From Ideas to Implementation: The Process of Creating Activities for Story Explorations

Marlene Flores

“This is so much better than regular reading! I wish we had more time to do these activities. I love working with craft stuff. Making my mini me was fun, then I could pretend to be the giant with my mini me model.” – Bernadett, Grade 4

“I love this type of stuff, because it really makes me think.” – Logan, Grade 4

Bernadett and Logan participate in Story Explorations, an Out-of-School Time Program that challenges their thinking while stimulating their creativity. Based on these quotes, it’s clear they enjoy reading new stories and working on projects that extend their thinking about each story. In this article, readers learn more about the Story Explorations, an Out-of-School Time Program offered to public schools located in southern New Mexico.

Story Explorations

Story Explorations is a program offered twice each academic year that engages students in grades 4, 5, and 6 in literacy activities designed around a thematic text set. The explorations are supported by STEM activities with an emphasis on six areas of language arts: reading, writing, speaking, listening, viewing, and visually representing (NCTE, 1996). These explorations help students improve their proficiencies in language arts. The aim is that these skills transfer into their regular school day learning and beyond.

Foundational to Story Explorations are high quality, culturally and linguistically relevant picturebooks (See Galleries 1 and 2). Students explore each picturebook by connecting hands-on activities that pique their curiosity and foster their creative thinking while building their comprehension strategies. Various genres are explored in this program such as fairytales and their variants, poetry, and folklore.

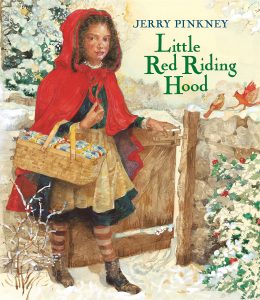

- Little Red Riding Hood by Jerry Pinkney, 2007, Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, 9780316013550.

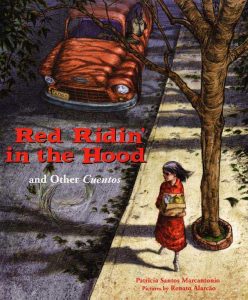

- Red Ridin’ in the Hood and Other Cuentos by Patricia Santos Marcantonio and Renato Alcarãu (illustrator), 2005, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 9780374362416.

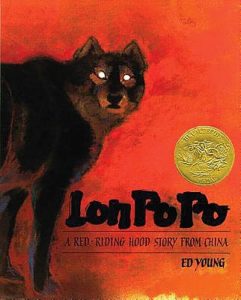

- Lon Po Po: A Red Riding Hood Story from China by Ed Young, 1996, Puffin Books, 9780698113824.

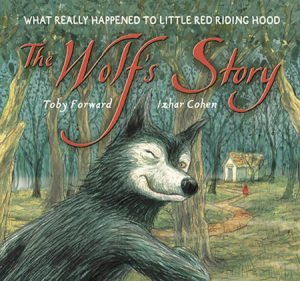

- The Wolf’s Story written by Toby Forward and Izhar Cohen (illustrator), 2006, Candlewick, 9780763627850.

Gallery 1. Picturebooks for Fall Story Explorations: Red Ridin’ In the Hood

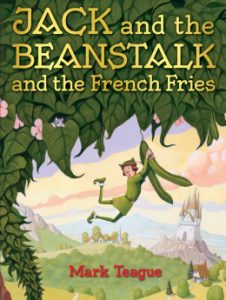

- Jack and the Beanstalk and the French Fries by Mark Teague, 2017, Scholastic Inc., 9780545914314.

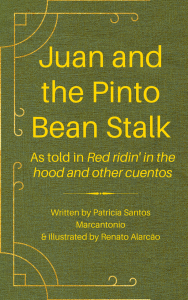

- Juan and the Pinto Bean Stalk from Red Ridin’ in the Hood and Other Cuentos by Patricia Santos Marcantonio and Renato Alcarãu (illustrator), 2005, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 9780374362416.

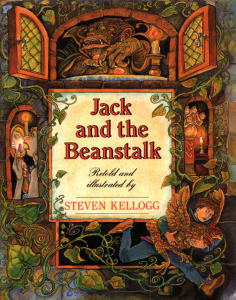

- Jack and the Beanstalk by Steven Kellogg, 1997, HarperCollins, 9780688152819.

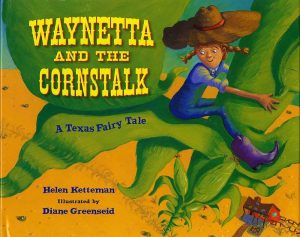

- Waynetta and the Cornstalk: A Texas Fairy Tale by Helen Ketteman and Diane Greenseid (illustrator), 2007, Albert Whitman & Company, 9780807586884.

