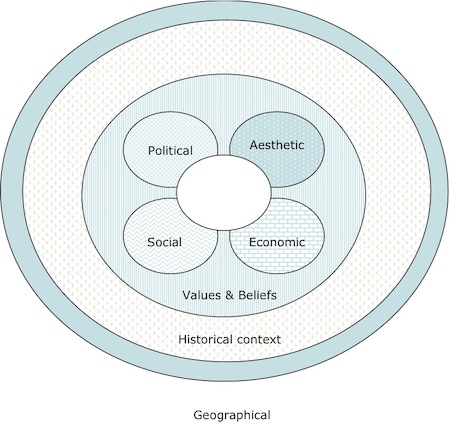

We ended our study by looking at the Begler (1996) model, which provides a frame for examining the complex factors involved within any culture. The model indicates that all cultures exist within a historical context that shapes the cultural forms and systems and operate within a geographical context that involves constant interaction and adaptation. Begler also argues that all cultures serve five basic sets of functions–economic, social, political, aesthetic, and values/beliefs. These values and beliefs shape behavioral norms and provide meaning to human activity within cultures. We made a large poster-sized version of this model and recorded our current understandings about Korean culture on post-its, placing them on the model to gain a sense of what we understood and what was still missing from our understandings.

We did follow the Korea study with several class sessions where we looked across other global countries and cultures to get a sense of how these cultures are represented in children’s and adolescent books available in the United States. Engaging in the Korea study meant that this survey of cultures had to be condensed and was less comprehensive; however, the Korea study provided for a depth of thinking and a range of perspectives that helped teachers develop strategies for critically considering other texts from global cultures. We realized that reading one text in isolation from other texts and without some knowledge about a culture was dangerous and could easily lead to misconceptions and stereotypes.

Critically reading books set in global cultures is difficult when readers have only surface knowledge about those cultures. The next time I taught this class, I decided to have teachers always read a book in the context of other books to provide us with perspectives that facilitated more critical reading. In particular, we read paired books that were from the same culture or had similar themes, but provided differing perspectives. These pairings often exposed problematic issues, such as the domination of western views or assumptions about race, class or gender. Dan Hade (1996) argues that paired texts can provide the means for readers to read critically and to uncover stereotypes within literature for themselves instead of teachers imposing their views about particular books. He paired books with problematic stereotypes with books that challenged those stereotypes, such as pairing The Giving Tree (Silverstein, 1964) with Piggybook, (Browne, 1986) as a way to encourage discussions about gender stereotypes.

In the course, the books in each pair were selected to reflect opposing points of view and so we were able to read the books against and beside each other, which supported us in uncovering problematic issues. Initially, I was concerned that class members would resist having to read two novels in one week, but the rewards of reading paired texts led them to ask for more paired texts. We learned how to read critically as we read globally.

One effective paired book set was Homeless Bird (Whelan, 2000) and Keeping Corner (Sheth, 2007), novels about young girls who become child widows in India. Both books received starred reviews and are considered well-written, powerful novels, but differ in the source of their authorship. Whelan brings an outsider perspective to writing about India, which she came to know through research and traveling to the culture in her mind, while Sheth was born in India, came to the U.S. as a young adult, and grew up with a great-aunt who was a child widow. Our discussion focused on the differences in how the stories are told, not in judging the books as good or bad because of outsider/insider distinctions. We explored differences in what came to be represented in the books through the differing perspectives of the authors.

|

|

As we gathered in literature circles, many talked about finding Homeless Bird personally moving with an inspiring message. Then they read Keeping Corner and were struck by the rich details of daily life and culture that were missing from Homeless Bird. In fact, we realized that Homeless Bird read more like a fairy tale, with a focus on plot and a lack of detail about setting. The main character is caught in a downward spiral of negative events that pile up one after the other with stock characters like the evil mother-in-law, a “prince” who takes her away, and a happy ending. This fairy tale strategy made sense, since the author did not have intimate lived experiences in that culture. In contrast, we felt embedded in Leela’s life, culture, and time in Keeping Corner. We were immersed in her story of gradual awakening to issues of tradition, independence, and women’s rights. We lived the story with her rather than observing her story from a safe distance as we did with Homeless Bird. We knew the character in a more intimate way and were still with her as the story ended with hope and promise, but uncertainty.

This experience convinced us on the power of reading books alongside each other and we went on to explore other types of paired books:

•Books with a similar theme, one set in a global culture and the other in our own familiar culture, to facilitate connections, such as The Composition (Skarmeta, 2003), set in the dictatorship in Chile with Friends from the Other Side (Anzaldua, 1997), set on the U.S./Mexico border, to consider issues of fear and the use of police intimidation. Another example is reading The Shadows of Ghademes (Stoltz, 2004), set in Libya, with Nightjohn (Paulson, 1993), set in the U.S, both of which include reading as resistance and as freedom within oppression during the 19th century. Barbara Lehman, et al. (2010) has written about this type of paired book as a means of encouraging readers to see their lives connected to the issues in a book outside of their culture.

