Creating Our Cultural Identity Quilt: Using Literature to Explore Who We Are

by Amy Gaddes

Starting from the end seems like the right approach to tell this story. Beginning at the end, during the last session of the school year with a small group of graduating sixth grade English Language Learners (ELLs) is the place I need to begin because it was at this point that my students joined me in a conversation that not only exemplified the work and trust that we have built as a community of learners, but in many ways also signified a new beginning in our understanding of ourselves as cultural beings. The journey as a community of learners and the texts that helped us frame this conversation will be revealed as I unfold the nuances of what brought us to our final session together.

Before I share this conversation, I will contextualize these learners. In this group of students, I have 8 sixth grade ELLs that can be categorized, based on New York State’s Proficiency standards, the following way: 2 beginners, 2 intermediate, and 4 advanced students. Two of the advanced students have been in my English as a Second Language class since first grade. The others in the class have been in the United States from 1-3 years. Each student is, therefore, in various phases of language learning, acculturation, and language and cultural loss.

I approached our final unit for the year with a backwards design (Wiggins & McTighe, 1998) to culminate in the creation of a cultural identity quilt. By the last class, we had read several texts that framed our conversations. These texts were chosen from various genres with the central idea of examining the fluid nature of our identity. Each student had individually contributed two handcrafted quilt squares, and participated in a variety of healthy conversations about what ‘cultural identity’ means to each of us. I want to emphasize, before I retell this pivotal discussion, that the trust and practice in openly sharing has come together over many years for this group. Although some of the students entered this space as newcomers a year or two ago, the rules of engagement had been well practiced. Even with the linguistic challenges newcomers brought to this forum, they could perceive the safe nature of the room for all who came to our learning circle. This allowed us to take all we learned together and respectfully share ideas and experiences, and question how things work in the world.

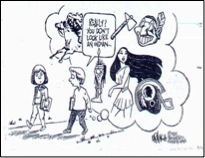

To help the students consider the idea of their own cultural identity, I framed the unit around learning about the Native American experience in this country. At our previous session, I distributed an article written by a Native American university student about mascots for sports teams that degraded her heritage. At the end of this reading, I included some images of these mascots and a cartoon for their consideration. In a dialogue bubble, one school-aged child says to another: “But you don’t look Indian.” There is a thought bubble depicting various images in the speaker’s head of Pocahontas, cowboys and Indians, and sports mascots. Armed with this image, weeks of reading and exploring our own cultural identities, and a safe space, my students entered a rich class discussion. (All names are pseudonyms.)

I asked the students to study the cartoon and offer an explanation of what the characters might be thinking. Manal described how the boy in the cartoon might have constructed his ideas of what Native Americans look like from watching television. Prior to this whole class conversation, Manal, who is from Pakistan and has been in the United States for one year had spoken to me about her concerns of people’s misconceptions about Muslim people. She glanced around the circle of her peers and sought eye contact with me as she expanded on her interpretation of the cartoon. She explained to the class that she was Muslim, and how, in her experience, many people seem to get their ideas about Muslims from watching television. She shared that although she agreed that some Muslims have done terrible things to other people and other countries, not all Muslims should be categorized in that way. Manal paused and looked at each of her classmates before asking if anything she had ever done seemed mean.

At this point, Jejomar, a Filipino who emigrated 5 years ago, asked what a Muslim was. I took the opportunity to explain that being Muslim is a religion, like Catholicism or Judaism. Jejomar pondered this and stated that he did not know what religion he was. Manal added that at her home she and her sister cover their hair because it would be improper, according to her religion, to be around her father and brother-in-law with their hair exposed. Listening to all this, Jejomar raised his hand and asked, “I have another question. If you are Jewish and you went into a Catholic church or where Manal goes, would you be arrested?” While this conversation took twists and turns I had not anticipated, I carefully explained that in the United States, which was founded on religious freedom, something like that would not happen. I went on to have the students consider that their own families may have immigrated to the United States for the very same types of freedoms.

One of my quieter students, Guillermo, who emigrated from Mexico one year ago, asked what freedom meant. With so many classroom discussions with English Language Learners, I have to be acutely aware of everyone’s linguistic understandings. Guillermo’s question reminded me that I might have let the personal or emotional aspect of this book discussion go beyond the language capabilities of some of my newer learners. I offered a broad definition of freedom as the ability to go wherever you want, say whatever you want, and, in the case of religion, worship wherever you may want.

