Helping Young Students Think Conceptually: An Inquiry Study of Hunger and Power

by Jaquetta Alexander, First/Second Grade Teacher, Van Horne Elementary School

One of the consequences of shifting to an inquiry-based approach in my teaching has been a shift in how I plan curriculum. Instead of following a predetermined set of theme units and lesson plans, I look at larger chunks of time and am constantly involved in examining student thinking and questions in order to determine where we might go next in our learning. I still have a plan and a focus for our inquiry, but find that I need to spend time carefully examining student work, reflecting on my observations, rereading my teaching journal, and talking with colleagues to create that plan for curriculum.

Having explored a school-wide concept of power for the fall semester, I met with my colleague, Jennifer Griffith, to consider where this inquiry might go during the spring semester. Jennifer and I had worked together closely the previous year, but this year we were teaching a combination class of first and second graders, sixty students total. After reflecting over the fall semester, one tension stood out for us. Each year during the holidays our Student Council organizes a food drive for the Community Food Bank. We realized that our students were not making a meaningful connection to this effort. They did not get to see what happened to that food and where it went after they gathered it, and we had not offered them opportunities to understand the significance of this endeavor. The relationship between the students’ efforts to support the Community Food Bank and our inquiry into power sparked a realization that we could deepen their conceptual understanding of power by thinking broadly about the Power of Food.

Reflecting now on our work, I realize that the journey our students took prompted a real shift in understanding. Initially our students brought in canned food for the food drive during the fall because they were asked, but by the end of the spring semester, they brought in canned food because they understood the needs of families and identified with the reasons behind why we donate to the Community Food Bank. Short and Harste (1996) argue that inquiry should always begin with connections to the concept based on children’s life experiences before broadening understanding of the issue. Instead of starting our inquiry so far away from the children as had been done with the food drive, we wanted to start this time by having children think about food in their own lives and what it means to have tight times as a family. Because of the economic crisis in the U.S. and our community, we felt these were powerful points of connection for children.

Lisa Thomas, our Learning Lab teacher, started the process of thinking about food with our students. She read Burger Boy by Alan Durant (2005), a story about a boy who eats so many burgers that he turned into one! After a short literature discussion, Lisa asked the students to think about diet and food, and the power that food has in their lives, continually asking students to ponder the concept of power. Each student was given a piece of paper to show what they would eat if they had the power to choose their food. On the other side of the paper, they drew what their parents would choose for them to eat if their parents had all the power. This engagement proved to be helpful in setting the foundation to help students understand “The Power of Food.”

The next Learning Lab session provided students with a touchstone text. Lisa read Tight Times by Barbara Shook Hazen (1979), a book about a boy who wanted a dog, but his family couldn’t afford one because the father had lost his job. It was apparent from the literature discussion that our students made strong connections to this book.

Bailey: I have a connection because we sometimes go through tough times, but we always get through it.

Maria: My cousin doesn’t have much because her mom doesn’t have much because her dad doesn’t pay money.

Justin: My dad has hard times because he quit his job.

Ysabel: My mom has hard times because she quit her job. We don’t have many toys either.

Haley: Do you have a car?

Ysabel: No, it broke down.

Bailey: I have a connection to Ysabel because my mom quit her job, and I don’t get to see my dad much because he works from 4:00 in the morning to 5:00 at night. I miss my dad.

Nick: My mom, sister, dad and me had a tough time because we got a dog from the pound, and he got sick. He had to be put asleep.

Connor: I have a connection with Bailey because my dad works overtime now.

Maria: I have a connection with Connor because my dad has to work more to work on the planes.

Our discussion about tough times continued into our next Learning Lab session when Lisa asked the students, “What are tight times?” The students’ responses were:

• not much money

• not much food or money

• may not have houses

• may live in shelters

• no money to go to school, and can’t have dogs or cats

When asked to be more specific, “What are tight times when we’re talking about money?” Justin stated, “It’s like if you get some money and you want a game but you don’t have food. You should buy the food.” Justin continued to reflect, “It’s what you need, not what you want.” Dewey (1938) argues that the beginning of instruction shall be the experience learners already have; that this experience and the capacities that have been developed during its course provide the starting point for all further learning. At this point, it was clear that our students were making connections to issues related to tight times and that they were ready to build upon that knowledge. We decided to shift their thinking to explore the root causes of hunger so that they could build strong understandings of why people suffer from hunger and the different kinds of tight times that families might experience.

