Identity through Global Literature: Pre-Kindergarteners Learn About Themselves in the Sonoran Desert

Jane Metzger, Jennifer Hook, Vanessa Ruiz

Creation School is nestled in the hills of the Sonoran Desert in the Rincon Mountains of southern Arizona, just east of Tucson. We teachers strongly believe that children gain much from connecting with the natural wonder around them. Our guiding philosophy states that children learn through exploration and make sense of the world through intellectual discovery; the physicality of their bodies; an emotional connection to adults and peers; their understandings of themselves and their place in the community; and, the wonder and appreciation for the miracle of creation and its Creator.

The families attracted to what we offer at Creation School tend to be middle to upper class families with many stay-at-home mothers. Parents work as engineers, in the medical field, or the military. The faith curriculum is important to them, and they recognize the value of hands-on learning. Because of the military population, some children have experiences from many geographic locations. English is the first language of the majority of students but a few speak Spanish or another language (i.e., Dutch) at home/school. We have a strong representation of Asian and Latinx students, though the majority are European American.

Growing Identities through Story

We are three pre-kindergarten (pre-k) teachers of four and five-year-old children who attend school three to four days a week. When we first met with the other teachers in our Global Literacy cohort, we were excited about the idea of exploring identity through story. Our theme verse for the 2019-2020 school year was “Let the Redeemed of the Lord tell their story” (Psalm 107). We felt that our identity was first as children of God. The children were developing their own identities through their interactions with their families and communities and we hoped to enhance and deepen their perspectives and understandings of themselves through experiences inspired by the global literature.

When we first looked at introducing identity through the lens of global literature, we discovered that our personal identities are influenced by the multiple cultures in which we live, including families, schools, geographic regions, communities, ethnic backgrounds, and religious affiliations (Corapi & Short, 2015). Up until then we had not considered where we are in the Sonoran Desert to be a culture that influences our identity. Since developmentally we knew our students needed to explore, we were excited to think about finding literature that spoke to the environment where they lived as an important aspect of their cultural identities. As Latinx children’s author, Maya Christina Gonzalez (2007), said about her own journey to identity, “I turned to my environment to search out my reflection and sense of belonging. The amazing desert sunset taught me that there is beauty in the world, and that beauty made a difference” (Foreword).

Exploring the Sonoran Desert

Students began the year exploring and observing the Sonoran Desert enveloping our campus. We found where we lived in Vail on a map of the United States and saw how the Sonoran Desert was is located around us and into Mexico and California. Throughout the year, we discussed the heat, the importance of water, the monsoons, and their effect on how we live and who we are.

Keeping in mind that young children learn through their senses, we first focused on the environment out the back door of our classrooms and the stories that accompanied it. We took nature walks and students created drawings which were springboards for them to tell us what they already knew about the desert surrounding our playground (see Figure 1). For example: “You have to watch out for the jumping cactus!” exclaimed Violet, age 4.

“Those are spikes,” Caroline, age 4, added.

Riley, age 4, drew a story about a “a prickly pear cactus” she saw (see Figure 2).

Taylor, age 4, drew a story about “a cactus with sharp prickly things” (see Figure 3).

We also read many books about the desert. One favorite was Desert Night Desert Day (Fredericks & Spengler, 2011). This book is filled with lively illustrations and written in song about desert animals. Fredericks explores the differences between diurnal (e.g. gila monsters, desert tortoise, quail, deer) and nocturnal (e.g. owls, javelina, pack rats, scorpions) animals in the text. The book inspired an energetic discussion followed by a sorting activity distinguishing which species are awake during the day in the desert and which are awake during the night.

We drew on what we learned from books we read on other nature walks. We looked for the different species of plants we had identified in Desert Night Desert Day, for example, while on the lookout for diurnal animals. On our walks we saw Palo Verde trees, prickly pear cactus, barrel cactus, jumping cholla, Mesquite trees, jojoba, and saguaros. We identified the plants and discussed how they looked and how that might help them adapt to the desert conditions. The children were engaged and made saguaro cactus shadows using their arms and legs. We also saw cottontail rabbits and quick moving lizards living within the shrubs and grasses.

Another favorite book was Cactus Hotel (Guiberson & Lloyd, 1993). This book broadened our Storying Studio curriculum by further investigating the saguaro cactus life cycle and the animals that find refuge within its fragile ecosystem. Students studied the grandeur of the saguaro cactus right outside the gates of our Creation School playground (see Figure 4) and integrated what they saw and had learned about it and its inhabitants in drawings in their sketchbooks. Their artwork and narratives about the saguaro and its neighboring flora and fauna connected students with their environment and our school and who they were living in the desert. We published their work in a book published by Studentreasures Publishing entitled, Our Sonoran Desert.

