Getting Past the Social Drama to Engage Fifth Graders with Power

by Amy Edwards, Fifth Grade Teacher, Van Horne Elementary School

Our class began the year looking at the concept of power in the Learning Lab. The idea of power had come up the previous year as a strong connection for our kids and so we chose to explore it more deeply as our conceptual frame for the school year. The Learning Lab is a special place where our kids experience focused lessons around a big idea that is carried over into the classroom curriculum. The work is international in focus and inquiry based. Our goal is to teach about global issues through the world of books. Through story worlds students are invited to gain insights into how people live, feel, and think in their own culture as well as those of global cultures (Short, 2008). Teachers involved in the lab are also a part of an after school study group to explore themes, big ideas, and the wonderings of our students. We are joined each week by a University of Arizona researcher, Kathy Short, who is interested in how kids learn about interculturalism. Kathy collaborates with the teachers involved with the project and is an invaluable resource and an expert in international children’s literature. Lisa Thomas, our project specialist, facilitates the lab where our work is guided by the inquiry of students. Students are really pushed to think in new ways in the lab and it is a favorite part of their week.

Fifth graders are a special variety of elementary student. They feel deeply, exude confidence due to their being the oldest kids in school, and are often looked up to by their younger peers, even though there are moments when they revert to being little kids themselves. They know about power. They also have the art of being cool down pretty well out of constant concern about impressing their peers. When you think they are just about to make a breakthrough on thinking about ideas metaphorically or conceptually, they will act like they could care less. After all, they are fifth graders.

Reading and discussing literature in small groups is important because it allows students to position themselves differently in relation to peers, teacher, and text. In every literary practice there are social codes that are manipulated by both teacher and students (Lewis, 2001). Just as context shapes performance, ongoing performances continually shape and reshape classroom context. The meanings of social and interpretive competence are constantly co-constructed by the teacher and students resulting in expectations for appropriate action and interaction. Many times these negotiations for social position occur without teacher surveillance in peer groups. The set of norms within which students have learned to work in the lab often challenge their existing social positions by asking them to work and think deeply with each other. The students are expected to think critically, conceptually, and make connections. The social drama occurring with these kids, however, sometimes interfers with their willingness to engage in thinking with each other in our learning lab experiences.

Traditionally, reading is viewed as a set of psychological skills used to gain meaning from text, thus successful reading is a technical matter that results from skilled teaching and talented students. Recently, reading and writing have been defined differently, as social and cultural practices (Bloome & Katz, 1997). When people are involved in reading or writing, they are creating two sets of social relationships. The first social relationships being established are between themselves as readers and the authors of the books, and secondly among the people present in the reading event itself. According to Bloome and Katz, this second set of relationships is called participant social relationships. These social and cultural practices were interesting to watch with this group as they worked through conceptualizing power. Anyone who witnessed their literature circles and class discussions in the lab would unmistakably see these dynamics at work. Even though students made significant connections to the concept of power, it wasn’t until the end of the study that they were able to work beyond the social positions and roles created by themselves, their peers, and the adults. We noted that particular engagements allowed them to get beyond their participant social relationships into working as members of equal standing on a team because they were so engaged in thinking together about ideas.

In our first day in the Learning Lab, Lisa started our discussion by reminding students about our study of journey the previous year. She reminded them that we started off talking about journeys in the literal sense and then began to think more broadly and in symbolic ways. She talked about the importance of big ideas and that the understandings they developed through our study of journey helped us connect to broader concepts. This year, she explained, we wanted to think about power. She asked them to think about power in their lives, particularly about decisions they make in school and how those related to their lives. Students were clearly interested in thinking about these ideas.

Lisa started off by reading Big Plans (Shea, 2008) in which a boy who is in trouble at school is sitting in the corner after filling the chalkboard with “I will not….” sentences as punishment. He is angry about being in time out and makes plans to take over the world. “I have plans,” he says, “big plans.” The kids listened quietly, chuckling occasionally, and then responded to the book:

Robert: He wants more power in the class. He’s the “underkid” in the class.

Robbie: Everything he talks about is in the picture.

Kyra: It says in the story that the President is bossy.

Dakota: He is moving up. He starts out as the kid and then becomes powerful — the president.