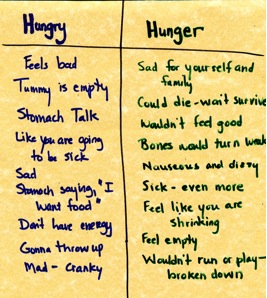

We talked together as a staff about the kinds of invitations we might offer students in order to engage them in productive learning that would encourage them to develop new understandings and take them beyond their life experiences. It was at this point that we introduced the students to the terms hungry, hunger, and famine in the Learning Lab. Every student had felt hungry, and so Lisa described hunger as a feeling you have when you’re hungry for a very, very long time. We asked the students to describe what hungry and hunger might feel like. They described hungry as feeling bad, feeling mad or cranky, and feeling like you are going to be sick. Hunger was described as a feeling of sadness for yourself and your family, an empty feeling, and a feeling that you are broken down. Lisa helped them grasp the term famine by describing that it was when thousands and thousands of people in an area experience hunger.

In the same Learning Lab session we hoped to push their thinking when we introduced the non-fiction book Feeding the World by Janine Amos (1993). This book gives examples of causes of hunger, such as drought and war. By using selected parts of this text we hoped to give the students information that would support their understandings of the causes of hunger and famine. This Learning Lab session was important because it pushed the students to think about things that were uncomfortable, things that they had not experienced before, and things that would be important to their understanding in later engagements.

Around this time, during a Study Group session, we explored a book by Stephanie Kempf (2005), Finding Solutions to Hunger: A Sourcebook for Middle and Upper School Teachers. After thoughtful discussions and careful consideration we decided to modify an engagement from this book so it would be appropriate for our elementary students. “Eating the Way the World Eats” allows students to experience firsthand how unfairly food is distributed in our world. Three different meals are prepared in advance -– each representing one of the three groups in the world: those who have more than their fair share of food, those who have just enough, and those who never get enough food to stay healthy. By sheer “luck of the draw” students are randomly assigned to one of these groups (Kempf, 2005). We held a school-wide banquet to simulate this activity. Our first and second graders attended the banquet with other students in grades three to five. Each student was given a ticket with a color that represented a percentage of the world’s population; yellow represented 60%, blue represented 15%, and red represented 25%. The students were simply told that they were going to eat the way the world eats. We delivered pizza, enough pizza to feed everyone present, to the blue group. There was excited chatter and a sense of anticipation in the air at that point. Then we delivered community bowls of beans and rice to the yellow tables. The yellow group was divided into ten tables of six students. Each table received a community bowl. The red group was given one community bowl for all 25 students, who were sitting on the floor. To simulate natural movement due to changes in circumstance we then moved several students from one group to another due to changing economic factors. We anticipated a mixed reaction from the students, and that is exactly what happened. It was important to us that the banquet not create anger or hostility within the groups. Our goal was to elicit thinking and further our students’ conceptual understanding of power, specifically food as connected to issues of power. Therefore, in the end, after everyone had the opportunity to experience how the world eats, each student got to eat pizza.

Jennifer and I were uncertain as to the significance of the banquet and how it affected our young students’ understandings, however, the conversation we had with our students immediately following the banquet helped to put aside some of our uncertainty. Students made a range of comments:

Jordan: I was happy when I walked in, but I got scared because there were a lot of people there.

Carah: When I got a ticket and sat down I got excited, but then I felt angry because we got beans and rice. I didn’t want beans and rice.

Reid: You should feel lucky you got pizza from us.

Abbey A.: We should be lucky and grateful that we even got food.

Abby G.: I think I disagree. When I came in and got a ticket I wondered what it was all about. Then I smelled the pizza and thought we were going to get it, then the blue table got it and I was mad.

Morgan: I felt sad for other people in Tucson because we live in the desert and there’s not much food in the desert. I feel sad for people who have to suffer. That’s lots of days to eat just beans and rice.

Carah: I’m heartbroken because the red group sounds so sad.

Morgan: In real life people actually suffer. Maybe the people who have lots of food could share.

Dewey (1938) suggests that we create environments that have the most potential for tension. Morgan’s comment was significant because we could sense that our students were experiencing tension over the fact that there are people in our world who do not have enough to eat. We perceived those tensions as opportunities to move our students beyond learning and into deep understanding. Now that our students were on the edge of knowing about the distribution of food and the power of food we were excited to expand our work into the classroom.

