Developing Understandings of Culture for Young Readers, Writers, and Artists through Global Literature

Prisca Martens and Ray Martens

Our goal as a global literacy community is to create a global curriculum in our school context to facilitate the development of young children’s intercultural understandings. We believe that young children can move toward a “stance of openness to multiple ways of thinking and being in the world and to differences as resources for our shared humanity and responsibility in working together to create a better and more just world” (Short, 2016, p. 10).

We organized our curriculum around a global framework (Short, 2006), creating experiences with global literature around the cultural identities of both students and children from global cultures, along with ways to act to help the world locally and beyond. Specifically, through readings, discussions, and experiences, we hoped to enrich and deepen students’ understandings of themselves as complex cultural beings; their respect for cultural perspectives and ways of living different than their own; their desire to learn about others and the world; and, their concern for issues in the world and will to make the world a better place.

An additional intent was to provide art and writing experiences that invited students to create their own meanings multimodally. Learning the language of art and integrating expressions of meanings in art with meanings in written language, we would challenge students’ imaginations and creativity and expand their abilities to compose meaning (e.g., Arizpe & Styles, 2003; Eisner, 2002; Martens & Martens, 2018; Martens, Martens, Doyle, Loomis, Fuhrman, Stout, & Soper, 2018).

Our School Context

Creation School is a Lutheran school located in Vail, Arizona, southeast of Tucson near the Rincon Mountains in the heart of the Sonoran Desert. According to the 2010 census, Vail is 69.76% non-Latinx White, 3.27% Black or African American, .85% American Indian, 2.44% Asian, .15% Pacific Islander, 4.98% other races, and 4.1% mixed race. People of Hispanic or Latinx origin made up 19.43% of the population.

The school, which has just completed its seventh year, has classes for students in preschool (beginning at age two), pre-kindergarten, kindergarten, and first grade. It provides a Christ-centered environment that nurtures children’s faith, strengthens families, and invites children to explore and discover their world through rich learning experiences. The outdoor classroom space includes chickens that children help raise, a butterfly garden, and a natural playscape (i.e., tires, crates, boards, natural elements), all of which extend students’ opportunities to inquire about their world, learn, and grow.

Our Vail Global Literacy Community included nine teachers: Vanessa Hoang, Cassi Sutherland, Nicole Martinez, Amanda Ortega, Jane Metzger, Vanessa Ruiz, Christy Reller, Lacey Elisea, and Jennifer Hook (also the school Director). In total these teachers taught about 50 students. We, Prisca and Ray, facilitated our literacy community. Most of the teachers had worked together for several years but we were new to the school. The school was about 50% Latinx heritage and 50% European American and Asian/other groups. A few teachers and students spoke Spanish, but English was the primary language used.

In the past, Creation School did not have a formal curriculum. Teachers used Bible stories as the base and designed lessons in other areas by drawing on the Arizona Early Learning Standards. Children’s literature was primarily used for read-alouds. In 2019-2020 our Worlds of Words Global Literacy Communities Grant opened possibilities for developing curriculum using global literature. Since this literature depicts cultures, regions, and people from other countries, it provided opportunities to build on understandings and highlight appreciations of diversity in our world that were already integral to the Christian/Lutheran beliefs in the school (Freeman, Lehman, & Scharer, 2007).

It was an exciting and rich year of learning and growing. When school closed for COVID-19 in March, we shifted to online learning with students through Zoom meetings. While these meetings were good, they did not provide the opportunities to do all that we intended through the end of the year.

Our Vail Global Literacy Community

Our literacy community met every few weeks throughout the year. In our meetings we discussed professional readings on global literature, intercultural understanding, and meaning-making in writing and art. Our readings included Exploring International and Intercultural Understanding Through Global Literature (Short & Corapi, 2015); “Engaging Young Children With Global Literature” (Acevedo, Pangle, Kleker, & Short, 2017); and, In Pictures and In Words: Teaching the Qualities of Good Writing Through Illustration Study (Ray, 2010). In each meeting we also shared happenings in classrooms and samples of students’ work; planned for the coming weeks; discussed problems/issues that arose; and, generated ideas to use in our classrooms.

Our Work in the Classrooms

We (Prisca and Ray) were at school three mornings a week to visit classrooms, due to time and schedules, primarily for pre-kindergarten (pre-k) and kindergarten/first grade (K/1). We developed a Storying Studio (Martens & Martens, 2018; Martens et al., 2018), where we read and discussed global literature, examined how the artist created meaning in the art, and provided experiences that encouraged students to reflect on the story, their learning, and/or the art. Over the year, our major foci were understanding and knowing ourselves as cultural beings; knowing, appreciating, and respecting the cultural identity of others (specifically, Mexican culture); and, composing personal meanings/stories through writing and art.

Identity: Knowing Ourselves

Our focus on identity and self-awareness invited students to think about and realize what makes them unique cultural beings, which is critical to accepting and valuing others (Banks, 2004). The books we read considered such aspects of identity as family, emotions, confidence, fears, and standing up for yourself and for others. Since particular geographical regions influence our cultures and personal perspectives (Corapi & Short, 2015), we also included a focus on the Sonoran Desert. We knew this would deepen students’ understandings of the unique area in which they lived and how it influenced them and their ways of living, thinking, and being in the world.