Another student from Mexico, Estaban, whose family emigrated 4 years ago, had been absorbing this dialogue with careful scrutiny. He raised his hand and stated that immigrants are not free to go where they want to in the United States. He went on to say that there were politicians who didn’t want to give immigrants health care or citizenship. Each turn of this discussion challenged my role in the classroom as a caring adult and a culturally sensitive teacher. I asked Estaban if he had conversations like this with his family and he explained to us that he carefully watched and thought about the news. Manal summed up the emotions in the room and asked if we could use another word other than ‘immigrant’ because it “makes us feel bad.”

Our talk, which started with an invitation to explore the cultural identity of Native Americans based on a cartoon image, took us in many challenging directions.

How did we get to such candid and open conversation? What tools did these twelve-year-old students have to so poignantly and deeply explore a cartoon image depicting another culture and relate it to their own lives in such an adult manner? Kathy Short (2009) helps us understand that literature can provide “a window on a culture, but also encourage insights into students’ cultural identities.” (p. 6).

This unit started about one month before when each student was asked to respond to the prompt, “Are Native Americans alive today,” on an index card. Six of the eight children said, “No”. Two of the students thought that perhaps there were some ‘children of children of children’ who may still be alive today. One stated, “No, I live in New York and I never saw a Native American.” After watching a video from the Discovery Channel showing Native American children living on a reservation in today’s world, the students were both shocked and intrigued. This set the stage for me to introduce the unit about cultural identity. We talked about their pre-conceived notions of what a Native American may be like and, using the video, the students modified their preliminary ideas. I distributed Post-it notes and asked the students to write down what they wondered about Native Americans at this point. Two examples of their responses include the following statements.

I wonder if Native Americans have to pay taxes?”

I wonder how America got to be so beautiful again after all the conflicts that it had a long time ago.

To continue my exploration about the universal theme of cultural identity, I turned to a text set of picture books about a person’s name and the role that names play as a foundation of our own identity. I read aloud My Name is Sangoel, by Karen Lynn Williams and Khadra Mohammed (2009).

To continue my exploration about the universal theme of cultural identity, I turned to a text set of picture books about a person’s name and the role that names play as a foundation of our own identity. I read aloud My Name is Sangoel, by Karen Lynn Williams and Khadra Mohammed (2009).

Partners then chose from a text set of picture books.

|

Calato Laineiz, R. (2009). Rene has two last names. Houston, TX: Arte Publico. Henkes, K. (2008). Chrysanthemum. New York: Mulburry Books. Recorvits, H. (2003). My name is Yoon. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Williams, K. L. & Mohammed, K. (2009). My name is Sangoel. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdman’s. |

Figure 1: Text set of picture books.

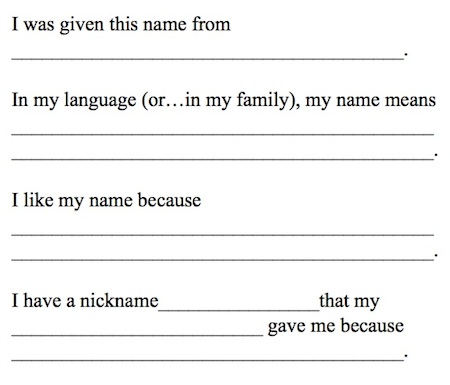

Each student went home and interviewed their family about the origin and meaning of their own names.

Figure 2: Names: A Home Interview

I was particularly moved by the response from my student who emigrated from Pakistan. She wrote: “ I was given this name from my mother. In my language, my name means half of the moon. It represents who I am. It is my identity. It makes me special because everyone’s name is different. But your name is one of a kind.”

Manal’s comments were written after her sharing about her mother’s death. She was able to make this connection and take this risk in part because of the support offered by the text and the protagonist’s experience with his own name’s origin. Sangoel explains in the beginning of the story that he and his mother and sister had to escape the Sudan after his father was killed. Manal never articulated the nature of her mother’s passing, but she appears to connect great pride to her ‘special’ name given to her by her late mother.

Having these preliminary explorations about cultural identities, we were ready to begin our read aloud of Fatty Legs (Poiak-Fenton, 2010). Fatty Legs is the true story of Margaret Poiak-Fenton, who coauthored this book with her sister-in-law, Christy Jordan-Fenton.

Margaret tells her story of being ‘plucked’ from her family at age 8 in her native village north of the Artic Circle and sent to a boarding school run by Caucasian Catholic nuns and priests. The narrator painfully describes how systematic attempts were made to strip her of her language and cultural practices. They cut her braids, and as she cries she remembers that her father said, “You will always be Inuit…you will always be Olemaun” (her Inuit name). My students made a rich connection to our previous text, My Name is Sangoel (Williams & Mohammed, 2009), where Sangoel’s elder tells him, “You will always be Sangoel…always be Dinka, even after you go to the United States.”