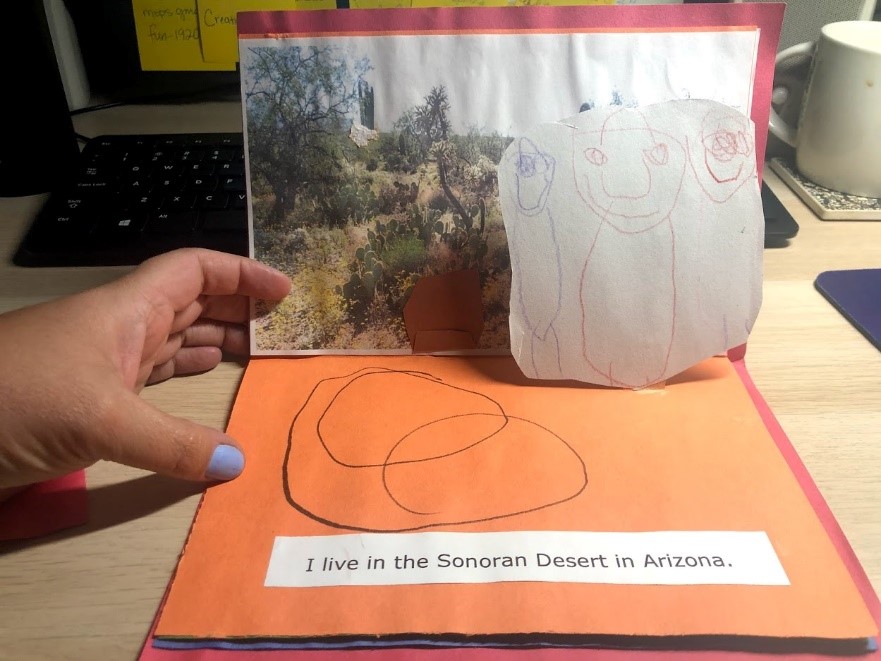

Students also enjoyed reading Creatures of the Desert World (National Geographic, 1987), an interactive pop-up book about desert animals. They took turns using the pull tabs and flaps to move and find different desert species and anticipating the next page turn and discovery. We talked about the “art smart” concepts of background and foreground which students used to create their own pop-up stories about the desert titled Where I Live to further explore their identities. Figure 5 shows Zoey’s, age 4, drawing of herself in the foreground and a boulder she cut from construction paper and glued to the desert in the background of the page. She informed us that “the desert has snakes” and also drew a snake.

Figure 5: Zoey’s drawing of herself in the foreground of the page, a bolder in the background, and a snake on the ground.

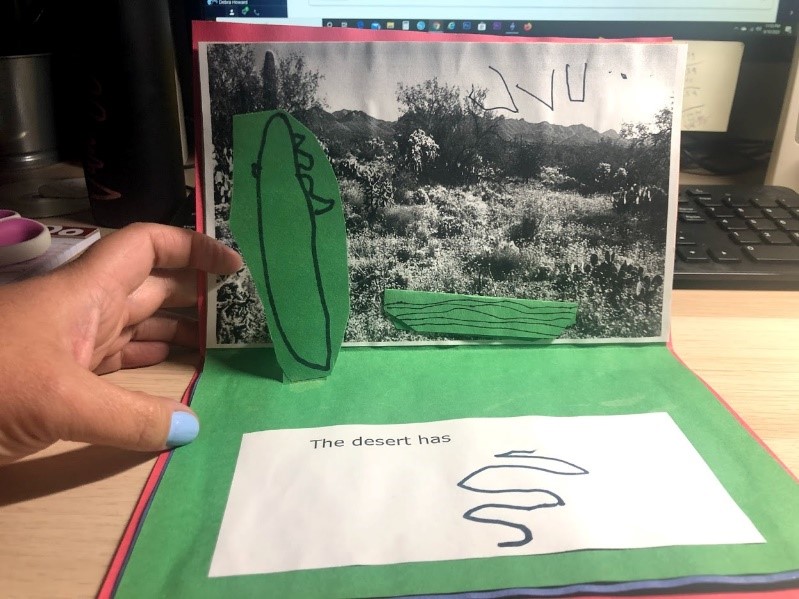

In Figure 6, CJ, age 4, drew a saguaro standing in the foreground and one that had fallen on the ground and wrote an “s” for “saguaro”. He also drew birds flying in the background.

