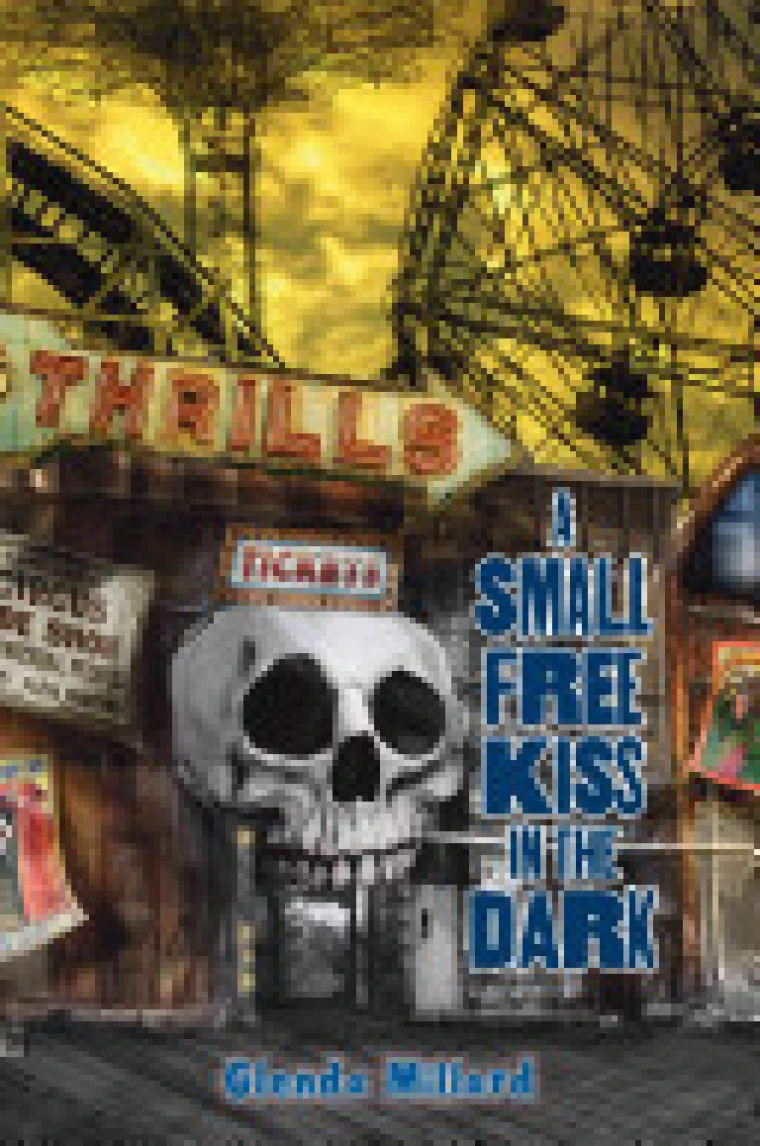

A Small Free Kiss in the Dark

Skip, an eleven-year-old runaway, becomes friends with Billy, a homeless man, and together they flee a war-torn Australian city with six-year-old Max and camp out at a seaside amusement park, where they are joined by Tia, a fifteen-year-old ballerina, and her baby.

ISBN:

9780823422647

Genre:

Fiction Realistic Fiction

Awards:

Awards

Region:

Australia