Cross-Cultural Understanding through Children’s Literature

By Melanie Bradley and Zeinab Mohamed

This vignette describes explorations with students that arose from a literacy community based in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. Please see Literature about Immigration and Middle Eastern Cultures by Seemi Aziz for an overview of this literacy community’s work.

I teach first grade in a diverse school with students from over 50 counties. While this is a rarity in rural/suburban Oklahoma, campus housing for the local university is within the elementary school boundaries, which provides an ethnically diverse population of students. During our time of reading and exploring books representing Middle Eastern and Arab cultures, Zeinab Mohamed worked in my classroom facilitating the audio and visual recordings. She also worked with small groups using comprehension strategies with the texts while I was responsible for mediating the whole group experiences. Because I teach in an early primary classroom, the book experiences included an initial read aloud. We came to the carpet and I read aloud while students participated in brief conversations about the text. After initial readings, the children worked as partners or groups to participate in book talks. Zeinab and I would both work our way from group to group to take notes on student conversation about the text. During the book talks, the students were instructed to create a record of their conversations and thinking, which provided us with work samples as well as material for reflection and evaluation. Zeinab and I worked together to reflect on our teaching experiences and plan future book experiences. Based on what we observed during the small group book talks, we then decided whether a book needed further investigation, what texts to use next in the study, and what we should contribute to conversation.

In October, we read Who Belongs Here? An American Story by Margy Burns Knight (1993) and Aekyung’s Dream by Min Paek (1988), and participated in interactive activities to create a two-week social studies unit about American immigration. This unit coincidentally laid a foundation for students as they began to explore books about Middle Eastern and Arab cultures. In this immigration unit, the students gained an understanding of what it would feel like to be an American immigrant in modern society and in previous eras. They built awareness of the struggles and difficulties of immigrant peoples. Some of the activities included looking into our family heritage and discussing family traditions that have been passed down through generations, creating a cultural quilt square to represent ourselves in a class quilt, going through a virtual immigrant tour on www.tenement.org, and creating suitcase collages of what we would want to bring to another country, as well as participating in book experiences and discussing characters’ feelings as immigrants.

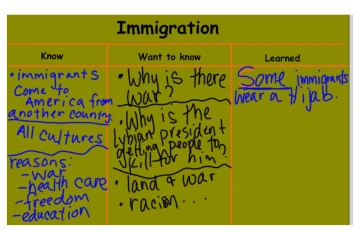

We began to use books representing Middle Eastern and Arab cultures for this unit in March. This provided an opportunity to assess the information the students retained about immigration after five months. Before reading the first book in this unit, My Name is Sangoel by Karen Lynn Williams (2009), the class filled out a K-W-L chart with what we knew about immigration from our previous book experiences.

As we reflected on the chart, Zeinab and I were pleased with the students’ ability to remember the content from the previous unit. We evaluated that they had ample background knowledge, even as first graders, to participate in book talks. Without explicitly explaining why people immigrate to other countries, the children were able to deduce four concrete reasons. Due to time constraints Zeinab and I were not able to return to the K-W-L chart after completing the unit, however, the students’ comprehension was evident in their work samples. Nevertheless, we were curious about what would have been discussed had we brought up this specific chart to draw conclusions from this learning experience.

We also sent home a survey asking parents to share the meaning of their child’s name, its origin, and why they selected it for the child. This is because the main character in My Name Is Sangoel deals with Americans struggling to accurately pronounce his name, a key part of his cultural identity. We decided to use this opportunity to celebrate our own cultural identities. When reading the book aloud to the class, we opened the book and showed the cover illustration and asked where they thought the boy in the illustration was from. They thought he was from America, because he was playing soccer. While reading, we discussed new vocabulary that came along in the story, such as refugee, “sky-boat,” the “moving stairs in an airport,”and the “doors that open magically when a person walks by” (Williams, 2009). We asked them to think about why Sangoel did not know the correct names for these things. The students immediately knew that his lack of knowledge came from living in a refugee camp where these items were not available. We also asked the students to talk with their neighbors during the read aloud about how Sangoel was feeling at particular times throughout the book. The students responded by sympathizing with Sangoel, though we wished they would have taken it a bit further. When asked what they would have done if they were in his shoes, most of the students originally said they would change their name to something easier to pronounce. Though Zeinab and I tried to keep our opinions out of the discussions, we decided to take the opportunity to discuss the emotional attachments that many people have to their given name. After a discussion, students changed their opinion to reflect the idea of maintaining their heritage through their name, if they felt it had cultural significance.