Figure 6: CJ’s drawing of a saguaro standing in the foreground, one lying on the ground, and the “s” he wrote for “saguaro”. He also drew birds flying in the background.

Various other classroom activities helped us enhance our identity and sense of belonging to the Sonoran Desert. We read Desert Giant (Bash, 1989) and The Seed and the Giant Saguaro (Ward and Rangner, 2003). Students sculpted 3-D prickly pear cacti out of playdoh (see Figure 7) and we collected plant, insect, and soil samples from the desert. We gently touched “cactus pokies” (Anna and Weston, 4), “spikes” (Caroline and Zoey, 4), and “pointy stuff” (Caiden, 4) while learning the proper name of cactus spines and their functions.

In the spring, our desert came to life with the March rains. We planned to use this time of new life to explore our identity as caretakers of the earth.

Renovating Our Butterfly Garden

Spring’s promise of new life and new hope in our Sonoran Desert opened up a fresh and exciting project: reclaiming and recreating our Creation School butterfly garden which, unfortunately, was left unkempt due to on-site building construction (see Figure 8). This renovation became a community project for our pre-k classes to meld the uniqueness of our region, their understandings and connections their desert environment, and their cultural identities.

The importance of our butterfly garden grows out of our respect for and appreciation of the American Indian tribes around us. Few regions of the country can match Arizona’s wealth of Indigenous history and culture. The Tohono O’odham and Pascua Yaqui Tribes are located near Phoenix and Tucson. The importance of holding onto their unique tribal cultural identities revolves around connections to Earth and each other. These tribes have thrived for thousands of years living on a landscape that receives only a few inches of rain per year. We and our students have much to learn from them about being caretakers of the earth.

Deeply embedded into the heritage and culture of the Tohono O’odhams are the ceremonial rituals, such as rain dancing and the Butterfly Dance. The Butterfly Dance is celebrated because of the migration of the various colorful butterflies that dot the beautiful Sonoran Desert during the spring (McGivney, 2018).

Through the art of storytelling, American Indian traditions have been shared and passed on from one generation to the next. Hip Hip Hooray, It’s Monsoon Day! (Rivera-Ashford & Johnsen, 2007), speaks to sharing traditions through storytelling. Nana’s Remedies/Los Remedios De Mi Nana (Rivera-Ashford & Miguel, 2002) describes a grandmother sharing remedies with her granddaughter, using native medicinal plants. Sing Down the Rain (Moreillon & Chiago, 1997) shares the importance of summer rains to Tohono O’odhams for their crops. As teachers, we had not realized that oral traditions and the stories of the nations living within the Sonoran Desert were aspects of culture and global literature. Ray and Prisca Martens, through our Studying Studio helped us, as Vail, Arizonans, to understand more deeply the interwoven tapestry of our Southwest culture.

Unfortunately, due to COVID-19, what we had originally planned as a child-inspired/teacher-supported butterfly garden and water harvesting projects changed course over-night in March. Instead, they became an exercise in stretching our imaginations from reality into creating a “virtual” butterfly garden—to be planted later and our water harvesting exploration sometime in the future. The unexpected blessing was that our “whole-child” focused project now became a “whole-family” labor of love!

With distance learning over Zoom as our teaching tool to connect with our families, teachers introduced and explained our project. Together, the pre-k teachers brainstormed activities and ways to include family participation in this project at home. We encouraged parents to research which plants attract butterflies and which desert animals are best suited to co-exist in our butterfly garden.

Our new project began with a Zoom online introduction of the life cycle of plants and families taking sensory nature walks through their neighborhoods. We encouraged families to share photos, videos, and their children’s drawings recounting their experiences. Parents also shared their own vegetable and flower gardens. Through those adventures, we discovered which native plants and special colors invite butterflies to visit and linger among the flowers in our gardens.

To introduce the butterfly garden project to students, we recorded a video on the school campus at the site, showing the areas that we hoped to revitalize. As part of the video, we read My Colors, My World (Gonzalez, 2007). The story shares the many colors the young protagonist Maya finds in her home environment, like the beautiful butterfly, and the cheery orange marigolds.

During our Zoom call, we asked students to devise a “plan” for their butterfly gardens to share with their classmates during our next Zoom meetings. Our conversation also included questions like, “What would you plant? What animals should live here?”

Noel (age 4) said, “Crystals and stepping stones. Don’t forget a bird feeder. My Grammy has one to give the school.”

William (age 5), “Tall and small flowers would be nice.”

