Learning About Identity in Kindergarten/First Grade through a Global Literature Lens

By Lacey Elisea and Christy Reller

At the beginning of the 2019-2020 school year our Kindergarten/1st grade class at Creation School began a journey into reading and learning with global literature. We wanted students to explore their own identities and develop an understanding of different cultural perspectives. "Global literature also creates opportunities for children to explore outside their life experiences in order to understand, respect and value diversity and to create new experiences from which they can draw upon in the future" (Acevedo, Pangle, Kleker, & Short, 2017, p. 24). Our class was culturally diverse (primarily European American but also Latinx and Brazilian) and consisted of nine students, six girls and three boys; five first-graders and four kindergarteners. Students resided in two-parent homes where English was the primary language spoken. Creation School is an early learning school with classes for students from two-years-old to first grade. We, Christy Reller and Lacey Elisea, were co-teachers in the Kindergarten/1st grade classroom.

Creation School is located in Vail, Arizona, a suburb of Tucson, 68 miles from the United States/Mexico border. The school offers a unique educational experience for students with its rural location in the Sonoran Desert. This allows the teachers to integrate many outside authentic experiences into the curriculum. Our goal this year was to integrate global literature across content areas as much as we could. The main time for this, though, was during Storying Studio, three times a week for one hour.

In this vignette, we describe our cross-cultural study of Mexico and how we contextualized it within a global perspective to integrate into our curriculum. To understand other cultures, though, it's important to first understand ourselves as cultural beings. We begin by sharing our study of personal cultural identities, including our Sonoran Desert environment, before discussing our Mexico study.

Learning About Ourselves

Our journey with global literature began by inviting students to explore their personal cultural identities to help them know and understand themselves as cultural beings. Global literature offers students opportunities to broaden and enhance their perspectives of themselves and others (Acevedo et al., 2017).

Learning Where We're From

One of the first books we read to explore cultural identity was My Name is Sangoel (Williams, Mohammed, & Stock, 2009). In this story, Sangoel, a refugee, leaves his homeland of Sudan with his mother and sister and moves to the United States. Sangoel must make many adjustments to his new home and is concerned that people have difficulty pronouncing his Dinka name, which is very special and important to him. Eventually, Sangoel finds a way to help others remember his name.

To help our students think about the importance of their names and understand that in the past members of their families, like Sangoel's, immigrated to the United States, we had them find out where their families originated. When students shared that information, we located the place on a world map (see Figure 1). Together, we discovered that a majority of their ancestors came from Eastern European descent. Ella, for example, was from European descent and her mother was a Belgium citizen whose first language was Dutch. Emily's mother was from Brazil and Emily was learning to speak Portuguese. Our goal was for students to realize that who they are reaches beyond Vail, beyond Arizona, and beyond the United States. Realizing their families were similar to Sangoel's helped students begin to explore their identities, consider their own uniqueness, and think about themselves and their families more deeply.

World Map showing the students' family origins.

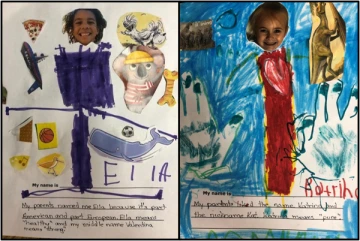

Exploring Our Names

We also used My Name is Sangoel to invite students to ask parents about the origins of their names. We added this information to a self-portrait they created by drawing a body on a photo of their heads, similar to art found on several pages in the book. Students surrounded their drawings with items they liked. Figure 2 shows two kindergarten examples. For her name, Ella (left) said, "My parents named me Ella because it's part American and part European. Ella means 'healthy' and my middle name Valentina means 'strong'." Around herself Ella drew and pasted pictures of pizza (her favorite food), dogs, a music note, an airplane, and a whale. Ella said she included the whale because she had recently been to the ocean and enjoys water. Katrina (right) said, "My parents like the name Katrina and the nickname Kat. Katrina means 'pure'." Katrina pasted pictures of cheetahs (her favorite animal) and dinosaurs around herself. She drew a big heart and said she has "lots of love in her heart." Each child shared the information about their names and why they chose the items around themselves.