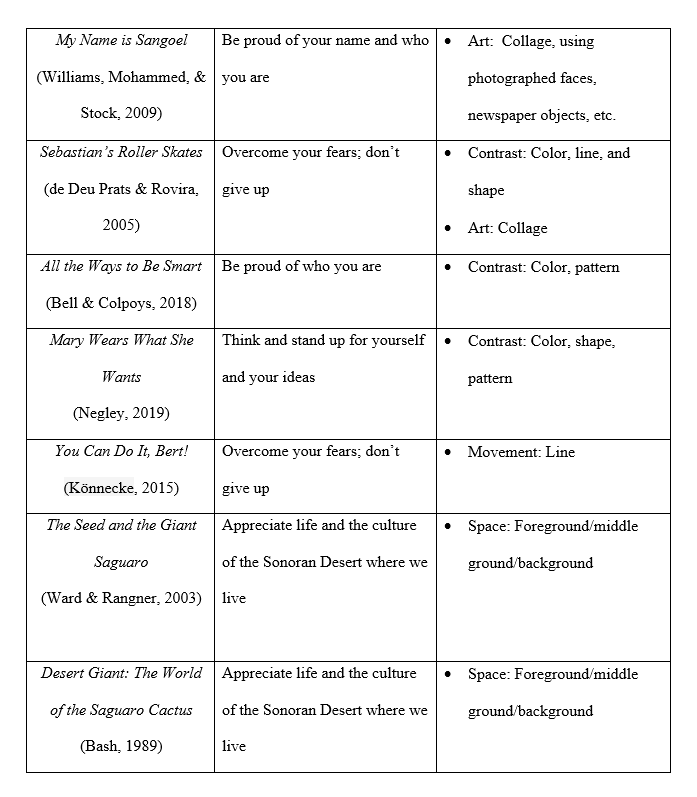

Figure 1 is a sampling of the books we read and art concepts we examined in the illustrations that artists used to convey meaning. With each book we read, students had opportunities to reflect and share their thinking and connections orally and in writing (journals or on other paper through writing and/or art). Through this focus on personal cultural identities students began to realize they have personal cultural perspectives and understand and appreciate that others also have cultural perspectives (Short & Thomas, 2011).

Cross-Cultural Study of Mexico: Knowing Others

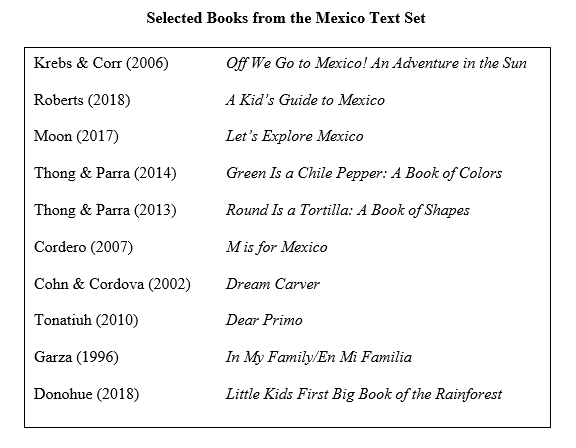

An important aspect of cultural identity and intercultural understandings is seeing ourselves as part of the world community (Banks, 2011). To further develop an appreciation of others we moved to a cross-cultural study of Mexico. We chose Mexico because of our proximity to it and the heritage and traditions some students shared with that culture. The Sonoran Desert’s extension into Mexico made a nice transition. The Mexico study was an opportunity to explore the culture and country more deeply, including language, geography (i.e., desert, beach, mountains, rainforest), native peoples/history, customs/traditions, families, beliefs, etc. A sampling of books we read is found in Figure 2.

The pre-k students usually documented important information we read and discussed that they wanted to remember in their Mexico journals. Sometimes, though, they recorded information on other paper, as they did for the plants and animals in the different layers of Mexico’s rainforest (see Figure 3).

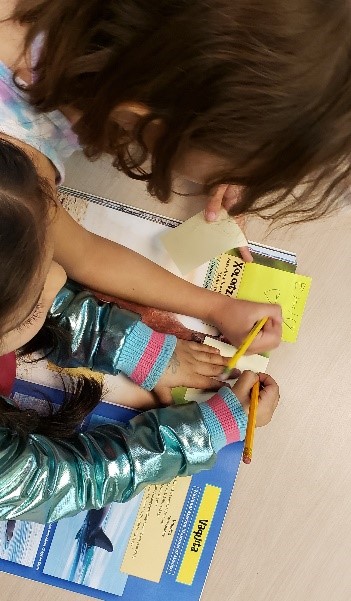

In K/1 students also used sticky notes to document information they thought was important (see Figure 4). They shared these notes in class discussions and placed them with other notes in their journals for future reference.

Our study of Mexico deepened students’ understandings of culture and helped them realize that “their cultural perspectives were only one of many ways to view and live in the world” (Short & Thomas, 2011, p. 156).