•Books that contrast differing perspectives on the same historical event, such as When My Name was Keoko (Park, 2004), a Korean perspective on the Japanese occupation of Korea during World War II, and So Far from the Bamboo Grove (Watkins, 1986), the memoir of a Japanese child whose father was an occupier.

•Fiction and nonfiction on the same event and time period to provide a rich informational context for a story, such as Nory Ryan’s Song (Giff, 2002) with Black Potatoes (Bartoletti, 2005), on the Irish Potato Famine.

•Books with a similar theme, such as the need for belonging and relationships, as a way to examine connections and differences across cultures in relation to that theme, such as The Crow-Girl (Bredsdorff, 2004), set in Denmark, and Wanting Mor (Khan, 2009), set in Afghanistan.

•Historical and contemporary stories of the same global culture to explore the dynamic and changing natures of cultures, such as Wanting Mor (Khan, 2009), a contemporary novel, and The Shadows of Ghademes (Stoltz, 2004), set in the late 1800s. Both focus on Muslim girls within Middle Eastern countries.

As we read these pairs, we were intrigued by how our understandings of a book shifted when that book was juxtaposed with different books. The significance of perspective quickly became clear—the most interesting pairings were ones where the two books offered distinctly different perspectives on a particular event, culture, theme, or issue. The two books need to challenge each other in some way, not simply be connected by a surface-level topic.

We needed a range of strategies for reading these paired books. One strategy is to ask everyone to read both novels during the same week. These discussions were compelling as students discussed reading the books against each other and compared differences in their reading experiences depending on which book they chose to read first. When we read the paired sets of informational books with fiction novels the same week, readers decided which to read first based on their own reading preferences. Those who were strong nonfiction readers found that reading the informational book first caught their attention and led them into the novel, while the novel readers needed the story in order to get them interested in the information. We found that the order in which we read books affects our interpretations and understandings.

Reading two novels a week along with professional readings was a heavy load so we played with multiple ways of reading paired books. One was to read one book the first week and then the second book the next week, which provided for a stronger contrast of the differing perspectives across the books. Another strategy was to have four small groups each reading a different novel related to the same theme, in our case the theme of literacy. Students first met in small groups to discuss their novel and to develop webs of the significant themes related to literacy. We reorganized into text set groups with one person from each novel group in a new group where everyone had read different novels. They shared the central plot and themes of their books and looked for connections and comparisons on literacy across the books. A variation of this was that we read two novels with the class split in half and so first met in small groups for discussion, then paired the two groups who had read the same novel for a comparison of the ideas developed in their small groups, and finally met as a class to compare the two books.

We also took the responsibility for finding our own paired books after a number of experiences with paired novels that I had put together. When we read different translated novels for small group discussions, students brought one or two books that they thought would pair well with their novel in offering a different perspective, and shared those books in their literature discussion. The task of searching for books connected to issues or themes in the novel, but provided a different perspective, creating deeper understandings and insights into the novel. When we read historical novels from a range of countries, students engaged in internet research on the time and place and brought that information to the literature circle.

Finally, another important strategy was pairing novels with professional readings. For example, we read novels in which the characters engage in cross-cultural experiences, moving from one culture to another, such as Benny and Omar (Colfer, 2007) and Hannah’s Winter (Meehan, 2009). These novels were paired with professional readings on intercultural learning by Case (1991) and Fennes and Hapgood (1997). We met in small groups to discuss the novels, followed by a discussion of the professional readings. Students then returned to their literature circles to analyze the intercultural learning of the main characters in relation to the professional readings.

In addition to these strategies for engaging in the reading, we used a range of response strategies to help us see connections and differences across the books. These strategies included Venn diagrams, webs, t-charts, and comparison charts. For one set of books, we created heart maps for the two main characters in the two novels to show the values and beliefs at the heart of each one and then cut out the hearts and positioned them to show how much their hearts did or did not overlap. For another paired set, we created a three column chart to show how the two books Connect to each other, Extend each other, and Challenge each other.

The key to effective paired books is perspective, not finding the right answer or point of view, but considering multiple, even opposing, views on the same event or issue. Reading paired books with differing perspectives challenges us to recognize our own views as only one of many possible perspectives, instead of as the norm. Whether we shift our beliefs or not is not the point, just knowing that other alternatives exist provides for a deeper understanding of our lives and world.

Engagements with international and global literature open the potential for transforming readers’ perspectives through thoughtful dialogue and responses to these books. These interactions invite educators and students to reflect on their own cultural experiences and to imagine global experiences that go beyond themselves. All readers need to find their lives reflected in books, but if what they read only mirrors their own views of the world, they cannot envision alternative ways of thinking and living and are not challenged to confront global issues. The challenge is to find ways to open up safe spaces that invite educators to experience the power of this literature for themselves so that they, in turn, take the risk of inviting their students to join with them in building bridges across global cultures.

References

Begler, E. (1996). Global cultures: The first steps toward understanding. Social Education, 62(5), 272-276.