Gallery 2. Picturebooks for Spring Story Explorations: Juan and the Pinto Bean Stalk

Story Explorations is a program offered by the STEM Outreach Center at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces, New Mexico, U.S. The STEM Outreach Center provides high-quality, innovative Out-of-School Time Programs to the communities of southern New Mexico. The mission of the Center is to build a strong framework that supports STEM education for under-represented students in area school districts. The STEM Center currently works in seven districts with over 400 teachers to provide programming to over 5,000 students.

The creation of Story Explorations stemmed from a need for a literacy program for intermediate grade levels. At one time, only STEM programs were offered to intermediate students. Additionally, instructors expressed a need for students to engage with books outside of their regular school day to explore, engage, and pique the students’ interest.

To do this, I and my colleague, Mary Fahrenbruck, explored stories that felt welcoming and relatable to intermediate students. We decided to focus on a fairytale theme for each exploration. Our first Story Exploration is titled Red Ridin’ in the Hood and the second is titled Juan and the Pinto Bean Stalk. Both short stories are part of a collection found in Red Ridin’ In the Hood and Other Cuentos written by Patricia Santos Marcantonio and illustrated by Renato Alarcão (2005). Red Ridin’ In the Hood is a fractured fairytale based on the classic Red Riding Hood story.

In Red Ridin’ in the Hood (Marcantonio, 2005), Roja must make her way through the city to her sick Abuelita’s apartment. Roja encounters Lobo Chavez hopping down the street in his low rider car. After Roja refuses a ride from Lobo Chavez, he races to Abuelita’s apartment building where he plans to impersonate Abuelita. Lobo Chavez’s plans are foiled when the police arrest him for planning to eat people and for impersonating Abuelita. The story ends with Roja and Abuelita driving off in Lobo Chavez’s low rider.

Juan and the Pinto Bean Stalk (Marcantonio, 2005) is a fractured fairytale based on the classic Jack and the Beanstalk story. In Juan and the Pinto Bean Stalk, Juan is unmoved by his mother’s wishes of a better future for him. Juan skips school to go to the beach and hangs out at the local 7-11 convenience store, eating microwave burritos. One day, Juan’s mother instructs him to sell their old, beat up car, Old Vaca. Juan sets off and meets a wheezing old man who trades Juan a handful of pinto beans for Old Vaca. This story follows the traditional plotline of an angry mother who throws the beans out the window where they grow into a beanstalk. Juan climbs the beanstalk, encounters a giant, steals the giant’s treasures, chops down the beanstalk, and lives happily ever after.

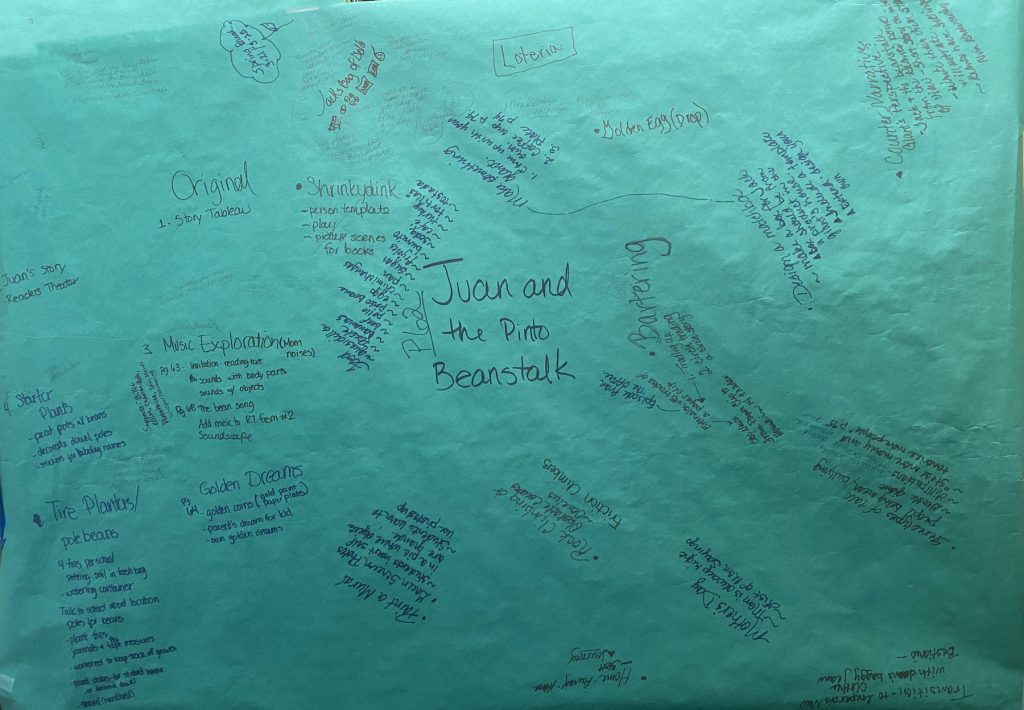

To begin developing each story exploration, Mary and I created a story map. We made a web of ideas for explorations that we thought intermediate grade students would enjoy (See Figure 1). This process allowed us to record all ideas, regardless of limitations.

