by Yoo Kyung Sung, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque and Junko Sakoi, Tucson Unified School District, Tucson

Queen Elizabeth II, the UK’s longest-serving monarch, recently passed away at age 96, after reigning for 70 years. Fourteen countries continue to maintain the monarch as their head of state after gaining independence, despite the collapse of the British Empire in the last century. The death of Queen Elizabeth II could readily accelerate the push by former U.K. colonies to ditch the British crown amid heightened anti-colonial sentiments in the remaining Commonwealth realms (Halb, 2022).

Former UK colonies’ anti-colonial sentiment made us think of colonial histories and facts that are not current hot topics discussed within the global community. Global knowledge of physical outcomes of colonization history is now often romanticized as the beautiful substance of architects, food, festivals, tourism, etc. European countries’ colonial histories in Africa and South America remain aesthetically appreciated based on the historical background of languages, hybrid cultures, diverse ethnicities and educational contexts. Lost are critical perspectives on the colonizers’ past and the colonial indigenous cultures. This leads Junko and I to realize how colonial history among Asian countries is often simplified as Asian history; not knowing who colonized whom in Asia is often a common misperception.

This month, Junko and I explore Korean picturebooks translated and published in Japan to analyze colonization patterns in Korea. In 1910, Korea was annexed by the Empire of Japan after years of war, intimidation and political machinations; Japan ruled Korea until 1945, the end of World War II. Until then, Korea was one of Japan’s colonies. During the Korean War that followed, South Korea established strong ties to the U.K.

This month, Junko and I explore Korean picturebooks translated and published in Japan to analyze colonization patterns in Korea. In 1910, Korea was annexed by the Empire of Japan after years of war, intimidation and political machinations; Japan ruled Korea until 1945, the end of World War II. Until then, Korea was one of Japan’s colonies. During the Korean War that followed, South Korea established strong ties to the U.K.

Ten to 15 years ago, Junko and I noticed how picturebook representations of South Korea tend to have a particular postcolonial pattern–rural landscapes, folklore and traditional Korean holidays. Stories of contemporary Korea and Korean children’s childhood were not widely available as a traditional focus of Korean cultures and landscapes. Post-coloniality in those picturebooks was noticeable. Yet recently published books during the last 5 years challenge such textual experiences of international Korean children’s books in Japan. Korean picturebooks published recently in Japan explore broader topics of realistic fiction, contemporary childhood perspectives and celebrity authors.

A Look Back on Translated Korean Picturebooks

The following six Korean picturebooks translated into Japanese were published in Japan between the 1990s and early 2000s. Each book includes the Japanese publication date.

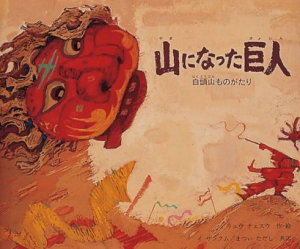

A Giant Who Became a Mountain by Jae Soo Ryu (1990). This text is a traditional creation story of the Baektu Mountain, located on the border of North Korea and China. The story focuses on a giant becoming a mountain who watches over the Korean peninsula.

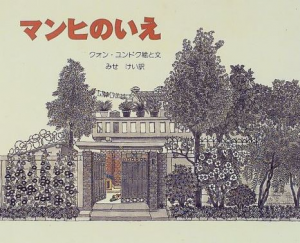

Mahni’s House by Jae Soo Ryu (1998). Mahni and his parents are busy packing for a move to their grandparents’ house, an old style Korean home in a city. Illustrations portray the old days of residential areas in cities like Seoul. Today, houses like Mahni’s have been removed as a part of city planning. Instead, old style homes are replaced with high-rise building filled with condominiums. Additionally, many old style houses are transformed into cafes and restaurants, forming entire streets filled with businesses for tourists.