Case, R. (1991). Key elements of a global perspective. Social Education, 57(6), 318-325.

Fennes, H. & Hapgood, K. (1997). Intercultural learning in the classroom. London: Cassell.

Hade, D. (1997) Reading multiculturally. In Violet Harris, ed., Using multiethnic literature in the K-8 classroom. Boston, MA: Christopher-Gordon.

Lehman, B., Freeman, E., & Scharer, P. (2010). Reading globally, K-8. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Lynch-Brown, C. & Tomlinson, C. (2007). Essentials of children’s literature, 6th Ed. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Short, K. (2011). Building bridges of understanding across cultures through international literature. In A. Bedford and L. Albright, eds., A master class in children’s literature: Trends and issues in an evolving field. Urbana, IL: NCTE.

Children’s Books Cited

Anzaldua, G. (1993). Friends from the other side. San Francisco, CA: Children’s Book Press.

Bartoletti, S. (2005). Black potatoes. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin

Bredsdorff, B. (2004). The Crow Girl: The children of Crow Grove. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Browne, A. (1986). Piggybook. New York: Knopf.

Choi, S. N. (1991). Year of impossible goodbyes. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Colfer, E. (2007). Benny and Omar. New York: Hyperion.

Giff, P. R. (2002). Nory Ryan’s song. New York; Delacorte.

Khan, R. (2009). Wanting mor. Toronto: Groundwood.

Meehan, K. (2009). Hannah’s winter. LaJolla, CA: Kane/Miller.

Park, L. S. (2002) When my name was Keoko. New York: Clarion.

Paulson, G. (1993). Nightjohn. New York: Delacorte

Sheth, K. (2007). Keeping Corner. New York: Hyperion.

Silverstein, S. (1964). The giving tree. New York: Harper & Row.

Skarmeta, A. (2003). The composition. Toronto: Groundwood.

Stolz, J. (2004). The shadows of Ghadames. Trans. C. Temerson. New York: Delacorte.

Watkins, Y. (1993). So far from the bamboo grove. New York: Perfection Learning.

Whelan, G. (2000). Homeless bird. New York: Harper.

Links to Blogs: The Importance of Paired Books

Strategies for Reading and Discussing Paired Books

Text Sets as Contexts for Understanding

Paired Books: Reading a Book in the Context of another Book

Never Read a Book Alone

Kathy G. Short is a professor in the program of Language, Reading and Culture at the University of Arizona. She is Past President of USBBY and director of Worlds of Words. This vignette is based on blogs published on WOW Currents in February 2011.

WOW Stories, Volume III, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesiii2/.

Children’s literature is one of the most important ways the we can express values as well as the values of other cultures through print. It would be a great way to compare and contrast what we hold as our cultural values here in the U.S. with those of the cultures we examine through international literature. How can children learn different view points as well as how to respect those viewpoints? How can children learn that the world is a much bigger place than the classroom, school, state, or country? For most, international literature holds the answer as well as the key to unlock those doors. TV is probably the other way, but how rich a resource we have with a book

I appreciate having some how-to steps outlined for using multicultural & international lit in the classroom. It seems so obvious and straight-forward as I read, but without guidance like this I know I’d be floundering. I’m wondering about the Hancock quote, “Moral background becomes an influential part of response to the actions and decisions of characters in literature. Readers measure the right and wrong of characters against their personal value systems.” I like the emphasis on having students articulate the values they glean from a story, rather than on the values a teacher sees, and/but I’m wondering in light of Hancock’s observation if there is a skillful way for teachers to model how bias/stereotyping/cultural difference/over-generalizing factors into what-how we see & name values? Has anyone tried an approach like this?

My above comment was suppose to follow the article about using multicultural and international lit by Deanne Paiva. Sorry for that confusion!

I appreciated how this article focused on how being a holistic teacher requires the provision of holistic/creative/broad writing responses. It is true that a range and choice of expressive forms will allow student to demonstrate their knowledge (or lack of) most vividly. It is always helpful to see examples of new expressive strategies–THANKS!

And yes — like in Finland, all teachers should be empowered to realte lessons to community issues & knowledge!!!

I am posting to this article, as for some reason what I wrote about the other article posted here.

I found this article much more interesting than the other one. I particularly enjoyed to writing samples by children, as I used to be a bilingual writing specialist. It is as interesting to read what children say in word as much as it is interesting to see how they respond through picture. Building on prior knowledge about refugees and experiences is a great way to begin a discussion about this topic.

I also like the theme of children’s life journeys. It is a new concept since children aren’t viewed as having much of a life journey being only alive a few short years, yet they have as interesting a story to tell as adults through writing.

I like the idea of taking into account the child’s family background, community, etc. in both the home country and the new country. This makes it much more interesting but also tells a much deeper tale. It connects the old with the new in a sense, but also has continuity. Reading and writing about these experiences is very important in a multicultural curriculum. International children’s literature plays a key part in this at all levels. The refugee experience is unique in this connection.