CJ (age 4), “Penstemon and fairy garden.”

Corinne (age 4), “Small turtles and rabbits…and a horse.”

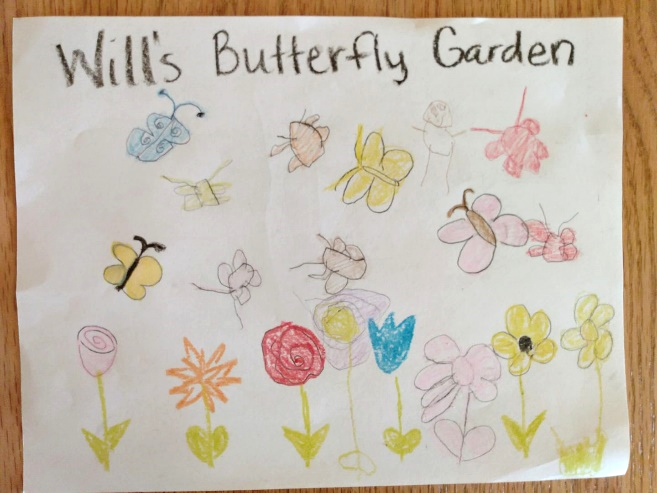

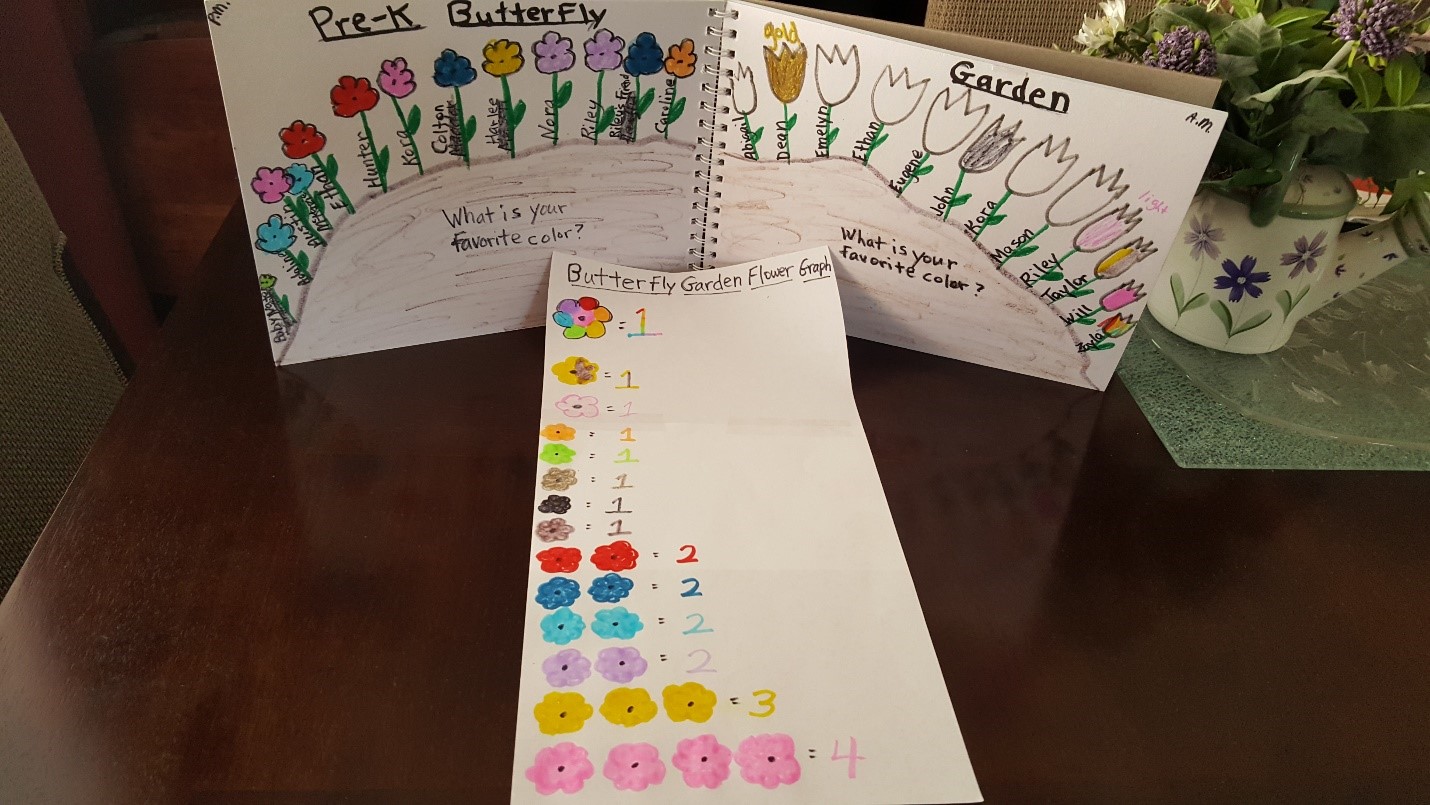

The next week during our Zoom meetings, teachers provided a webbing activity inquiring about each child’s favorite color that might attract butterflies. Children also shared their sketches with their ideas for a butterfly garden. These included a variety of flowers that ranged in colors from bright red to hot pink to shiny gold to one with rainbow hues! Will’s sketch is found in Figure 9.

During the Zoom meeting, as children shared their favorite colors, teachers created a graph of the flowers. We plan to use this graph when our virtual sketch becomes a real butterfly garden in the future (see Figure 10)!

Figure 10: Sketch and graph of students’ favorite colors for flowers in our future butterfly garden.

While we were not able to complete and renovate our butterfly garden this year, we look forward to using the children’s plans and ideas for it in the future. Fulfilling our identity as caretakers of the earth will begin in August while the monsoon rains are still fresh on the ground. Along with our study of the Sonoran Desert as a natural backdrop—providing magnificent vistas—our newly re-designed, child-inspired beautiful Creation School Butterfly Garden should exist in perfect harmony!

Final Reflections

Although the school year did not end as we had planned, we had some important realizations:

-

1. Young children learn best when experiences are tangible. They gain a sense of who they are by touching, smelling, tasting, hearing, and seeing. Our students used tangible experiences to tell their stories about our Sonoran Desert. Telling their desert stories helped them to think, organize their experiences, and learn (Corapi & Short, 2015).

2. Literature that speaks from a different time (like stories from Indigenous peoples) and the culture within our environment gave students a sense of their identities in place and time and being part of something greater than themselves.

3. Even in times of uncertainty, the human spirit can engage in beautiful things. Having some control over one’s environment (like planting seeds and watching them grow and re-creating a butterfly garden) can bring peace and advocacy.