Kyra: He is abusing his power. He orders Idaho to build. He demands Missouri to cheer up.

Dakota: He is powerless. He is imagining his power — demanding it. It’s like a dream.

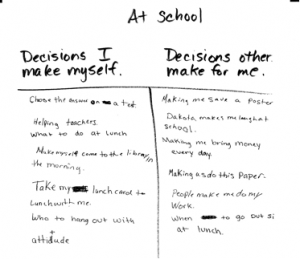

Lisa asked the students to think about how decisions are affected by power. In their small groups, they made a T-Chart about school. One side showed “Decisions I get to make” and on the other side “Decisions others make for me.” Their charts included a range of observations about power in school:

Decisions Others Make

• People tell you who to be friends with.

• We have to wait in computer lab for others, even when you know what to do.

• When to go outside at lunch.

• Who to be partners with.

• Schedule for the day.

• Don’t choose the books the school buys.

• Dress code.

• People make us do our work.

• The music we play in Band/Orchestra.

Decisions We Make Ourselves

• Taking care of ourselves.

• Who to hang out with-who to be friends with.

• What instrument we play in Band/Orchestra.

• Choose the books we read.

• What to wear.

• Answers on a test.

• Three choices for lunch.

• What to play on the playground.

In circulating around the groups as they were working, Alyssa and I had a conversation about power. She noticed that the things she had no control over were not always in the control of someone directly above her. She said that kids don’t always get to choose what they want to learn about. When I told her that I don’t always get to teach what I want, and that the Department of Education tells me what to teach, she made the connection that there is a hierarchy of power. When talking with Danielle’s group, an attitude of cynicism that was typical of fifth graders became apparent. They noticed that the choices they had available in many situations were limited. For instance, at lunch they could choose from either hot lunch or lunch express, but the choices were limited to only two things. They could choose to drink milk, but the flavors to choose from were determined by adults and limited to only three flavors. This cynical attitude became clear in their class discussion.

As students synthesize what they had charted, they came up with several big ideas about power. Lisa kept a large chart on the story floor to record their big ideas about power and added to it each week right before our class left the lab.

Jake L.: Some people have more power than others.

Robbie: Students do have some power.

Jake L: We have power in different ways, like the Olympics.

Danielle: Some do, some don’t, but we all try to have power.

Alexis: Some choose to have it. Some choose not to have it. Some don’t notice they have power. Some have it and don’t use it.

Jake L: I noticed power doesn’t always work. You don’t have to do something, as long as you’re willing to take the consequences. No one can make you do something.

Danielle: You can choose certain things but only from a selection that others have already chosen. You can choose a flavor of milk but can’t choose what flavors are offered. There’s a limited selection. Others choose for us.

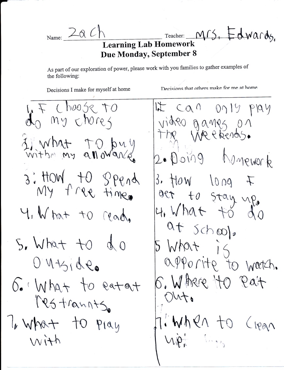

Students were asked to complete a homework assignment that involved a T-chart on the choices they get to make at home and the choices others make for them. They were asked to get their family’s point of view as well. As we left the lab, students made a connection between power and homework, pointing out that they have to do homework, but they can choose when to do it.

In the next lab session we reviewed our big ideas about power from the previous week and added their new observations about power based on their charting at home.

• Some people don’t know how to use power.

• Some people abuse power.

• Some people have power over others.

• Your parents are taking power from you if they don’t let you do something.

• Some people try to have power but can’t because of consequences.

• When it comes to power/decisions, no one can really MAKE you do anything.

• Everyone has at least a little power.

Lisa read an excerpt from Hey World, Here I Am (Little, 1986) titled “About Lovin,” a short story that demonstrated how some families show love. She wanted students to understand that families operate in different ways as a framework for sharing the homework. She told the students that all families work well most of the time and that all families have problems some of the time. She encouraged the students not to be afraid to share about the decisions made in their families and asked them not to judge others as they were sharing the homework about decisions at home. If people felt judged, they wouldn’t share and be honest.