After reading about how Sangoel represented his name as a sun and a soccer goal, the students thought about their own names and created a pictorial representation of their names. I modeled this by making “melon + knee = MELANIE” for my own first name. While some students had difficulty, they all shared in the experience and celebrated their names and heritage as they shared their homework sheets about the origins of their names.

We lead the class in a discussion and oral summary of the story, probing their comprehension with questions such as:

- How do you welcome new students into this class?

- Do you think new students at our school feel discriminated against?

- Has anyone ever mispronounced your name?

- Would you ever change your name to fit into a new culture?

Zeinab and I were impressed by the students’ ability to retain the information from the previous lesson. They were familiar with the key vocabulary that had been introduced. The students discussed the elements of the story, identifying the main characters and listing information they gleaned about the characters. They recalled the country the characters were from, how they felt, and specific things they might have said in the story. They chose to fill in a story map about three main characters, Sangoel, his father, and his sister Lili. When thinking about the setting of the story, the students remembered that the story transitioned from Sudan to America, and compared the two settings. They described Sudan as a war zone that was dangerous and America as a safe place. They did, however, mention that Sangoel missed Sudan even though it was dangerous, because he felt at home there. They understood his feelings as natural, which demonstrated their development in comprehension. When reflecting in groups, we continuously heard comments about how students would have felt in his shoes.

The next book we read was One Green Apple by Eve Bunting (2006). We began by reviewing the K-W-L chart and then looked at the cover of the book to make connections and predictions about the book. One student said that “Ms. Mohamed has the same things, but her’s is blue and white.” Although the student did not know that the ‘thing’ was called a hijab, I asked where they thought that the girl was from based on seeing her wear a hijab. Students responded by saying South America, Egypt, Sudan, Libya, Africa, and Iraq, which was a surprisingly high number of countries. We frequently refer to the world map in class when a country or specific geographic region is named. For example, if a story mentions a family who takes a trip to the Euphrates River, I show where this is on the map in order to help students have a better understanding of the text. We had previously discussed that all Islamic countries are not on one specific continent. When a student mentioned Iraq, we asked what continent that was on, and they remembered that it was a part of Asia and not Africa, like many of the other Arabic speaking countries.

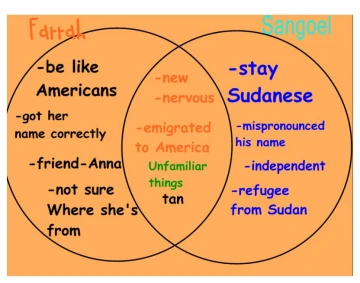

While reading the story, we stopped periodically for discussion as the main character, Farrah, expresses her feelings of being in a new country. We compared her feelings to that of other characters we have been introduced to. One Green Apple focuses on the idea of a cultural melting pot in America, while My Name is Sangoel looks at America as a “stir-fry” of different types of cultural uniqueness existing together. The students were unable to see or connect to this concept, so Zeinab and I left it alone realizing that further investigation would depend on our “teaching” the concepts, rather than emerging from the students’ dialogues and interpretations of the text. In the book, Farrah calls attention to the idea that even though a green apple is different in color, when made into cider with red apples, it is no longer individual, but becomes one with the others. My students, because of their background reading of characters who wish to maintain their cultural identity, like in My Name is Sangoel and Aekyung’s Dream, looked at the green apple as this representation. When creating a Venn diagram comparing the two characters, they focused on how the characters were treated, who their friends were, where they were from and so on. The overwhelming concept is the differences of a melting pot and a stir-fry America. We wondered if they would have understood a melting pot society had we begun with this book and not had so much discussion around the concept of stir fry.