Signaled by my students’ strong connections to these texts, I had my opportunity to introduce our quilt-making project. I offered each student two quilt squares. One was white where the students were invited to draw their country’s flag; the other was a color of their choice where they were invited to create an image that showed their cultural identity.

The students were not sure how to start. I returned to our anchor text, Fatty Legs, with the characteristics Margaret felt lost to her: her braids, her native name, her mother’s cooking, her language, her clothing and even the climate and vegetation from her northern village. I offered the students time to consider their own aspects of their identity. According to Nieto (1999), “culture is dynamic, active, changing, always on the move” (p. 49). We revisited how Margaret’s sense of self changed after her two-year stay at the Catholic school. We explored the “hybrid” nature of their own cultural worlds as their lives have unfolded in the United States. I offered access to the Internet for ideas and images that might confirm their current thinking about their identities. Jejomar quickly got to work on his quilt square. He drew Michael Jordan’s jersey and a pair of basketball sneakers. Following suit, Guillermo drew a soccer ball and Messi’s jersey. The students would not let me miss the fluidity of their own cultures and what needed to go on the quilt. I spoke with them about how much they were able to teach me. They explained to me that this is who they are. This allowed me to give them the space to demonstrate this on the quilt. In a very touching way, it also allowed them to re-visit where they came from and where they see themselves going.

I hadn’t planned on reading the sequel to Fatty Legs (Poiak-Fenton, 2010). The school year was coming to a close and I had just a few more sessions with these students. When I brought in the sequel, A Stranger At Home (Poiak-Fenton, 2011), we explored the title and cover. Some students commented on how it has felt when they returned to their home countries and the conflict they experienced when interacting with relatives who have not left their homeland. My students “already recognized the complexity of culture within their own lives” (Short, 2009, p.5). This helped them to bring insights as they critically discussed Margaret’s experience when returning home.

I hadn’t planned on reading the sequel to Fatty Legs (Poiak-Fenton, 2010). The school year was coming to a close and I had just a few more sessions with these students. When I brought in the sequel, A Stranger At Home (Poiak-Fenton, 2011), we explored the title and cover. Some students commented on how it has felt when they returned to their home countries and the conflict they experienced when interacting with relatives who have not left their homeland. My students “already recognized the complexity of culture within their own lives” (Short, 2009, p.5). This helped them to bring insights as they critically discussed Margaret’s experience when returning home.

Because of state testing, a week or two went by before we met again. This gave me time to sew the quilt and have it on display for the students’ return to my class. With the quilt as the backdrop, our discussion, described earlier, emerged.

There was a lot for me to take away from this experience. First, it is not enough to create a text set and gather anchor texts on a theme you want to explore. You must be patient and carefully place each text into students’ hands when they are ready to explore their deeper content. I could have gone from one text to the next, lace in a few writing assignments to see what the students were thinking, and ended it there. I felt enormously rewarded for my willingness to wait, watch, and listen, and let them tell me when and how they could use the texts to support their thinking.

My use of these global texts spoke to my international students in ways I could never have imagined. Beautiful and painful experiences were shared, and stirring questions were asked. My students grew up during these conversations. Likewise, I learned that my own agenda about culture is just that. I needed my students to show me what the quilt needed to look like. I needed them to guide me, as I opened the door for them to look at what culture meant to each of them. Having the texts by our sides allowed each of us to do this with a bit more confidence and candor.

References:

Nieto, S. (1999). The light in their eyes: Creating multicultural learning communities. New York: Teacher College Press.

Short, K. G. (2009). Critically reading the world: Building intercultural understanding through literature. Bookbird, 2, 1-10.

Wiggins, G. &McTighe, J. (1998). Understanding by design. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

References for Children’s Literature

Calato Laineiz, R. (2009). Rene has two last names. Houston, TX: Arte Publico.

Henkes, K. (2008). Chrysanthemum. New York: Mulburry Books.

Poiak-Fenton, M. &, Jordan-Fenton, C. (2010). Fatty legs. Toronto: Annick.

Poiak-Fenton, M. &, Jordan-Fenton, C. (2011). A stranger at home. Toronto: Annick.

Recorvits, H. (2003). My name is Yoon. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Williams, K. L. & Mohammed, K. (2009). My name is Sangoel. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdman’s.

Amy Gaddes is an ESL teacher of a K-6 population of diverse English Language Learners. Many of her students, living in a community just outside the border of a borough of New York City, are recently arrived immigrants predominately from Haiti, the Philippines, and Central and South America.

WOW Stories, Volume IV, Issue 6 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at .

This is wonderful!

What a powerfully arming experience this was!

Bravo Maggie Burns- what a meaningful lesson these boys learned!