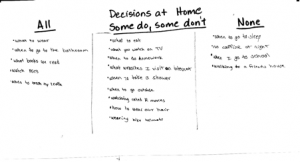

Students went to tables to share who made decisions about what things in their families and charted their responses. As they were discussing if everyone at the table agreed on who made particular decisions in their families, that decision went in the “All” category, but they had to come to a consensus. The same standards were applied to each category.

Decisions I get to make at Home

All Some do, some don’t None

As I went around the room I noticed decisions being added to the charts, including:

• When to practice instruments

• When to go to sleep

• Only child so have more choices

• The larger the group, the fewer the choices

• What to watch on TV

• When you get grounded

• If you get to take showers

• What to do after school

• When to go to bed

• Drink caffeine at night

• Watch PG-13 movies

• Choose position you sleep in

• When to get haircut

The kids did a great job of reporting without judging other family’s decisions. I was glad of Lisa’s warnings and encouragements to be open minded as I found myself silently comparing some of the decisions with those of my own in raising my family and reminding myself that everyone does things differently.

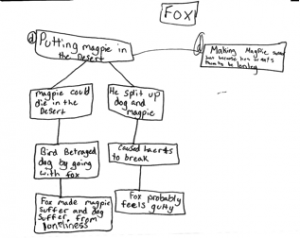

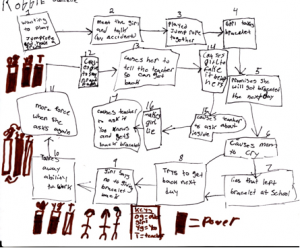

Jake’s comments about being willing to suffer the consequences led us to think about power and consequences for our next lesson. Lisa showed the students how to make a flow chart using the story of Dodsworth’s life from The Pink Refrigerator (Egan, 2007), which was a touchstone book from the previous year with our study of Journey. The students remembered the book well as it was one we revisited time and again. The flow chart showed each decision Dodsworth made and the consequences of that decision. After reading aloud Fox (Wild, 2001) and having a short discussion, students were asked to choose a character from Fox and examine a decision that character made in the story. They worked in pairs to make a flow chart of the consequences of that decision.

Students were really engaged with these flow charts. They put a “D” next to the box that showed the decision and then used arrows to show the consequences of that decision. AJ, Jorden, and Zach H. chose Fox and his decision to take Magpie to the desert. Some of the consequences were:

• Magpie would tell everyone if she survived and Fox would be suspected.

• Dog would go out looking for Magpie and dog could get lost, hurt, or dehydrated. Dog might think he was left by Magpie and be hesitant to make a new friend.

• Magpie would die. Dog would be sad.

Another group also focused on the same decision by Fox, but their flow chart reflected the consequences for Magpie rather than Dog.

Lisa asked students to bring these decisions together so that new ideas could be added to the class chart. Students added observations about power, choices, and consequences.

If someone has more power than you, you will probably do what they want, even if you don’t want to do what they ask. You might do it because you don’t want them to get mad at you.

We were reading novels about China in small groups in my classroom during this time period and I noticed students talking about who had power in the story. They noticed that certain characters held more power than others and that sometimes power shifted over the course of the story. It was exciting to see the kids make this connection between the Learning Lab and class.

We moved into a discussion about how power can shift over time in our next lab time. Lisa shared a story from her childhood in which she had to improve her math scores to stay on the Patrols. Power shifted as Lisa studied hard to do better on her timed math tests but then was accused of cheating by the teacher. Lisa’s mother talked to the teacher to verify that she had been studying at home to improve her scores and Lisa was allowed to continue on the Patrol squad. The students discussed the events and connections to power while Lisa created a flow chart focusing on power shifts.

Lisa read aloud Yoon and the Jade Bracelet (Recorvits, 2008) about Yoon, a recent immigrant from Korea. Yoon is given a beautiful jade bracelet by her mother and a new friend at school manipulates Yoon into letting her wear it and won’t give it back. They discussed the story and made flow charts to show how the power shifted throughout the story and to use symbols to represent who had the power in each part of the story.