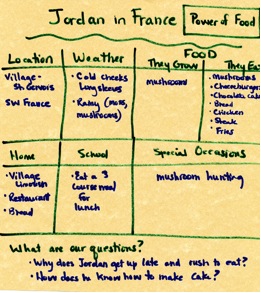

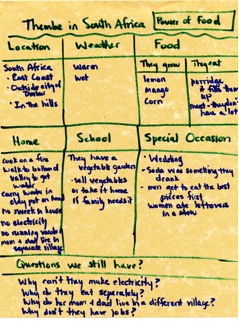

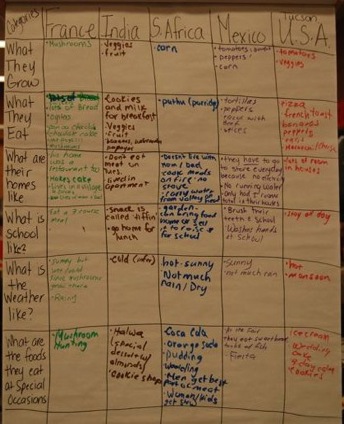

Jennifer and I wanted to offer a progression of experiences that would be appropriate to engage our students in productive learning. We hoped to enhance the work being done in the Learning Lab, in which Lisa was helping the students to understand root causes of hunger, such as poverty, economic failure and food distribution. Therefore, in the classroom we began exploring examples of children in other countries who have enough food to eat. At first this idea may seem odd since our goal was to help our students understand hunger, however, we knew that we needed to start with our students’ own life experiences, and since none of our students had experienced hunger or famine we wanted to start with having them examine the food they eat in families and how that differs for other families around the world. We relied heavily on Beatrice Hollyer’s book, Let’s Eat! What Children Eat Around the World (2003). This non-fiction text describes the daily lives of six children, each from a different country. We decided to chart what we were learning about the location, weather, food, home and school life, special occasions, and any questions that still lingered after reading a section of the book on a particular child. This book was very engaging because it allowed students to make connections to children from around the world who were their same age. The students engaged in many conversations related to how the children from the book lead lives that are both similar and different from their lives. We took several weeks to read, discuss, and chart our students’ understandings. Finally, we created a comparison chart so the students could think about their lives compared to the lives of the children in the book.

Because our students easily made connections to other children from around the world by exploring their daily lives, we were ready to shift their thinking so they could explore their tensions over the fact that there are people in the world who do not have enough food to eat. We discovered two non-fiction texts that were critical in helping our students understand that many children around the world do not have enough food to eat. These two books, through their text and powerful pictures, helped our students see what hunger and famine look like. As with Let’s Eat! What Children Eat around the World, we read Out of the Dump by Kristin Franklin and Nancy McGirr (1996), and The Lost Boys of Natinga: A School for Sudan’s Young Refugees by Judy Walgren (1998) over many days. Out of the Dump is a compilation of photographs taken by children living in the garbage dump in the center of Guatemala City. Accompanying each photograph is a piece of writing that describes the photograph, also written by the children living in the dump. The Lost Boys of Natinga: A School for Sudan’s Young Refugees discusses the lost boys arrival, the history of the lost boys, and their life at Natinga, including school, food, church, health, and recreation. Because the entire text was not appropriate and would have overwhelmed our young children, we used only the portions that would be of benefit to our students’ understanding of the power of food.

Even though both books were significant to student understanding, perhaps the most powerful engagements were the school visits from Amanda Morse of the Community Food Bank and Abraham Deng Ater, a lost boy from Natinga. The opportunity for the students to hear first-hand accounts of hunger solidified their understanding of the power of food. Amanda Morse first asked the students what they had already learned about food issues. Some of their responses were:

• when some people have food and others don’t

• sometimes you send so much food out of a country that you don’t have enough food in the country

• famine

• how food is transferred-transportation

• where food comes from

• what the difference is between hunger and hungry

• sometimes people don’t have enough money to pay for food

Amanda described the difference between food secure (safe access to food for a healthy life) and food insecure (don’t have food or safe access to food). She also described the purpose of the Community Food Bank and the populations that they serve. The students were surprised to learn that 40% of the people getting food from the food bank are kids! To end her program she stated that donating food is a short-term solution, but teaching people to plant their own gardens is a long-term solution. Our students immediately made the connection to our class garden. We had already planted a garden and were making all kinds of discoveries, such as which plants grow faster, how much water and sunlight is required, etc. Amanda’s presentation furthered our students’ understanding of the power of food.