Additional favorite books about identity were Marisol McDonald Doesn't Match (Brown & Palacios, 2011), Mary Wears What She Wants (Negley, 2019), and The Invisible Boy (Ludwig & Barton, 2013). These books encouraged students to think about who they were as cultural beings.

Creating Cultural X-Rays

Cultural awareness plays an important role in helping young children develop a positive sense of identity, build their own self-esteem, and understand that who they are is more than how they 'look' outwardly. It includes the kind of person they are. Since this is a difficult concept, we used cultural x-rays (Short, 2009) to help students understand. A cultural x-ray is a look at the layers of a person: what is seen on the outside and what is inside someone's heart. It consists of drawing/writing what is known about someone on the different layers. To begin, we worked together as a class to make several cultural x-rays for characters in books we read.

For example, in Marisol McDonald Doesn't Match, students noted she had red hair, brown skin, and liked to wear clothes that didn't match, such as polka dots and stripes, which we drew on a cultural x-ray of Marisol. Then we asked, "What can you tell me about Marisol that you cannot see?" Students replied, "Marisol wants to be herself, do what she wants, and wear what she wants, draw, play." And, "She loves family, Kitty, and friends". These we wrote in Marisol's heart.

After making several cultural x-rays together students created one of themselves. Logan's (kindergarten) cultural x-ray is found in Figure 3. Around the outside, Logan wrote "bike" and "Ryan" (brother) and drew a monkey (Ryan's favorite animal) and a soccer ball (his favorite sport). In his heart he wrote "family, God, and otters " for what he loves and values most.

Logan’s cultural x-ray showing what is visible about him on the outside and what matters most in his heart.

Through our focus on identity, students demonstrated deeper understandings of themselves. From there we moved into a study of Mexico.

Learning About Others: Our Cross-Cultural Study of Mexico

We transitioned from our study of identity to our cross-cultural study of Mexico with an exploration of the Sonoran Desert. All of us at Creation School live in the Sonoran Desert which makes it part of our identities and who we are. The Sonoran Desert is an area in the United States that extends into Mexico and includes many unique plants and species. We read and discussed books such as Desert Giant (Bash, 2002), Creatures of the Desert World (National Geographic Society, 1987), and The Seed and the Giant Saguaro (Ward & Ranger, 2003) to study the plants and animals. Students easily related to the landscape, plants, and animals since they'd actually seen many of the species, such as saguaro cacti, prickly pear cacti, coyotes, bobcats, and rattlesnakes.

Learning About Mexico

We began our study of Mexico by examining a map to see where and how we shared the Sonoran Desert. Since Vail is close to the Mexican border, many Mexican traditions and customs have blended into our own cultural fabric. The first book we read was Dear Primo: A Letter to My Cousin (Tonatiuh, 2010). In the story, an American boy writes to his cousin who lives in Mexico. Lacey speaks Spanish and talked about the language and read the Spanish text. Students began to see differences and similarities in the United States and Mexico, even though for us, many of the Mexico pages in the book were familiar, such as pinatas and traditional foods like tortillas. Students also connected with the story because the characters were around their age. McKenzie stated that she hoped to start writing to her cousin who lives in Mexico.

We included several other experiences in our study of Mexico. One was inviting students to explore a text set of nonfiction books over several days. The text set included books about Mexico that focused on topics such as geography, animals, customs, history, families, and rainforests. Students partnered together to read the text and examine the pictures. On sticky notes, they wrote or drew what they found interesting and then marked the page. After picking two or three interests, they presented their findings with their partners. Katie Wood Ray (2010) writes in her book, In Pictures and In Words, "getting their hands on actual books connects children to the study in a tangible, meaningful way, so much more than if the books stay safely tucked in a basket under the teacher's care" (p. 83). This interaction with nonfiction sparked many discussions about what students found interesting and why, and allowed us to know their interests to build on in subsequent weeks.