Figure 1. Brainstorming Map

The next step was to select explorations that met our criteria:

- Time length of each session. Explorations need to fit into a 90-minute session. More involved explorations can be divided into two or three sessions if needed.

- Number of activities. Activities need to fit within the timeline of a 30-session program.

- Feasibility of materials. Each exploration needs to fit within the program budget constraints.

- Transportability of materials. Materials need to be able to be transported to school sites by instructors. All materials must fit into a vehicle.

- Academically and developmentally appropriate. Explorations need to align with student’s academic and developmental milestones.

- Seamless alignment to the picturebook. Explorations need to connect to the stories in obvious ways.

Our next step was to put the explorations in order of implementation. Then the fun began! We developed each exploration. For more complex explorations, we ordered the materials and experimented with them (See Figure 2). We wanted to make sure the explorations could be successfully implemented as planned.

Figure 2. Marlene Experiments with Materials

The next step was to compose each exploration using a template for uniformity that included relevant information for teachers. The template included background information about the story and about the activity planned, the steps for implementing the plan, the materials needed, and an activity to extend the activity into the students’ homes.

Finally, we advertised Story Explorations to teachers at participating school sites. During our first Story Exploration, 15 teachers agreed to implement Red Ridin’ In the Hood (Marcantonio, 2005). For our second Story Exploration, 16 teachers agreed to implement Juan and the Pinto Bean Stalk (Marcantonio, 2005). We were both surprised and excited by the success of Story Explorations.

In this issue of WOW Stories, three teachers who agreed to implement Story Explorations have written vignettes about their experiences. They discuss how students related to the stories and activities, and how these explorations have brought joy to their teaching experience.

What We Learned from Creating Story Explorations

Story Explorations began as an idea that, with trials and errors, developed into a successful Out-of-School Time Program. Much of the success stems from our reflections about what we have learned from interacting with teachers and students.

Fairytales are timeless. We learned that fairytales still hold their magic with intermediate grade students. Students still enjoy listening to and learning with traditional fairytales as well as fairytale variants. As Geraldine, a fifth-grade Story Explorations participant, stated, “I’ve had fun learning new stories and doing the projects. We don’t get to do projects all the time during regular school.”

Not all ideas are good ideas. We learned while brainstorming ideas for activities in Story Explorations that some activities had limitations. Initially, we believed the sky was the limit. For example, we wanted to give teachers car tires to make planters for an activity in the Juan and the Pinto Bean Stalk Story Exploration. We discarded this idea because of the transportability of materials criteria.

Too many activities. We learned that the number of activities we created were too numerous to fit into a 30-session program. We kept the most pertinent activities. This allowed for a deeper exploration of the stories we had selected.

Teachers will adapt. We learned that teachers felt confident in adapting the activities to meet the needs of the students. For example, Carmen Rodriguez, one of the program instructors and authors in this issue of WOW Stories, adapted one of the activities to resemble a popular television game show illustrating how she relates the activity to students.

Programs relate to school and home. We learned that we could design activities that students could take home to engage their families. Families responded positively, resulting in deeper home-school relationships.

We were grateful for the opportunity to follow up with teachers and students through observations, surveys, and focus group meetings. Their feedback provided us with helpful tips that we plan to use to create equally successful programs in the future.

Moving Forward

The success of the fairytale themed Story Explorations has motivated us to create two new story explorations with a mythological theme. Based on what we learned about our process and the ways that students engage with the explorations, we anticipate that more teachers will want to implement these Out-of-School Time Programs and even more students will want to participate.

Marlene Flores is a Program Specialist at the STEM Outreach Center at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces, New Mexico, USA.

Children’s Literature Cited

Forward, T. (2006). The wolf’s story (illus. by I. Cohen). Walker.

Kellogg, S. (1997). Jack and the beanstalk. HarperCollins.

Ketteman, H. (2007). Waynetta and the cornstalk: A Texas fairy tale (illus. by D. Greenseid). Whitman.

Marcantonio, P. S. (2005). Red ridin’ in the hood and other cuentos (illus. by R. Alcarãu). Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Pinkney, J. (2007). Little Red Riding Hood. Little, Brown.

Teague, M. (2017). Jack and the beanstalk and the french fries. Orchard.

Young, E. (1996). Lon Po Po: A Red Riding Hood story from China. Puffin.

References

National Council of Teachers of English (1996). Standards for the English language arts. International Reading Association and National Council of Teachers of English.

Authors retain copyright over the vignettes published in this journal and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under the following Creative Commons License:

WOW Stories, Volume X, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on work by Marlene Flores at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/wow-stories-volume-x-issue-2/3.

WOW stories: connections from the classroom

ISSN 2577-0551