By María V. Acevedo, Texas A&M University-San Antonio, San Antonio, TX

With Rebecca Ballenger, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ

I read out loud All Around Us, by Xelena Gonzalez, illustrated by Adriana García, to a class of undergraduate students. When I read, “We eat what we’ve grown-crunchy lettuce, sweet carrots and spicy chiles,” one of my students said, “I love your Spanish accent.” Chiles is the only Spanish word in this picturebook and it is not italicized. The student’s comment made me think of picturebooks that highlight non-English words in one way or another and the implications of this practice to fictional characters and readers.

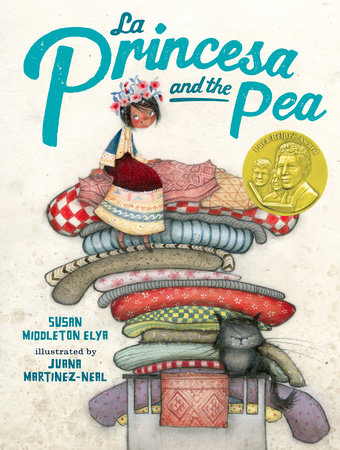

This post focuses on picturebooks because many times this format is approached from a didactical stance that values picturebooks for their ability to be used as teaching tools. Also, when it comes to picturebooks, the text is altered in numerous ways (I assume) to appeal the younger audience. For example, “She placed el guisante in the bed for their guest.” In La Princesa and the Pea, by Susan Middleton Elya, illustrated by Juana Martinez-Neal, the Spanish text changes font and color, adding to the text’s subjects: Spanish language-Vocabulary. Now, this is a visually engaging book to teach Spanish.

I argue that the practice of highlighting non-English words in English picturebooks can be problematic. However, I will provide questions, rather than statements to encourage conversation:

Molly Bang argues that the corner of the page is the corner of the world. In other words, what happens in the pages constitutes the world of the story. That being said, does “Five beach palapas” (from One Is a PIÑATA, by Roseanne Greenfield Thong, illustrated by John Parra) sound real? Would it sound authentic to bilingual characters and bilingual readers? Do bilingual individuals raise their voices or insert exaggerated non-verbal communication to convey meaning when they code-switch? I don’t. And, I actually used the illustrations and my counting skills to infer palala because it is not part of Puerto Rican Spanish discourse.

If the text in the picturebooks is distinguishing Spanish from English, then who is the intended audience of the books? Is it an English monolingual? If so, how does this practice position bilingual or multilingual characters and readers? As others, as different, as exotic, as excluded from what the text deems “normal”?

When literacy is about meaning, how does highlighting non-English words engage readers in using contextual cues from the written text and the illustrations to make meaning? Emphasizing non-English words can lead to underestimating readers’ literacy abilities, as well as to fail to expose readers to the wonders and complexities of languages. One common example: dime—is it “ten cents” or “tell me”? Readers need to be encouraged to figure it out. Is it “Ten cents me a story” or “Tell me story”? What if readers are encouraged to apply strategies for unknown words across languages? If children can identify nonsense words (DEIBELS Nonsense Word Fluency), they can indeed explore new words that are contextualized in the stories.

I would like to end this post by thinking about views on language(s). The practice of sorting words into languages can lead to viewing languages as static, fixed, changeless, which ignores the nature of languages as thinking and communicative tools, grounded in cultural practices and belief systems. It also contributes to a lack of awareness regarding the historical interconnectedness between languages and the role of languages in shaping individual and collective identities. This issue raises multiple questions, such as who decides what constitutes formal and informal language? What if formal schooling emphasizes pragmatics and metalinguistic awareness, rather than vocabulary? Vocabulary is important, but deep understanding of semantics is grounded in the social uses of language.

[WOW uses “picturebook” as one compound word rather than an adjective and noun to emphasize the relationship between the text and art in these books. You can’t tell the story without both the words and images. “Picturebook” indicates their equal importance.]

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit archival stream.

- Themes: Maria V. Acevedo, Rebecca Ballenger

- Descriptors: Debates & Trends, WOW Currents