When Farrah calls her head covering a dupatta, Zeinab and I asked how this compares to other books we read. The students saw that this character is probably from a different country, since she has a different term for a head covering/ We asked the students “What is a dupatta?” and they did not know. We informed them that it was the head covering, and we compared the way it looks to the hijab. The students then deduced that Farrah is probably not from Sudan, as Sudanese people, like those in My Name is Sangoel, wear the hijab. They did not retain the term dupatta, however, but reverted back to hijab when continuing the discussion of One Green Apple. After informing the students of the differences in head coverings, we did not correct them, because it seemed to defeat our purpose for investigating what they take from the text rather than what we teach. Since they were holding onto the term hijab, we allowed them that freedom, as they were not ready to distinguish between the two terms.

Also, when we were discussing the two books, students recalled the unfamiliar elements that Sangoel came across in America, and connected them to Farrah’s similar struggles. Sangoel was introduced to an escalator, an airplane, and automatic glass doors. Farrah was introduced to a juicer in the apple orchard. In both books, the immigrants describe the items through a sensory experience of the unknown object while we, as readers, were able to make the terminology connection.

After reading the story and comparing the two characters, we decided to bridge the stories into our writing curriculum. At the time we were working with biographies and autobiographies, so we decided to have the students write the autobiography of one of the characters. They engaged in role play and wrote from that character’s point of view. We divided the class into two groups and assigned one group to Sangoel and the other to Farrah. Zeinab and I reviewed the types of things we included in our autobiographies, and students recalled including their name, family member’s names, age, favorite things, and interests. They searched in the books for information to write in the character’s autobiographies. Bunting does not mention Farrah’s age in One Green Apple, so the children decided to make a prediction. We looked at the cover, and together they agreed that she was probably in 6th or 7th grade, so we labeled her as 13. The students then looked back through the book to find significant information to include in an autobiography to write as a group. We were quite impressed with the connections they made from their previous experience writing their own autobiographies, and the ones they worked together to create for the character’s in the stories. They related to the character Sangoel’s emotions writing, “I feel sad when people mispronounce my name”. We were also impressed to see the retention of the vocabulary used throughout the lessons, such as, refugee, immigrated, Pakistan, Sudan, and America. All of these terms were used in the autobiographies.

The next text we read was Big Red Lollipop by Rukhsana Khan (2010). The students’ reactions and discussion of the book focused mainly on the interactions among the siblings. They did not pay attention to the cultural bias of the Pakistani mother who was naïve about American customs. The candy that was stolen was a major focus, and the students made many text-to-self connections about similar situations with their younger brothers and sisters. The students did raise the issue that the children in the book called their mother “Ami” rather than mom. They were able to predict that the family was from a country other than America and spoke another language, based on the use of this term. Most of the students predicted that the sister would try to get revenge for the loss of her lollipop, rather than do the honorable thing and stand up for her sister. When reflecting on the lesson, Zeinab and I decided this was due to the age and maturity level of our students. One student, however, connected to the act of kindness Rubina showed in standing up for her sister. Others agreed that having integrity, which was a word the class studied, would allow you to demonstrate understanding and compassion for your sibling, and not want them to have the same hardships as you did. One student said “she didn’t want her sister to have to go through what she had been through.” Again, the main ideas taken from the text were the conflicts between the family members and not the cultural aspects of the text.

The final book was Mirror by Jeannie Baker (2010). In our discussion the students compared the lack of cars on the Australian side of the book and the color of the characters’ skin. They noticed that one side had “outside stores” and the other had “inside stores.” When looking at the market in Morocco, they made text-to-world connections with a farmer’s market, as well as the pictures I had previously shown them from my trip to a Belizean market. They noticed that only Australia had electronics, buildings and roads. We were very impressed with these observations. The students discussed what a magic carpet is. They knew that it was a carpet that flies, but noted that “they’re not real.” The students discussed that magic carpets were fantasy, because “there is no such thing as magic.” When we asked them how they knew what a magic carpet is, they agreed that they were from the Disney movie Aladdin, and were not real. When comparing the cultures of the two sides of the “Mirror”, they referred to the different settings in the book as “us” and “them”. They automatically looked at the light skinned and modern world of Australia to be America, and the desert-like illustrations of Morocco to be “them.”