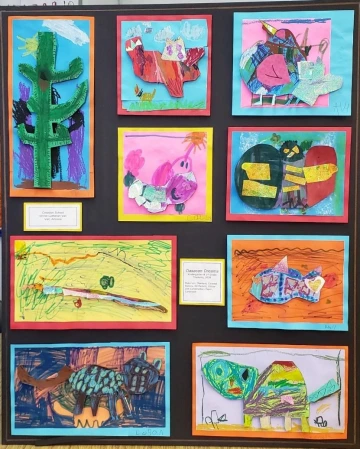

Our strong interest in art and illustrations lead to a study of Oaxacan art. Oaxacan art is an art form from an Indigenous culture in one of Mexico's southern states. Many bright colors and patterns are used in Oaxacan art. Oaxacan artists mostly use representations of animals but also have other figures. We introduced the focus on this art by reading Dream Carver (Cohn, 2002) and examining many Oaxacan (large and small) art pieces we brought from home. Students noticed the artists' different patterns, brush techniques, and bright colors and created their own figures by drawing/painting (see Figure 4). Katrina (kindergarten) kept referring back to the illustrations in Dream Carver as she worked on her animal. She used the book as a resource for her animal but said, "Mine is a cheetah not a jaguar like the book. But I like the design."

Reflecting on Our Learning

Oaxacan-style figures the kindergarten and first graders created.

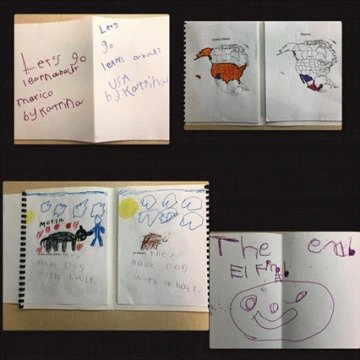

To pull our learning together and help students reflect on what they'd learned about Mexico, we invited them to create books. The books were comparisons of how life for us in the United States was similar to and different from life in Mexico. We knew that exploring cultural connections and differences would deepen students' intercultural understandings (Acevedo et al., 2017).

We began by having students look at the sticky notes they'd taken from the text set and think about their learning from other experiences. We then had them share U.S./México similarities and differences they noticed and listed these on a chart. The chart included the topics such as Independence Days, foods, animals, flags, celebrations, geography, and other comparisons.

Students choose from the chart what to write about and, over several days, created flip books with one side of the book on Mexico and the other side on the United States. The U.S. page began with "In the United States…" and the Mexico page with "En México…" Students completed each sentence starter and drew a picture to accompany their writing. They also decided on titles for the two sides of their books and made cover pages and end papers.

Katrina's titles, for example, were "Let's Go Learn About Mexico" and "Let's Go Learn About USA" (see Figure 5, upper left). The first page of each side was a North American map, where students colored the area for Mexico and the United States (see Figure 5, upper right). They also choose a different color for Arizona to show where they lived.

In Figure 5 (lower left) are Logan's (kindergarten) pages about dogs in the U.S. and Mexico. On the left he drew a picture and wrote, "In the United States have dogs with hair." On the right he drew and wrote, "En Mexico they have a dog with no hair" . When McKenzie completed her book she asked, "How do you say 'The End' in Spanish?" With assistance from Lacey, she wrote "The End" on the back-cover page in English and "El Fin" in Spanish (see Figure 5, lower right).

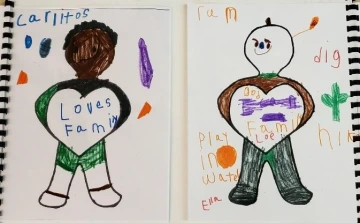

For the last pages of their books, students completed a cultural x-ray on themselves one day and on the following day, one for Carlitos, the character from Mexico in Dear Primo. Focusing on Carlitos made this more concrete and real for students in thinking about children living in Mexico. As a class, we discussed Carlitos and what we knew about him. Students identified things such as liking to swim and fly kites, enjoying Day of the Dead celebrations, and helping with his family's animals. Then we talked about what they thought mattered most to Carlitos and would be in his heart. From his interactions with others and letters to his cousin in the U.S., students suggested that Carlitos was kind and loved his family. They then independently created their own cultural x-rays for him.