4. One thing that doesn’t change is that we are all God’s children.

We created, we wrote, we narrated, we authored, we published, and through art and literature our identities as Creation School students, Vail, Arizonans, Sonoran Desert dwellers, and children of an awesome God were connected. We look forward to living our stories together again.

References

Corapi, S., & Short, K. G. (2015). Exploring international and intercultural understanding through global literature. Research Report, Web publication, Longview Foundation. http://wowlit.org/Documents/InterculturalUnderstanding.pdf

McGivney, A. (2018, November). Indigenous Arizona. Arizona Highways.

Children’s Literature References

Bash, B. (1989). Desert Giant: The World of the Saguaro Cactus. San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club.

Fredericks, A., & Spengler, K. (2011). Desert Night Desert Day. Tucson, AZ: Rio Chico.

Gonzalez, M. C. (2007). My Colors, My World. San Francisco, CA: Children’s Book Press.

Guiberson, B., & Lloyd, M. (1993). Cactus Hotel. New York: Square Fish.

Moreillon, J., & Chiago, M. (1997). Sing Down the Rain. Walnut, CA: Kiva.

National Geographic Society. (1987). Creatures of the Desert World. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society.

Rivera-Ashford, R.C., & Johnsen, R. (2007). Hip Hip Horray, It’s Monsoon Day! Tucson, AZ: Arizona Sonora Desert Museum Press.

Rivera-Ashford, R.C., & Miguel, E.S. (2002). My Nana’s Remedies/Los Remedios De Mi Nana. Tucson, AZ: Arizona Sonora Desert Museum Press.

Ward, J., & Rangner, M. (2003). The Seed and the Giant Saguaro. Flagstaff, AZ: Rising Moon.

Jane Metzger is the Inclusion teacher at Creation School, Vail, Arizona.

Jennifer Hook is the Director of Creation School, Vail, Arizona, and also teaches, most recently Pre-Kindergarten.

Vanessa Ruiz is a teacher at Creation School in Pre-Kindergarten or Early Learner classrooms.

© 2020 by Jane Metzger, Jennifer Hook, and Vanessa Ruiz

WOW Stories, Volume VIII, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work Jane Metzger, Jennifer Hook, and Vanessa Ruiz at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/volume-viii-issue-1/5/.

WOW stories: connections from the classroom

ISSN 2577-0551