Download as PDF

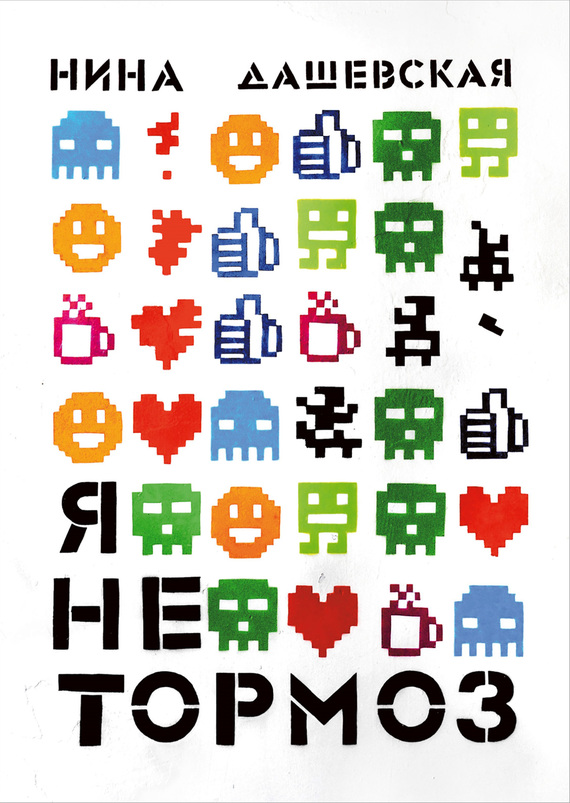

I Am Not a Dunce

I Am Not a Dunce

Written by Nina Dashevskaya

Cover by Vlada Myakonkina

Samokat, 2016, 160 pp.

ISBN: 978-5-91759-470-5

Book available only in Russian

Ignat never sits still. He needs to move. On a scooter, his regular means of transportation, on rollerblades, his favorite, on a skate board, his newest achievement, or just on his own two feet, Ignat moves speedily, glides freely, slides downhill, hurries down the escalator on the subway. Ignat is thirteen and, in many ways, an ordinary schoolboy. He lives with parents and younger brother, but his father is an anthropologist and is always somewhere in the field while his mother, a stage designer in a big theater, often works in the evenings. Ignat takes care of his brother, Leva, and while Ignat likes the responsibility, Leva, a kindergartener, is not always that easy to manage.

Ignat believes that he is quite ordinary, and apart from being fast, he does not believe he has many other good qualities. He knows a lot, but finds it difficult to bring his thoughts into order. He even suspects that something might be wrong with him. He wonders if he might be sick or abnormal because his thoughts also run with high speed.

“I, sometimes, have so many thoughts in my head, and they all jump around as if they are in a boiling pot under the lid and try to escape; they knock against the walls – boom! boom! They move in all directions; they are all about different things and on different tracks, like there is a Brownian motion in my dome. Like my head will crack, pop up! At such times, the best is to put on my rollerblades, left, right, dash, dash, and the thoughts form a long line, stretched and well-proportioned” (pp. 25-26).

Ignat is out of sync with those within his world, and thus believes he is “a lone wolf” who is not like others. Running through life with full speed, he abruptly stops when someone needs his help–an elderly person who falls on the street, a crying girl in the park, or even his own mom who relies on him and assures him that there is nothing wrong with him. In addition, Ignat loves to read and writes poetry, which are often solitary activities. His dreams include learning to play the trumpet and bringing Moscow to life with his imagination.

A lovely book about a boy and his beloved neighborhood and city, this is also a book about Moscow, about city streets, sidewalks, parks, and the embankments of the Moscow River. Ignat loves his city, and he feels it with his feet as he travels though it every day. Eventually, Ignat learns how to balance his fast pace with moments of stillness and reflection—and the wonder of looking through the city’s wondrous windows.

The constant movement within this book pairs well with Man Booker Prize laureate David Grossman’s The Zigzag Kid (1994) and Someone to Run With (2000). The sense of difference Ignat feels over his sensitive nature would fit well with Ballad of the Broken Nose (2016) by Arne Svingen and Kari Dickson.

Nina Dashevskaya lives in Moscow; she is a musician and a violinist at the orchestra of the Moscow State Opera and Ballet Theater for Youth. She has published six books for children and young readers and received several prestigious Russian book prizes for her writing for teens. Music is always a crucial part of her writing.

Olga Bukhina, Russian Translator, New York City

WOW Review, Volume X, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/review/x-1/