We noticed that this discussion was not as focused on power and that the kids seemed reluctant to share. We had reached the end of September and the social dynamics of being a fifth grader seemed to be kicking in. Students were more concerned with entertaining each other than in pushing their thinking. There was definite social drama going on as some of the boys were posturing for more powerful roles. A new boy in our class was getting a lot of attention from the girls. The girls wanted to play it cool in front of him and so we heard nothing from them that day in the discussion. This was not our best discussion; it was clear there was something going on with the girls in how they were positioning themselves as well as allowing themselves to be positioned by others.

Because we were concerned with how this social drama was going to translate into the work that day, we assigned partners to work on the flow charts. This worked out well, even though I don’t normally like to assign partners. The discussion wasn’t the best, but the flow charts were incredible. Many used symbols to represent the shifts in power along the continuum of the story. Danielle and Robbie created a flow chart that used bar graph symbols for each character to represent the shifts in power as the story unfolds. The key at the bottom of the chart shows the abbreviation on each bar to designate the character such as OG for older girl, YG for Yoon, and T for teacher (Figure 4). It was interesting to watch each pair of students talk about the ways in which power shifted from character to character throughout this story.

Students added to the class power chart before leaving the lab:

Dakota: Your power can change when someone has more power than you. Some people think they don’t have power, everyone has power.

Robbie: Sometimes you don’t realize how much power you have until someone with more power makes you realize it. Manipulation is one way people have power. Frustration makes you realize you have power. When other people are bossing you around, it makes you want to use power.

Danielle: It’s like the game Mousetrap, one thing sets off another, and then something else happens. Sometimes you don’t know you have power, then suddenly you have it.

In class, students read Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes (Coerr, 1977) in preparation for attending a field trip to the play performed by Pima Community College. In truth, I squeezed this novel into the curriculum at the last minute because I felt it would be a great way to prepare the students for this play. I’m so glad I did.

The play was a beautiful production and the cast and director were most impressed by the fact that our entire group (third through fifth grades) had read the book beforehand. The students all made strong connections to the character of Sadako. Our outing included a backstage tour and a question and answer period by the staff. During the Q and A, students from other schools asked questions about the costumes, how long it took to memorize lines, and how long the actors had been performing. Robert cut to the chase when he raised his hand and told the director how powerful the story was to him. He said the story was a clear message about how dangerous nuclear weapons were in wars. The director thanked him for his observation and we launched into a discussion of power while walking backstage.

Danielle told the director that there was a clear power shift in the story. She said at first the atom bomb had the power, then the leukemia had the power, but at the end Sadako held the power. It was clear that our kids were used to discussing issues. He looked at me and said, “What are you teaching these kids at Van Horne?” I told him we were looking at the big idea of power. He was clearly stunned at the students’ ability to conceptualize the issues and themes in the story and, shaking his head, asked what other books we were reading. The kids started calling off the titles of the literature circle books we had just finished, The Diary of Ma Yan, Red Scarf Girl, Chu Ju’s House and others. He didn’t know any of the titles, but found it interesting that we were focused on books outside the United States and wanted to know the titles of plays we might be interested in seeing in the future. It was a great experience for the kids, because they were able to make conceptual connections to what they had read at school and in the visual interpretation of the book on stage. I felt so proud of this group of smart fifth graders.

When we got back to school, I finished reading Hiroshima, by Lawrence Yep (1996), a short chapter book about the Enola Gay, the B29 that delivered the bombs to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I wanted the students to hear the other side of the story, a different perspective. As I read the step-by-step description of what the pilots were doing as they were readying and executing their mission, the kids were thinking of Sadako and her family on the ground in Hiroshima.

In their discussion it was clear that students felt ashamed of what Americans had done to the families of Hiroshima. They knew of the great losses we had suffered at the hands of the Japanese at Pearl Harbor but did not make the connection between Pearl Harbor and the dropping of the atom bomb. The cause and effect of these events was not part of their background knowledge. Even after talking about Pearl Harbor, the students only thought of Sadako because of the strong connections they had made to her character. Jose asked me, “Mrs. Edwards, when they dropped the bomb on Hiroshima, did they know that Sadako was down there?” I was so choked up, I almost couldn’t answer. I told him that as human beings, they were probably trying not to think about it, but as soldiers they were trying to carry out their mission successfully and that they knew there would be lots of civilians killed. The power this character had over my students was striking.