As an example, the cultural x-rays Ella (kindergarten) created for Carlitos (left) and herself (right) are in Figure 6. She colored his skin and clothes and around the outside drew symbols for the things he liked. In Carlitos' heart Ella wrote 'Loves family' as what mattered to him. For herself she drew a small bun on top of her head (how she often wore her hair). She wrote on the outside that she likes to run, dig, hike, and play in water. In her heart she wrote Leo (her dog), dad and family.

Ella's cultural x-rays of Carlitos (left) and herself (right).

Emily's (first grade) cultural x-rays for herself (left) and Carlitos (right) are in Figure 7. Emily only wrote her family in her heart. She said, "You can tell I'm seven from looking at me" and placed a 7 on the outside. She also added Minecraft, Pokemon, cats, and art around the outside of herself. Together, the class had estimated that Carlitos was about eight years old so she wrote that and also included a kite, bike, a soccer ball on the outside. In Carlitos' heart, Emily wrote that he loves family and is good.

Emily’s cultural x-rays of herself (left) and Carlitos (right).

These cultural x-rays revealed their understandings of themselves and others. They saw that even though they looked different and liked different things outwardly, what mattered most to them in their hearts was similar. As Hazel Rochman (1993) says, "The best books break down borders. They surprise us - whether they are set close to home or abroad. They change our view of ourselves; they extend that phrase 'like me' to include what we thought was foreign and strange" (p. 9). Students started to see connections between themselves and others from a different time and place and to extend the concept of self and understand others.

Final Reflections

While our students are young, they developed understandings of their own and another culture and began to think more critically. They saw similarities and differences with other children through our studies with global literature and began to consider and respect perspectives beyond their own. This brought ideas and concepts that were foreign and strange to them into a new light and encouraged them to think and observe more deeply and critically. When an eighth-grade foreign exchange student from Korea visited our class, students asked high-level questions that pulled from prior knowledge. The exchange student showed them how to write their names in Korean. Emily said, "The letters are different." Derek noticed the difference in the letters and added that "Spanish sounds different but the letters are the same as English." Through their experiences with global literature students gained deeper knowledge of cultures and of themselves and others as cultural beings and grew in their intercultural understandings.

References

Acevedo, M., Pangle, L., Kleker, D., & Short, K. (2017). Engaging young children with global literature. The Dragon Lode, 35(2), 17-26.

Ray, K.W. (2010). In pictures and in words: Teaching the qualities of good writing through illustration study. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Rochman, H. (1993). Against borders: Promoting books for a multicultural world. Chicago, IL: American Library Association.

Short, K. (2009). Critically reading the word and the world: Building intercultural understanding through literature. Bookbird: A Journal of International Children's Literature, 47(2), 1-10.

Children's Literature References

Bash, B. (1989). Desert giant: The World of the Saguaro Cactus. San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club.

Brown, M., & Palacios, S. (2011). Marisol McDonald Doesn't Match/Marisol McDonald No Combina. New York: Children's Book Press.

Cohn, D., & Cordova, A. (2002). Dream Carver. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle.

Ludwig, T., & Barton, P. (2013). The Invisible Boy. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

National Geographic Society. (1987). Creatures of the Desert World. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society.

Negley, K. (2019). Mary Wears What She Wants. New York: HarperCollins.

Tonatiuh, D. (2010). Dear Primo: A Letter to My Cousin. New York: Abrams.

Ward, J., & Rangner, M. (2003). The Seed and the Giant Saguaro. Flagstaff, AZ: Rising Moon.

Williams, K., Mohammed, K., & Stock, C. (2009). My Name is Sangoel. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

Lacey Elisea teaches Kindergarten/First Grade at Creation School, Vail, Arizona.

Christy Reller has taught Kindergarten/First Grade at Creation School, Vail, Arizona.

© 2020 by Lacey Elisea and Christy Reller

WOW Stories, Volume VIII, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work by Lacey Elisea and Christy Reller at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/volume-viii-issue-1/4.

WOW stories: connections from the classroom

ISSN 2577-0551