Mahni’s House by Jae Soo Ryu (1998). Mahni and his parents are busy packing for a move to their grandparents’ house, an old style Korean home in a city. Illustrations portray the old days of residential areas in cities like Seoul. Today, houses like Mahni’s have been removed as a part of city planning. Instead, old style homes are replaced with high-rise building filled with condominiums. Additionally, many old style houses are transformed into cafes and restaurants, forming entire streets filled with businesses for tourists.

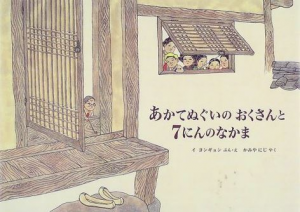

Needlework Ladies and Their Seven Fairies by Young Kyung Lee (1999). This Young Kyung Lee’s folk art style picture book tells the story of seven needlework fairies who start to talk and compete over their roles. They struggle over who serves the most important role and has the best talent for completing the lady’s needlework. The house, appearance of the sleeping needle lady and seven fairies are depicted through Chosun dynasty outfits and house styles. Perhaps this Chosun style is the most familiar image of Korean society in the past to mainstream audiences in Japan.

Needlework Ladies and Their Seven Fairies by Young Kyung Lee (1999). This Young Kyung Lee’s folk art style picture book tells the story of seven needlework fairies who start to talk and compete over their roles. They struggle over who serves the most important role and has the best talent for completing the lady’s needlework. The house, appearance of the sleeping needle lady and seven fairies are depicted through Chosun dynasty outfits and house styles. Perhaps this Chosun style is the most familiar image of Korean society in the past to mainstream audiences in Japan.

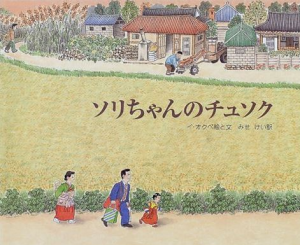

Sori’s Chusuk by Uk-bae Lee (2000). A girl visits her parents’ hometown in the countryside to celebrate Chusuk, the Korean Thanksgiving (Harvest Festival). She sees her grandparents expressing thanks to ancestors. The landscape of the town reminds readers of their annual holiday trip to grandparents’ places.

Sori’s Chusuk by Uk-bae Lee (2000). A girl visits her parents’ hometown in the countryside to celebrate Chusuk, the Korean Thanksgiving (Harvest Festival). She sees her grandparents expressing thanks to ancestors. The landscape of the town reminds readers of their annual holiday trip to grandparents’ places.

Busy Days by Goo Byung Yoon (2000)[1]. The story is set in a Korean village during the autumn season. A boy and his family are busy getting ready for winter. They gather crops, harvest rice, and make preserved foods such as wintering Kimchi and dried persimmons. The house, seen in an antiquated setting, may mislead readers to perceive the Korean country landscape as being older than typically seen today.

Busy Days by Goo Byung Yoon (2000)[1]. The story is set in a Korean village during the autumn season. A boy and his family are busy getting ready for winter. They gather crops, harvest rice, and make preserved foods such as wintering Kimchi and dried persimmons. The house, seen in an antiquated setting, may mislead readers to perceive the Korean country landscape as being older than typically seen today.

A Cow and Dokkaebi by Sang Lee (2004). Dokkaebi are nature deities. They can interact with humans using the extraordinary powers and abilities they possess. One day a boy happens to meet an injured Dokkaebi whose tail is bitten by a dog and he decides to take care of the deity.

A Cow and Dokkaebi by Sang Lee (2004). Dokkaebi are nature deities. They can interact with humans using the extraordinary powers and abilities they possess. One day a boy happens to meet an injured Dokkaebi whose tail is bitten by a dog and he decides to take care of the deity.

These six books published at the close of the 20th century maintain a postcolonial pattern through a focus on spirituality, rural landscapes, folklore and traditional Korean holidays.