Storying Studio: Making Meaning by Composing Through Story

In Storying Studio we celebrated stories, both in literature we read related to identity, Mexico, or other stories, as well as students’ stories/reflections about themselves, their lives, and their responses to read-aloud books. We also explored diverse ways of making meaning through art and written language. Students learned the language of art (“Art Smart” terms) and how to think and compose as artists. As authors and artists, they learned to seamlessly weave together their meanings in two different symbolic systems (i.e., written language, art). Sometimes students’ stories were on separate sheets of paper, sometimes in journals or sketchbooks, and sometimes in books they created.

Students in kindergarten and first grade composed numerous stories on a range of student-selected topics/themes. To plan and organize their stories, they created storyboards and/or story dummies before composing their final stories (see Figure 5). Several of these stories were typed and published more formally.

Through experiences in Storying Studio students learned they have voices that are valued and important stories to tell and they identified themselves as readers, writers, and artists. Their stories evidenced their thinking, problem solving, decision making, and creativity (Martens et al., 2018).

An Invitation into Classrooms

In the vignettes that follow, we invite you into the classrooms as teachers share details of how they developed curriculum with global literature. The vignettes particularly highlight how students came to understand their identities and who we are, appreciate other cultures, and compose their own stories through writing and art.

- In “Learning About Identity in Kindergarten/First Grade through a Global Literature Lens,” Lacey Elisea and Christy Reller describe how they guided kindergartners and first graders in an exploration of their own identities and the identities of those in Mexico to strengthen the development of their intercultural understandings.

- In “Identity through Global Literature: Pre-Kindergarteners Learn About Themselves in the Sonoran Desert,” Jane Metzger, Jennifer Hook, and Vanessa Ruiz explain how they used learning experiences in the Sonoran Desert to help pre-k students not only appreciate where they lived but also deepen their understandings of themselves in their environment.

- In her vignette “Preschoolers Write Their First Stories through Art,” Cassandra Sutherland shares how, through discussions of characters in literature, she helped two-to-four-year-old students realize they have voices and stories and to tell their stories through art.

- In “Chinese Lunar New Year: A Celebration of Culture,” Vanessa Hoang details how she integrated a Chinese Lunar New Year’s celebration into the curriculum for Early Learners (two and three year olds) to help them understand the traditions and ways of life in another culture. She also includes how pre-kindergarten and kindergarten/first grade classrooms celebrated.

The 2019-2020 school year was one of learning and growing for all of us. We hope that our vignettes provide a taste of our excitement and offer insights into ways to develop students’ understandings of culture, themselves, and others through global literature.

References

Acevedo, M., Pangle, L., Kleker, D., & Short, K. (2017). Engaging young children with global literature. The Dragon Lode, 35(2), 17-26.

Arizpe, E., & Styles, M. (2003). Children reading pictures: Interpreting visual texts. New York, NY: RoutledgeFalmer.

Banks, J. (2004). Teaching for social justice, diversity, and citizenship in a global world. The Educational Forum, 68, 296-305.

Banks, J. (2011). Educating citizens in diverse societies. Intercultural Education, 22(4), 243-251.

Corapi, S., & Short, K. G. (2015). Exploring international and intercultural understanding through global literature. Research Report, Web publication, Longview Foundation. http://wowlit.org/Documents/InterculturalUnderstanding.pdf

Eisner, E. (2002). The arts and the creation of mind. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Freeman, E., Lehman, B., & Scharer, P. (2007). The challenges and opportunities of international literature. In N. Hadaway and M. McKenna (Eds.), Breaking boundaries with global literature: Celebrating diversity in K-12 Classrooms (pp. 33-51). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Martens, P., & Martens, R. (2018). Enhancing experiences with global picturebooks by learning the language of art. WOW Stories, VI(1). https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/wow-stories-volume-vi-issue-1/3/

Martens, P., Martens, R., Doyle, M., Loomis, J., Fuhrman, L., Stout, R., & Soper, E. (2018). Painting writing, writing painting: Thinking, “seeing,” and problem-solving through story. The Reading Teacher, 71(6), 669-679.

Ray, K.W. (2010). In pictures and in words: Teaching the qualities of good writing through illustration study. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Short, K. (2016). A curriculum that is intercultural. In K. Short, D. Day, and J. Schroeder (Eds.), Teaching globally: Reading the world through literature (pp. 3-24). Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Short, K., & Thomas, L. (2011). Developing intercultural understandings through global children’s literature. In R. Meyer and K. Whitmore (Eds.), Reclaiming reading: Teachers, students, and researchers regaining spaces for thinking and action (pp. 149-162). New York: Routledge.

Prisca Martens is Professor Emerita, Towson University, Towson, Maryland. She is retired and living in Vail, Arizona.

Ray Martens is Professor Emeritus, Towson University, Towson, Maryland. He is retired and living in Vail, Arizona.

© 2020 by Prisca Martens and Ray Martens

WOW Stories, Volume VIII, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work by Prisca Martens and Ray Martens at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/volume-viii-issue-1/3/.

WOW stories: connections from the classroom

ISSN 2577-0551