At the beginning of October, we moved from personal power to broader issues of power in other people’s lives. At this point in the year, I noticed social positioning and some shifts in roles, particularly in attitudes that resembled nonchalance and the emergence of definite leaders. Lisa read Rebel! (Baillie, 1994), a picture book set in Burma about a military leader who marches into a school to announce he is taking over. He is challenged in an unconventional way by a student who is brave enough to rebel. The object of power is a single student who anonymously removes her thong (sandal) and throws it at the general. In an effort to hide the identity of the “rebel,” all the students and teachers take off their thongs and throw them in a pile so the general can not determine who is missing their thong. We wanted to show the students that sometimes power can come from an unpredictable source and to show the power of a group of people who normally are perceived as powerless. The students in my class immediately started to twitter about the word “thong,” which they interpreted as underwear, and completely lost attention to the rest of the details in the story. Being fifth graders, and given their propensity for any opportunities for fun, the discussion took a strange turn.

In the group discussion it was obvious the students didn’t understand the story and wondered why the students threw underwear at the general. Bloome & Katz, (1997) state that people come together to accomplish something. Usually they have an idea about what that something is, however, the explicit purpose may not necessarily be what gets accomplished. The participant social relationships both influence and are influenced by the social action people take and by what is socially accomplished. It was apparent that this was happening here. The students had transformed the purpose into something different than what we had intended.

When asked what they thought of the book, they said it was very interesting, but no one caught who did it. They weren’t sure what went on. They said they needed a second book to find out. They wondered if the thong was thrown on purpose or accidentally. When Lisa mentioned that the children took off their thongs and put them in a pile, the students giggled. They wondered if the thong was thrown by one of the soldiers. Finally someone said they thought it was on purpose and was thrown by a kid. A debate followed.

According to Bloome and Katz (1997), people attempt to socially position themselves in particular ways, but that at the same time others are also socially positioning them. One student who was a poor reader was very outspoken during the discussion, even though it was evident he didn’t understand the story. He was not discouraged by redirection from the teacher or the other students. He was trying to show his dominance in our class and himself as a leader of the group. He was attempting to socially position himself as a leader in this situation. He felt like the discussion forum was the place to do this because, even though his reading skills were poor, he was comfortable with his verbal skills. Also within the classroom he was respected due to his size and athletic ability. His desire to have fun throughout the day was also admired by many of the boys. Many of his comments lead the group in the wrong direction and they silenced the girls who clearly didn’t want to appear to agree or disagree with him.

Initially I wondered why such a straightforward story would confuse students, both in the details and the big ideas. Once I realized why the students were distracted, I revisited the book later during a class read aloud to see if they could do a better job of understanding the concepts of power.

For this lab period, the students went to the tables to do wide reading of picture books about power and then returned to the story floor for a whole group discussion. Some of the books included in this text set were Night Golf (Miller, 1999), 17 Things I’m Not Allowed to do Anymore (Offill, 2006), My Secret Bully (Ludwig, 2005), and Always With You (Zee, 2008).

Concepts they discussed from these readings were:

• One kind of power is talent.

• You can lose power if you use it in a bad way.

• There is power in choosing your own friends and standing up to others who aren’t.

• Soldiers have power over people.

• There is power in love, trust, and memory.

After a second lab period of wide reading they found:

• Power is courage to follow your dreams.

• Courage is power to make friends.

• Bossing people around is forced power.

• Some people think they have more power than they do.

• Racism is an issue of power.

• People are afraid of losing power when they share.

• Some people have power they don’t know about.

• Emotions hold power.

The discussions for the next several weeks were inpacted by the social practices and positioning that continued to develop in our class. It was a bit of a concern as a teacher to see the girls, who I knew had so much to contribute be silenced by several vocal boys. I also knew that some of the voices were dominating and not leaving room for others or leading the discussion in nonproductive directions. This social drama was surfacing in classroom discussions as well.