After reading, we worked with our think sheets to record our thoughts. I have students fill these out when we read new stories to practice recording their thinking. Then, we go back and discuss the various things that were recorded. Students make inferences as well as observations, or even their reaction to a particular text. One student recorded that “In Morocco, when they go to the store, it is outside.” This indicated to us that the representation of Morocco in the text is misleading to child readers, as there was no inclusion of urban Morocco Another recorded that “In Morocco they ride camels to work.” We found that we needed to expose them to more literature about Morocco and Australia as well, in order to help them make more accurate observations about the regions.

Due to the students’ assumption that the modern setting in the book was America we informed them that it was not the U.S. and showed a slide show of images from Morocco and Australia. The slide show included images of the Australian outback as well as urban Morocco. Once the students saw that the book only portrayed one side of these countries, they decided that the book was not accurate, and talked about what they would change to make it more authentic. They were able to write and illustrate changes they would make to the story. Using the observations from their think sheets and the slide show, the students discussed and represented an overwhelming misconception in the text. Many students discussed the skin color, the lack of “big buildings in Morocco” and “adding the Outback in Australia.” We were very pleased with these connections.

We know that the overall book experiences benefited the students. They were able to comprehend the text and participate in literature circles with their peers. After engaging in the book talks in both units, they became more empathetic and accepting of others, especially those immigrating to America. Their awareness of common misconceptions in literature grew as well, and they become more familiar with various world countries and populations. They understood why people immigrate to other countries and what it feels like to do so.

Although it was difficult, especially at first, to let go of the “teaching” of these books, Zeinab and I have learned to let go of the teaching a bit more, even in the beginning. We originally worried that the children would not be able to benefit fully from the book without guidance toward the elements we wanted them to comprehend. We now know the importance of allowing students to make their own meaning of the books and incorporate the new knowledge into their own experiences with books and the world around them. In the future, we want to allow some concepts to go “over their heads” if they do not seem ready to make sense of them. We noted that they did not retain the information introduced to them when they were not ready to hear it anyway, so it was not effective to introduce them to concepts too early. We have learned that it is not about understanding every element and underlying theme in a story, but creating some kind of meaning from the story.

Throughout the process we continually reflected on how easily the children owned the new vocabulary. Frequently they were using terminology that we had anticipated would take longer for them to understand and remember. There was also less cultural bias and stereotypes than we had anticipated. At this young of an age there are unfamiliar concepts like the hijab and dupatta, that are not yet associated with negative thoughts of the people wearing them. They are more curious and open-minded when introduced to these new ideas.

Conducting the literature circles demonstrated that students can engage in critical literacy at any age. The way in which they interact with multicultural literature needs to be adjusted for their emotional preparedness and maturity. For this reason, we did not address politics or religion, but stayed on the topics of tolerance and compassion for people from other cultures and perspectives. We also wanted to make the focal point to be pride in ancestry, which was definitely a success. All of the students felt proud of their cultural backgrounds and gained appreciation of others.

References

Baker, J. (2010). Mirror. Somerville, MA: Candlewick.

Bunting, E. (2006). One green apple. New York: Clarion.

Khan, R. (2010). Big red lollipop. New York: Viking.

Knight, M.B. (1993). Who belongs here? An American story. Gardinder, ME: Tilbury House.

Paek, M. (1988). Aekyung's dream. San Francisco, CA: Children's Book Press.

Williams, K.L. (2009). My name is Sangoel. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdman.

Melanie Bradley teaches first grade in Stillwater Oklahoma. She is currently working on her Master's degree in reading and literacy at Oklahoma State University.

Zeinab Mohamed graduated with a Bachelor Degree in Elementary Education from Oklahoma State University in 2009. She is currently a third grade teacher at Will Rogers Elementary School in Stillwater, Oklahoma and a graduate student in the Reading/Literacy Master’s degree program at Oklahoma State University.

WOW Stories, Volume IV, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesiv1.