Abraham Deng Ater described his journey from the Sudan to Ethiopia to Kenya and finally to the United States. He shared his experiences with having little or no food. He described how he felt and helped students grasp the difference between hungry and hunger, which had always seemed a difficult concept for them. We knew the students had made the connection when they began asking questions that were particular to the book that we had read about the lost boys, such as “Did you know anyone who ate poisonous leaves and died?” We had read about how children in Natinga had become so hungry that they would forage for leaves and would sometimes eat the wrong (poisonous) leaves and die.

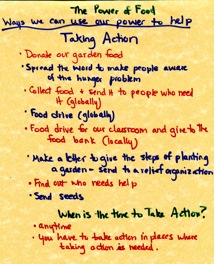

All of these engagements created a context through which students could conceptualize The Power of Food. Since we had based our journey on our students’ life experiences, they were able to build their understandings and add to them as the year progressed. Because Jennifer and I had worked closely the previous year, bringing together our first and second graders, we were able to give the students opportunities to take action in our community. This year’s second graders benefited from that knowledge of taking action. Roger Hart (1992) argues that, “Children need to be involved in meaningful projects with adults. It is unrealistic to expect them suddenly to become responsible, participating adult citizens at the age of 16, 18, or 21 without prior exposure to the skills and responsibilities involved” (p. 5). This kind of thinking pushes us as educators to constantly challenge our students to become better individuals. We also recognized that power is tied to action because it is the ability to influence an outcome. Our thinking was that kids need the opportunity to take action in order to understand power. Therefore, we did not impose our thinking onto students but thought with them and provided structures that challenged them to think more deeply about their understandings of the power of food. We asked them two guiding questions, “How can we use our power to help?” and “When is the time to take action?” Our students said that any time was the time to take action and that we had to take action in places where action was needed. It was obvious that our students were thinking both globally and locally when deciding how to use our power to help.

As this chart indicates, the students wanted to help by donating food from our garden, having a food drive, and spreading the word about hunger to make people more aware. The students decided that our first step had to be to find out who needs help. Ultimately our first and second graders decided to take action locally by collecting seeds, gardening tools, and food to deliver to the Community Food Bank when we visited for a field trip. Our students worked hard to create posters for the school and also to take home. Students even made posters for their parents to take to work! In the end we delivered 674 pounds of food along with packets of seeds to the Community Food Bank. I have always been particularly drawn to the work of Vivian Vasquez (2004), who has shown that even very young children are capable of creating change in their world and taking action on issues that are significant in their lives. In the last several years, I have made some of these same discoveries when working with young children. This year’s class was no different.

After having time to reflect and analyze the journey we took in understanding the power of food, I think the student engagements allowed a flow of experiences that enabled students to better understand the concept. By starting with the students’ life experiences, inviting students to reach out globally to create understandings, and then bringing the concept back to their own lives to take action, students gained a broad and deep understanding of the power of food. These experiences, in turn, provided me with new understandings about curriculum and helped me create a framework that will be beneficial to future planning because it is not specific to this one learning experience. This flow of experiences as a frame for curriuculum is one I can use to think about my planning in other areas of instruction. I gained a conceptual understanding of inquiry and curriculum, just as my students gained a conceptual understanding of power and hunger.

References

Amos, J. (1993). Feeding the world. Austin: Raintree Steck-Vaughn.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience & education. New York: Collier.

Durant, A. (2005). Burger boy. London: Andersen.

Franklin, K. & McGirr, N. (1996). Out of the dump. New York: Lothrop, Lee & Shepard.

Hart, R. (1992). Children’s participation: From tokenism to citizenship. Florence, Italy: UNICEF.

Hazen, B. (1979). Tight times. New York: Puffin.

Hollyer, B. (2003). Let’s eat! What children eat around the world. New York: Henry Holt.

Kempf, S. (2005). Finding solutions to hunger: a sourcebook for middle and upper school teachers. New York: World Hunger Year.

Short, K. & Harste, J. (1996). Creating classrooms for authors and inquirers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Vasquez, V. (2004). Negotiating critical literacies with young children. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Walgren, J. (1998). The lost boys of Natinga: A school for Sudan’s young refugees. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

(2001). From farm to table [film]. Wynnewood: Schlessinger Media.

WOW Stories, Volume I, Issue 3 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi3/.

One thought on “WOW Stories: Connections from the Classroom”

Comments are closed.