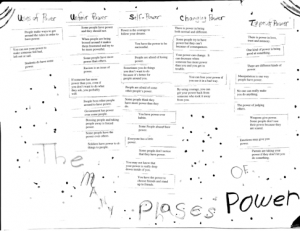

The following week in lab, our goal was to compare, contrast, and categorize our many ideas about power to organize our thinking. Lisa asked students to use their brains to categorize the ideas. They reviewed our class chart about what students had noticed about power each week. Lisa had typed up the ideas so that students could cut the sentences into strips and easily sort them. To help them understand sorting, Lisa used name tags and asked students for ideas on different ways to sort or categorize them, such as the different ways the name tags were written — color, size, font, number of letters, vowels, etc. She told them they would be sorting the statements by their meaning about power.

Students were asked to:

1. Read the list together at the tables.

2. Cut the sentences into strips.

3. Sort the ideas about power into categories.

4. Have an adult check to make sure they made sense.

5. Glue them onto the chart, and create labels for the categories. (*Must have more than three statements in a category, but no more than seven.)

6. Think together and read aloud.

There were major differences in the way the student groups worked. Some groups thought and worked together, while others had one person who took over and organized the task by giving directions. As the students sorted and created categories, we were surprised by the range of their thinking. As adults checked the categories, students talked about why they chose to group the statements in particular ways. They were able to justify their answers without hesitation, often through dialogue with each other.

Harste says that we outgrow our current selves through dialogue (Short & Harste, 1996). These students went beyond their current understandings of power and knew they were coming to new understandings. It was apparent that they were thinking conceptually about big ideas. They worked at a feverish pitch to finish their categorizing, engaging in negotiation and intense talk about power with each other. They barely finished, working frantically at the end. It was a giant “Aha!” moment for many students and the adults in the room as well.

Our study of power was meaningful to the students. I don’t think they believed they could make new discoveries about a subject they clearly knew so much about already. Lewis (1998) states that a social organization exists in all classrooms that privileges certain social and interpretive ways of being over others. What was evident was that for this work the social drama was put aside as these groups worked as a team. They were completely absorbed in the process, and were not worried about looking cool or the fact that they were the big kids on campus. It was amazing to see them so involved in this process and it was obviously important for them to engage with a lot of thought and creativity. They lost themselves in the ideas and in the excitement of pushing their thinking and forgot just for a moment they were fifth graders who did not want to appear to like school. They were able to engage as equal members of a team in a community of learners and thinkers.

Professional References

Bloom, D. & Katz, L. (1997). Literacy as social practice and classroom chronotopes, Reading and Writing Quarterly, 13(3), 205-226.

Lewis, C. (1998). Literary interpretation as a social act. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 42(3), 168-177.

Lewis, C. (2001). Literary practices as social acts. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Short, K. (2008). Exploring a curriculum that is international. WOW Stories, 1(2), http://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi2/?page=5

Short, K. & Harste, J. (1996). Creating classrooms for authors and inquirers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Children’s Literature References

Baillie, A. (1994). Rebel! Ill. D. Wu. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Coerr, E. (1977). Sadako and the thousand paper cranes. New York: Bantam.

Egan, T. (2007). The pink refrigerator. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Jiang, J. (1997). Red scarf girl: A memoir of the cultural revolution. New York: HarperCollins.

Little, J. (1986). Hey world, here I am! Ill. S. Truesdell. Toronto: Kids Can Press.

Ludwig T. (2005). My secret bully. Ill. A. Marble. New York: Tricycle Press.

Miller, W. (1999). Night golf. Ill. C. Lucas. New York: Lee & Low.

Offill, J. (2006). 17 things I’m not allowed to do anymore. Ill. N. Carpenter. New York: Schwartz & Wade.

Recorvits, H. (2008). Yoon and the jade bracelet. Ill. G. Swiatkowska. New York: Frances Foster.

Shea, B. (2008). Big plans. Ill. L. Smith. New York: Hyperion.

Wild, M. (2001). Fox. Ill. R. Brooks. La Jolla, CA: Kane/Miller.

Yan, M. (2002). The Diary of Ma Yan: The struggles and hopes of a Chinese schoolgirl. New York: HarperCollins.

Yep, L. (1996). Hiroshima. New York: Scholastic.

Zee, R. (2008). Always with you. Ill. R. Himler. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

WOW Stories, Volume I, Issue 3 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi3/.

One thought on “WOW Stories: Connections from the Classroom”

Comments are closed.