Currents Trends in Translated South Korean Picturebooks

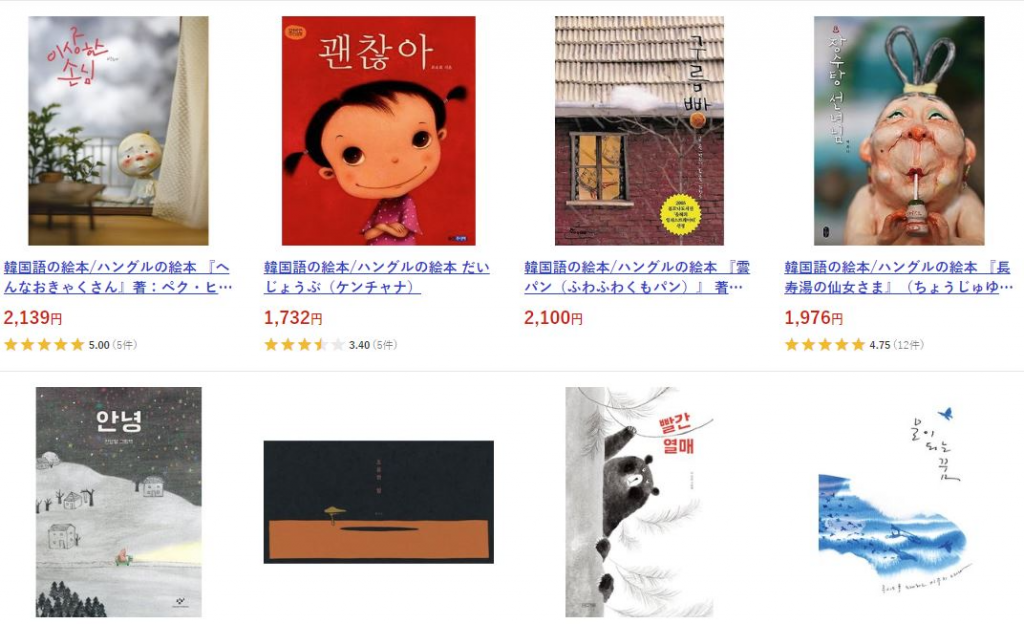

Recent trends in Korean picturebooks that earned attention and gained popularity reflect authors’ prominence and recognition of authors’ and illustrators’ art styles. Postcolonial literary experiences seem to meet Japanese readers’ conceptual representations of Korea (e.g., countryside, folklore, holidays, etc.). An additional new trend is that not only translated books but also non-translated Korean original picturebooks are available in Japan. EhonNavi, the largest online showcase of Japanese children’s books, lists 488 Korean original picturebooks (see Image 1). They also showcase 385 international children’s books translated into the Korean language and make these books available in Japan (see Image 2). Perhaps it reflects a growing number of Japanese people who are interested in K-Pop and Korean culture and language.

Image 1: Non-translated Korean picturebooks available in Japan (EhonNavi, 2022)

Image 2: International children’s books translated into Korean language and available in Japan (EhonNavi, 2022)[2]

We feel encouraged by these recent Korean texts translated for the Japanese children’s book market, thereby encouraging former Japanese colonizers to embrace a more contemporary lens on Korea life, beyond a post-colonial perspective. In our second post, we will discuss Korean picturebook authors whose books and international status influence the market of translated picturebooks in Japan.

Reference

Harb, A. (2022) Queen’s death accelerates ex-colonies’ push to ditch UK crown. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/9/14/queens-death-accelerates-ex-colonies-push-to-ditch-uk-crown

WOW Currents is a space to talk about forward-thinking trends in global children’s and adolescent literature and how we use that literature with students. “Currents” is a play on words for trends and timeliness and the way we talk about social media. We encourage you to participate by leaving comments and sharing this post with your peers. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit its archival stream.

- Themes: Junko Sakoi, Yoo Kyung Sung

- Descriptors: Books & Resources, Debates & Trends, WOW Currents